Get TPR's best stories of the day and a jump start to the weekend with the 321 Newsletter — straight to your inbox every day. Sign up for it here.

Throughout November, TPR has presented "Native American Moments," a special series exploring both well-known and little known stories of indigenous people, descendants of Native Americans, and the policies that influenced the evolution of the United States.

The project was produced in collaboration with the American Indians of Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions.

This special report collects and expands on all those stories.

Ramón Vásquez y Sánchez

Ramón Vásquez y Sánchez was an indigenous leader, artist, activist, and cultural historian from San Antonio.

He was born in 1940 to the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation, and by age 10 he was studying visual arts.

Vásquez y Sánchez fought discrimination and celebrated Texas indigenous culture. His visual work helped humanize Native American history through art.

During the 1970s, Vásquez y Sánchez combined art with grassroots activism.

He was a leader of the Chicano civil rights movement and a founding member of La Raza Unida Party.

Vásquez y Sánchez also co-founded two nonprofit organizations: Centro Cultural Aztlan and American Indians in Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions.

As a scholar, he focused on preserving people’s stories, artifacts, Spanish heraldry, and traditions through archives and educational programs.

Vásquez y Sánchez died in May 2023 at age 83. Family and friends celebrated him for his wit, humor, and strong legacy as an artist, historian, civil leader, and “cultural superhero.”

Learn more:

- His artwork at The University of Texas at San Antonio

- A Texas Senate resolution honoring his legacy

- Listen to a 2018 oral history conducted by San Antonio College's Mexican American Studies program

Bessie Coleman

Bessie Coleman was the first woman of Black and Native American descent to earn a pilot’s license in the United States.

Elizabeth Coleman was born in 1892 in Atlanta, Texas. Her Native American legacy came from her father, who was part Choctaw and Cherokee.

As a young adult, she moved to Chicago for a better life, determined to escape the gender and racial discrimination in Texas.

When Coleman's brother John returned from service in World War I, he told her stories about women pilots. Coleman was inspired.

Flying schools in the U.S. rejected her because she was Black and a woman, so she moved to France.

Her brother’s stories proved true. Coleman earned her international pilot’s license in 1921.

But she wasn’t content to be an ordinary pilot. Coleman trained to be a stunt pilot. She dazzled European and U.S. audiences with her daredevil performances.

She also combated discrimination by refusing to speak or perform in segregated spaces.

But her brilliant career was cut short. On April 30, 1926, Coleman died in a test flight crash before an airshow.

In 2023, the U.S. Mint included Coleman in its special series of new quarters. The 25-cent coin design depicted Coleman preparing herself for her next flight.

Learn more:

- The National Air and Space Museum

- National Women’s History Museum

- "American Experience" on PBS

- The Smithsonian Institution

- The University of Houston's Cullen College of Engineering

Juan Rodríguez, or El Cuilón

Juan Rodríguez, or El Cuilón, was an Ervipiame chief who helped found the Spanish missions in San Antonio, Texas, in the eighteenth century.

He was born around 1660. He led the Ranchería Grande tribes, a loose confederation of Tonkawa and Coahuiltecan people who lived in Central Texas.

In 1718, Rodríguez met Spanish Gov. Martín de Alarcón at the San Antonio de Valero Mission, later known as the Alamo, to establish friendly relations.

Alarcon named Rodríguez “Lieutenant Captain-General of the Province of Texas.”

For the next four years, Rodriguez worked as a scout, interpreter, and intermediary. His family and other Ervipiame families moved to San Antonio.

Rodríguez asked Spanish officials to build two new missions, San José y San Miguel de Aguayo and San Francisco de Nájera.

Rodríguez hoped the new missions would help create a more peaceful society.

By the time Rodríguez died in 1735, his efforts had transformed the Spanish missions into thriving and tangible communities.

Learn more:

- The Handbook of Texas

- "Diary of the Alarcón Expedition into Texas, 1718–1719," by Fray Francisco Céliz and F. L. Hoffman

- "The Alamo Chain of Missions: A History of San Antonio's Five Old Missions," by Marion A. Habig

Sophia Alice Callahan

Sophia Alice Callahan was the first Native American woman to write a novel and see it published.

She was born in Sulphur Springs, Texas, on New Year’s Day 1868. She was of Muscogee descent. Her family fled Oklahoma during the Civil War and moved to Texas.

Callahan became a teacher, and in her twenties, she wrote Wynema, a Child of the Forest, the story of a Native American girl who becomes the student and friend of a white missionary woman.

The book was published in 1891. Callahan earned no money from the novel, and she died from illness three years later. She was 26.

