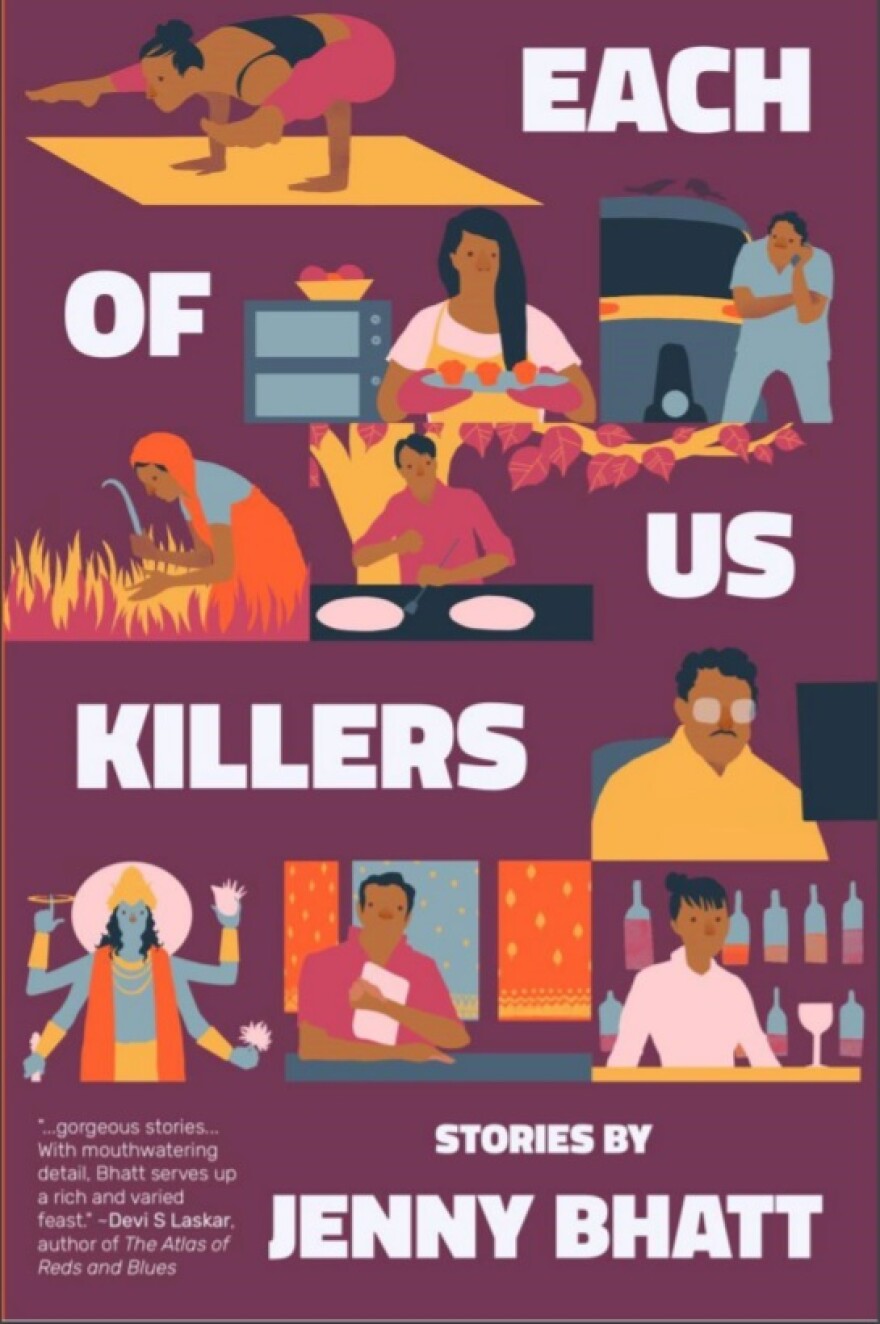

Fifteen stories make up the debut collection by Jenny Bhatt, and each story is as different from the next as it can be, featuring diverse settings, characters, and conflicts. Points of view vary as well. Flash fiction pieces are interspersed here among the much longer stories, but you’ll luxuriate for as long in a story that spans a couple of pages and be haunted by its lingering lessons.

