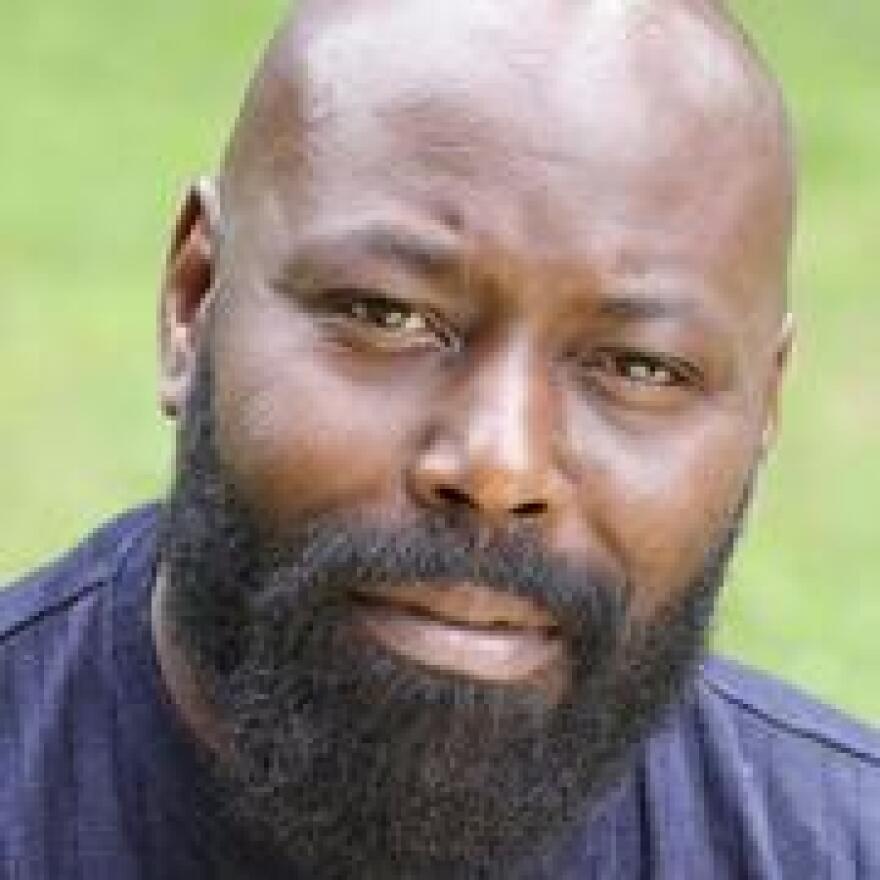

It was only last month that we could finally read the stories in the long-awaited collection “If I Had Two Wings” by Randall Kenan. On the heels of that came the shocking news of Randall Kenan’s death on August 28 at the age of 57.

In two previous books — the novel "A Visitation of Spirits" and the collection "Let the Dead Bury Their Dead" — he created the fictional town of Tims Creek, North Carolina. For the new collection, "If I Had Two Wings," we are back there again — as are some of his earlier characters from previous works.

These characters are immersed in unlikely situations made realistic by an inherent verisimilitude of this imagined space in the South and all the concomitant social, cultural and racial concerns Kenan treated so effectively.

In “When We All Get to Heaven,” Ed Phelps has accompanied his wife, Isaline, on a trip from Tims Creek to New York City. She’s attending the National Baptist Convention. This is the '80s, as we soon gather. Ed is exploring midtown and marveling at the sights and sounds, enjoying even crowds and the chaos and mostly reliving the joy of eating a $10 pastrami sandwich from the Carnegie Deli.

He’d been to New York City only once before on his way back from Korea. Then as now, he is not totally welcomed, even in this diverse metropolis where he is eyed warily as “he continued to make miration at the fruits and vegetables and flowers at a grocery stand.” He takes it in stride, as he has many other things he shares anecdotally, and he reflects and walks along the crowded streets.

Pretty soon, Ed is swept up by a throng gathered around a stretch limousine. The crowd is there for Billy Idol. I did say this was the '80s. Ed observes the small mayhem and chaos of what must be a rehearsal or soundcheck before a big show. With his spiky platinum hair and signature sneer, Billy Idol beckons Ed to come closer. He calls him “Deacon” and insists he play a song. Ed had not played a guitar in over 15 years but the “doorways in the back of his mind began to slowly open, then more and more, one by one, two by two, four by four, and he remembered his grandfather and how he played and how he taught Ed to play.”

Ed recalls the way “Mr. Moses Roscoe, who drove a truck, but was so good he played sometimes for money.” And then just “like a silverfish under a sink, a song jumped up into Ed Phelps’ head and he commenced to sing and play.” At listening to the impromptu number, Billy goes from “cat-eyed” to “all Christmas.” Later he says his good-byes and returns to the hotel.

Flipping through the channels of the television, Ed happens upon the “Dancing with Myself” video and decides that the celebrity “looked downright sick and pitiful. He looked like he needed to go home to his mama and get something good to eat.” He doesn’t even mention the encounter to his wife. As he nods off to sleep, Ed continues his journey on to the past, recalling his grandfather’s voice.

He won’t be changed by the experience and the only memories that will continue to haunt him are the ones that have always existed for a man such as Ed Phelps.

The past is what rises up to meet our present in the idiosyncratic moments of our lives when we might have a brush with a famous person who has nothing to offer us — not in any way not for any price.

We see this in “The Eternal Glory That Is Ham Hocks.” The narrator’s mother is invited to be a private chef to Howard Hughes. He’d been a young man when her mother cooked for the family. Hughes is so desperate to be able to enjoy those foods and flavors again that he goes to Tims Creek to track down the cook’s progeny.

The story within this story is the one that has the narrator’s grandmother, Inez Cross Picket, even going to Houston, Texas. The narrator says, “How my grandmother — whom I never met — a young African-American woman born in a teeny NC town in 1892, found herself in Houston, Texas in the 1920s, I’ve yet to discover.”

Hughes will pay any price to be able to taste food like Ms. Picket’s again, but her daughter will not cave to the high-dollar offers from Howard Hughes. As the number goes up, it’s almost impossible to imagine how she could turn down the money.

This is a story not to be read on an empty stomach. As we read the descriptions of the fare enjoyed by the Hughes father and son, we will understand the millionaire’s compulsion, "this mania — one among the many he collected and harbored.” But the narrator surmises that all of this has nothing to do with the food. “In the end,” he says, “it was about time, time lost, time gone, about remembrance, about a feeling.”

Kenan’s life as a gay man was reflected in his books, including in this new collection. The complicated intersection of gay life and the traditions of the rural South figure in, for example, “I thought I Heard the Shuffle of Angels’ Feet.” Protagonist Cicero is back home in North Carolina to see his Uncle Dax in the nursing home. Cicero is out as a gay man. He has lost his partner to AIDS. As he interacts with high school friends and his only close relations, we feel the tensions that hasn’t managed to elude, even after all these years.

A lot has happened since he was last on the high school football team struggling with his identity and his sexuality. Now he looks askance and how the town keeps going. Cicero decides that “Time was not a winged chariot. It was a space shuttle. A battlestar. A comet.”

TPR was founded by and is supported by our community. If you value our commitment to the highest standards of responsible journalism and are able to do so, please consider making your gift of support today.