She was relatively unknown until a historian found her book in the Library of Congress in 1955.

Since then, Callahan’s novel has been influential in the study of women’s rights and of injustices to Native Americans.

Learn more:

- The Handbook of Texas

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma

- Read the novel (courtesy of the University of Illinois at Chicago)

Millie Thompson Williams

Millie Thompson Williams was the first woman elected second chief of the Alabama-Coushatta tribe.

She was a member of the Bear Clan. Williams was born in 1956 on a reservation in Polk County, Texas.

She earned a degree in child and family development from Angelina College and then served as a teacher in the Head Start Program for more than 35 years.

Williams also led Sunday school classes at the Indian Village Assembly of God in Livingston.

She also worked to instill cultural values in the younger generation by teaching them traditional handicrafts and the story of the tribe's fight for sovereignty.

Williams used her status to encourage young women to pursue their dreams. She was elected as second chief in January 2023. She was a tribe ambassador and advised the tribal council.

She died in August 2023 at the age of 67.

Learn more:

Chief Bowl

Chief Bowl was a Cherokee political and tribal leader who died leading a resistance effort against Texas.

He was born in 1756. He led a group of Cherokees originally located in Hiawassee, North Carolina.

In Texas, Bowl became the “civil” chief or “peace” chief, a key position in a council that united several Cherokee villages. He worked tirelessly to secure land rights for his people and sought to settle areas from East Texas to Mexico.

Despite his efforts, he could not escape the low regard white Texans held for Native American confederations.

After several failed negotiations with the Texas government, Chief Bowl led his warriors in a resistance movement. He died in the Battle of Neches in 1839, the last battle of Cherokee resistance against white Texans.

Learn more:

The Sacred Springs

Native Americans in Texas treasured the region's many life-giving springs, especially the springs in San Marcos, a region which the Coahuiltecan tribe considers its birthplace.

The area around Spring Lake, born from the San Marcos Springs, has been continuously inhabited and has served as a holy site of pilgrimage for thousands of years.

The tribe’s modern descendants celebrate their traditions with a festival at Spring Lake every October. They fill the space with music, dance, and food. Members of the public are always welcome to join them.

The San Marcos Springs are just one of several important springs in the state that people can visit.

West Texas has the Comanche and San Solomon Springs.

Krause Springs, Jacob's Well and Barton Springs are in Austin and the Hill Country.

The Blue Hole is between San Antonio and Alamo Heights, and Comal and San Marcos Springs are nearby.

They brought life, health, spirituality and serenity to Native Americans for centuries, and they continue to do so today.

Original inhabitants of San Antonio Missions

The Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation descended from Native Americans who converted to Roman Catholicism in the early 18th century.

They are not recognized by state or federal governments.

In May 2001, state legislators celebrated them as "the first cowboys" and for their contributions to engineering and agricultural projects.

Later that year, the City of San Antonio celebrated the nation's "distinguished history" and "pivotal role in Texas' development."

In 2019, The Texas House passed a bill that would have recognized the nation. The status would have streamlined how they and their nonprofit organization, American Indians in Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions, worked with government agencies. But that bill died in the Senate (a similar bill emerged in 2023 but made little progress).

The 2019 legislation was written at the same time that plans for the $500 million Alamo renovation were finalized.

The Tap Pilam consider the Alamo area — originally known as Mission San Antonio de Valero — to be sacred burial grounds, which has challenged the narrative of Alamo history.

Learn more:

- The Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation's official website

- Archival resources and special collections at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley

- "Reclaiming Tribal Identity in the Land of the Spirit Waters: The Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan Nation" by Adrian Chavana

The Caddo Mounds

The Caddo Mounds form a state historic site in Cherokee County, north of present day Houston.

The Caddo people were the earliest settlers in the region, and they built this ceremonial center more than 1,200 years ago.

The complex projected its influence across trade networks stretching as far away as the Great Lakes region, which provided copper, and Florida, which provided valuable sea shells.

The Caddo culture was agricultural, and corn was its dominant food. The people were skilled potters and basket makers.

Despite its success, the Hasinai Caddo gradually moved away from the site, and the people spread out into nearby regions before the U.S. government forcibly resettled them in Oklahoma.

Texas gets its name from "tejas," the Spanish spelling of the Caddo word "taysha," which means "friend" or "ally."

The Mounds are also on El Camino Real de los Tejas, one of the Spanish Empire's royal roads built to connect the region to Mexico City.

Council House

In March 1840, Comanche tribal chiefs came to San Antonio's Council House with the aspiration to build a brighter future with their white neighbors. They wanted to live peacefully on their land.