For as richly diverse as the collection is, the stories have a lot in common, too. An undeniable element of every story is that everyone works. Everyone is defined in one way or another by a career they’re enduring or one they are born into or born to do, guided along by the limitations imposed by society or expectation but also by the barriers the characters sometimes impose on themselves.

The stories set in the United States and England include characters who are Indian immigrants, whose luck can be addressed only insofar as the opportunities they created for themselves but must then face the inherent conflicts an immigrant faces, regardless of their newly appropriated status in the new country.

In the first story, “Return to India,” set in Texas, we meet an immigrant character and learn about him only through the interrogations by police of his co-workers. The man, Dhanesh Patel, an engineer, has died. What we learn of him comes by way of the information and glimmers of dubious insight offered by his co-workers, each of whom in short dramatic monologues ends up revealing a measure of unreliability that says far more about them and their assumptions and biases than about Dhanesh. One co-worker generalizes what “Hindu men” are apt to do to keep “their women in line.” Another offhandedly surmises that Dhanesh just “never really took” to his co-workers and assumes he was frustrated when he was passed over for a promotion. Colleague after colleague is questioned. It is only Dhanesh who does not have a voice to defend himself or correct the record for himself, but we soon discover that in life, he was also as bereft of such control.

Such is the life of many characters. If all stories are about loss and if that is where the element of conflict emerges in a story, then in Jenny Bhatt’s stories the central loss seems to come from how living in a particular place infringes on our lives — because of some disparity, some lack of equity. Many of the characters acknowledge this void and still choose to fill their lives meaningfully. One such story is “Life Spring.” The protagonist has divorced her husband, Manish, and returned to Mumbai to make her life. She sells baked goods — a job she obviously loves and is very good at — but something is still missing, a secret ingredient. The small attentions of a delivery person make her return to the woman she could have been had she not ever married, a woman chasing her passion all along and laboring persistently to be able to move her business from her own small apartment to a new dedicated property. Again, work is the connective tissue within and between stories.

The enigmatic title of the book might suggest violence. And there are kinds of assaults here, the slaps in the face and punches in the gut — the visceral reactions to life’s quieter disappointments and traumas that come through everything from power struggles to unrequited love to, yes, the actions and inactions that contribute to quick death or a slow and painful passing.

The story “The Waiting” is told from the point of view of a dead woman whose husband is so overcome by her death that he slowly loses his grip on reality. We know she has died and she guides us through the process of his own turning away from a life he cannot face without her.

“Mango Season” is one of the most gorgeous stories in the collection. It is a quick education in mangos, to be sure, but it’s context is made all the richer by the more specific setting of the shop where protagonist Rafi works selling saris to young college girls who “giggle at his every flourish” or where a “mother and daughter shopping for wedding” make him “unfold and refold every sari they had discarded earlier.” The inconsequential workday takes a turn when one patron demands a very specific sari — an elaborate and expensive one in her favorite pink color “with zardozi” and a “velvet backless choli” to set off a large gold necklace.

Rafi imagines the party where the woman, looking like her own dazzling favorite film star, would wow the guests. It is the stuff of dreams. But having succeeded in selling her the sari, Rafi attains a certain sense of satisfaction. The small transaction is enough for him to understand “the joy of simply being alive in a world filled with undiscovered possibilities,” where he can still recall his mother smelling of cloves, reciting the verses that meant so much to her and how the simple pleasure of eating a ripe mango recalls the “exquisite hopes of youth” even decades hence when the woman in the pink sari herself has grown old.

Each of Us Killers is Jenny Bhatt’s debut book but you will feel that you have encountered this level of skill, craft, and complexity before in reading the masters of the short story genre — even while the author subverts what we so often encounter in the genre about notions of loss and lonely voices and who gets to tell their own stories.

Yvette Benavides can be reached at bookpublic@tpr.org.

TPR was founded by and is supported by our community. If you value our commitment to the highest standards of responsible journalism and are able to do so, please consider making your gift of support today.