But the Texans wanted the Comanches to leave the land to them, stop raiding white communities and return hostages they had taken.

As the Comanche chiefs gathered, the Texans decided to take them hostage to force other Comanches to return the white prisoners.

The chiefs decided to fight their way out of their dilemma, and the ensuing battle was a bloodbath. All 12 chiefs were killed along with 23 other Comanches. Seven Texans also died.

The Comanche tribes retaliated with an attack remembered as the Great Raid of 1840.

What might've been a turning point for peaceful relations instead became the prologue to more bloodshed and distrust.

The Acto de Posesión

During the eighteenth century, Spanish friars established five socio-economic missions among the indigenous San Antonio population. In one generation, Coahuiltecans and other tribes became farmers and ranchers.

The Acto de Posesión occurred on March 5, 1731, when Franciscan friars turned over management of the missions to the Native American families there.

The indigenous people who lived and worked the land now owned three of the frontier missions: Concepción, Espada, and San Juan Capistrano.

Four days later, Spanish officials arrived to establish colonial rule. While that rule fostered a common religion and language that eroded indigenous cultures, Native Americans at the missions developed a new, blended culture.

Today, their descendants are rewriting the narrative to highlight the culture and contributions of the indigenous people who created these communities.

Learn more:

- "The San Antonio Missions and Their System of Land Tenure," by Félix D. Almaráz

- The National Park Service

- UNESCO

- Coverage of the Missions at TPR

Lipan Apache feathers

The Lipan Apache of Texas did not sign an 1868 peace treaty with the federal government, so it is not a federally recognized tribe.

That official recognition was required for any tribe to include eagle feathers in their religious celebrations without fear of prosecution.

Multiple federal laws protect the animal. Indigenous people believe the eagle is sacred.

In 2006, undercover federal agents raided a Lipan Apache religious ceremony in McAllen, Texas.

They confiscated 42 eagle feathers from Pastor Robert Soto, vice chairman of the tribe. He wore them in a ceremonial headdress. They also took feathers from another participant who wore them on a garment.

After a 10 year court battle, the case was settled in 2016. Soto and his worshippers were allowed to use the feathers again.

Soto later asked the government to adjust its policies so Native Americans from non-recognized tribes like the Lipan may use the feathers without fear of prosecution. As of 2023, that issue remains unresolved.

Diane Joyce Humetewa

Diane Joyce Humetewa was the first Native American woman to become a federal judge.

She was born in Phoenix in 1964 and grew up partly on the Hopi Reservation in northern Arizona.

Humetewa studied criminal justice at Arizona State University. She worked as a crime victim advocate, particularly for tribal members. Her mentors encouraged her to attend law school. She later worked in the Senate and in the Clinton administration's Justice Department.

In 2007, Humetewa became the first Native American woman to be named U.S. attorney.

She later served as a judge and prosecutor in the Hopi court system and tried to find ways for the federal and tribal court systems to better work together.

In 2013, President Barack Obama nominated her to serve as a U.S. district court judge in Arizona. She was confirmed the following May.

Learn more:

- Humetewa's 2021 profile in "The Federal Lawyer," by Trevor W. Carolan

Jim Thorpe

Jim Thorpe was one of the greatest all-around athletes in U.S. history.

Thorpe was born on the Sac and Fox reservation in Oklahoma in the late 1880s.

He attended Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania and excelled in track and football.

Thorpe’s greatest success came during the 1912 Olympics. He won gold medals in the pentathlon and decathlon.

His triumph ended abruptly when a reporter revealed that Thorpe briefly left high school to play semi-professional baseball, a violation of Olympic rules.

Thorpe lost the medals.

Nonetheless, he built a successful career in professional baseball and football.

He died in 1953. Ten years later, he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

His children pressured the Olympic Committee for years to return Thorpe's gold medal wins.

The committee did so in 1982. But it did not change the record books to list him as the winner of those contests until 2022.

The U.S. Postal Service celebrated Thorpe twice — in 1984 and 1998 — with commemorative stamps.

In 2018, the U.S. Mint included Thorpe in its special series of gold dollars honoring Native Americans and nations. The coin design depicted Thorpe as a football player and Olympic athlete. It was inscribed with the names "Jim Thorpe" and "Wa-Tho-Huk," his indigenous name.

Learn more:

Joy Harjo

Joy Harjo was the first Native American Poet Laureate of the United States.

She was born into the Muscogee -- or Creek -- Nation in Oklahoma in 1951.

She grew up watching her community endure alcoholism and poverty. She attended school in New Mexico and worked as an environmental activist. She fell in love with music and painting.

Harjo discovered her voice when she discovered poetry. Her poems draw from Native American stories, language, and traditions. She's published numerous books of poetry, memoirs, and children’s stories.

She was named U.S. poet laureate in 2019.

Harjo has explained in interviews that her poems carry her dreams, her knowledge and her wisdom. Together they weave a tapestry of spirituality that connects her to the world around her.

She said she wants her poetry to connect people, to overcome their political divisions and to provide a safe space for them to exchange their feelings.

Learn more:

Clarence L. Tinker

Clarence L. Tinker was the first Native American to become a two-star Army general.

Tinker, a descendant of the Osage people, was born in Oklahoma in 1887, and graduated from a military school in Missouri in 1908. He became an Army infantry officer in 1912.

In 1920, he decided to learn to fly as he climbed the Army ranks.

By the time World War II began in 1939, Tinker commanded the 27th Bombardment Group.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, Tinker was promoted to major general — the highest ranking Native American in the U.S. Army — and appointed commander of the 7th Air Force.

On June 7, 1942, he led four LB-30 bombers on a raid on a Japanese fleet near Wake Island in the Pacific. But his plane malfunctioned and crashed into the ocean. Tinker and his ten crewmembers were killed.

Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma is named in his honor.

Every year, the Osage people honor Tinker with a song celebrating his legacy.

Learn more:

- The 7th Air Force

- "Native Americans in the U.S. Army" and "Native Americans in the Pacific War"

- "The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture"

- “Hidden Treasures from the Stacks: From Haskell to Midway: Major General Clarence L. Tinker,” by the National Archives in Kansas City

- Sequoyah National Research Center at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock

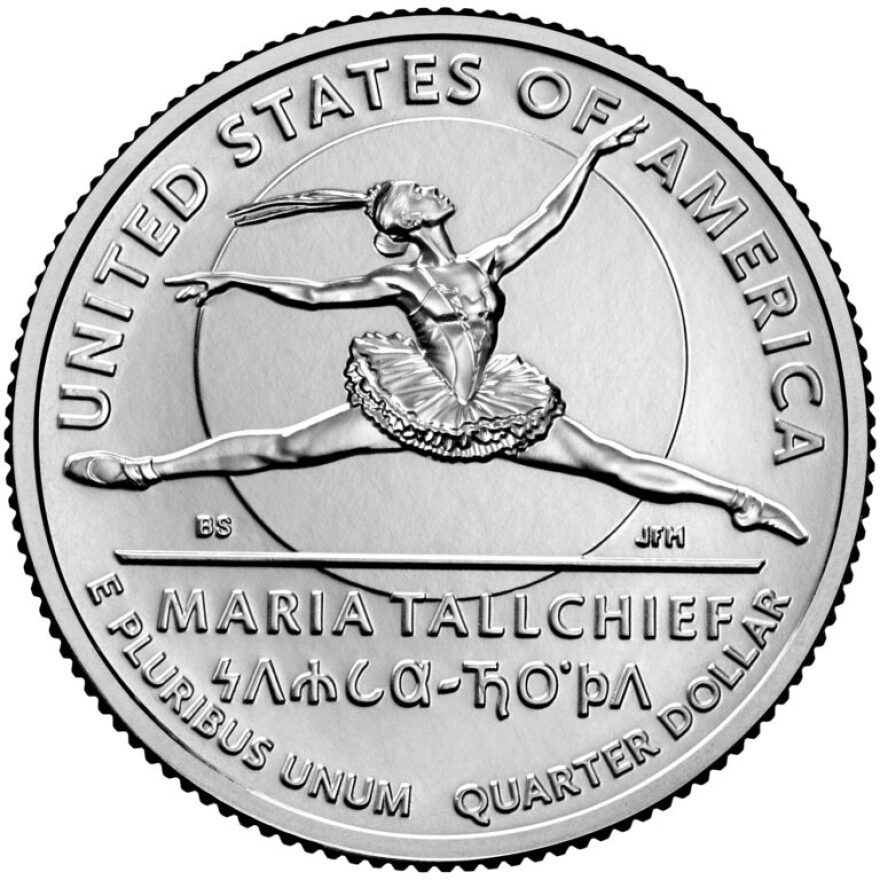

Maria Tallchief

Maria Tallchief, an Osage woman, became a ballerina who was celebrated around the world.

She was born on the Osage Indian reservation in Oklahoma in 1925.

When she was 17, she moved to New York to study ballet. Friends concerned about discrimination advised her to change her name but she refused.

She danced with the leading Russian ballet company. She later became the first American to dance with the Paris Opera Ballet and to perform at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow.

In 1949, Tallchief starred in "The Firebird" to rave reviews, leading the New York Ballet to name her its prima ballerina.

She later moved to Chicago and used her fame to help other dancers and to call out discrimination against indigenous people.

In 1999, she was awarded the National Medal of the Arts.

In 2023, the U.S. Mint included Tallchief in its special series of new quarters. The 25-cent coin design depicted Tallchief in midair, arms and legs outstretched, with her English and Osage names inscribed underneath.

Learn more:

- Wahzhazhe: An Osage Ballet

- The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

- National Women's History Museum

- School of American Ballet

- Library of Congress

Charles George

Private First Class Charles George was a recipient of the Medal of Honor.

The Cherokee was born in North Carolina in 1932, in a town named Cherokee.

He was 18 when he entered the U.S. Army, and two years later he was fighting in the Korean War.

On Nov. 30, 1952, George was a member of a raiding party searching for potential prisoners. They soon made contact with enemy soldiers, and a fierce battle began.

When a grenade landed near his comrades, he threw himself on it to shield his fellow soldiers from the full force of the explosion.

George later died of his injuries. He posthumously received the Medal of Honor in 1954.

Memorials, bridges, gyms and a U.S. Army installation in South Korea were among the ways his bravery was remembered.

Ola Mildred Rexroat

Ola Mildred Rexroat was the only Native American woman known to have served in the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP).

Rexroat was born in Kansas in 1917. Her mother was an Oglala Lakota originally from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, where Rexroat spent much of her childhood visiting her grandmother.

When World War II broke out, she joined the WASPs and received flight training in Sweetwater, Texas.

Rexroat flew fighter aircraft and performed the dangerous job of piloting planes that towed targets for gunnery practice.

After World War II, Rexroat served in the Air Force for ten years before joining the Federal Aviation Administration, where she worked for 33 years.

In 2007, she was inducted into the South Dakota Aviation Hall of Fame.

In 2009, Rexroat and other WASPs received a Congressional Gold Medal.

She died in 2017 at the age of 99. She had been the last surviving WASP in South Dakota.

Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota named its airfield operations building after her to honor her wartime service.

Quanah Parker

Quanah Parker was born in Oklahoma around 1848 to a Comanche warrior and Cynthia Ann Parker, a white woman.

He grew into an experienced warrior and became the leader of the Quahada band of Comanches, bison-hunters of the Llano Estacado.

The Quahadis were among the last Native American groups to successfully resist the federal persecutions. They held the Texas Plains for seven years before U.S. forces hunted them down southeast of Lubbock, Texas.

In 1875, Quanah led his followers to the Comanche Kiowa reservation and resolved to lead his people into a new future. He transformed himself into a diplomat, politician, and businessman.

Quanah succeeded as a cattleman. He embraced technology, becoming one of the first in the nation to install a phone and buy a car.

He built a ten-room, two-story home in Oklahoma and named it the Star House, where he entertained a constant flow of visitors, including President Theodore Roosevelt.

But Quanah never turned away from his cultural roots, and he embraced his religious beliefs all his life.

As principal chief of the Comanches, Quanah used much of his income to help his people with food, education, and housing.

He died in 1911.

Learn more:

- Resources at the Library of Congress

- "The Naming of Quanah," a painting by Jerry Bywaters, National Postal Museum

Standing Bear v. George Crook

Standing Bear was chief of the Ponca tribe.

In 1858, the tribe signed a treaty with the U.S. ceding a large portion of its land in Nebraska.

Ten years later, the federal government gave that small tract of land to the Sioux tribe … and then forcibly moved the Ponca to Oklahoma.

Many of them -- including Standing Bear's teenage son -- died during the first winter.

The chief wanted to bury his son in Nebraska and tried to return. But he had left the reservation without permission.

The U.S. government ordered Army Brig. Gen. George Crook to arrest Standing Bear.

But spurred by the injustice of the arrest, Crook helped Standing Bear petition the courts for his right to return to his homeland.

In the case "Standing Bear v. Crook," the U.S. government argued that Standing Bear was neither a person nor a citizen and could not sue the government. The judge disagreed and ruled in favor of the chief.

Standing Bear peacefully lived with his people in the Ponca homeland. He died in 1908.

In 2019, he was honored with a statue in the U.S. Capitol’s National Statuary Hall. In 2023, the U.S. Postal Service placed him on a Forever stamp with a design based on an 1877 photograph.

USPS issued the Chief Standing Bear Forever stamp today. The civil rights icon, won a landmark court ruling in 1879 that determined a Native American was a person under the law with an inherent right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.#ChiefStandingBearStamp. pic.twitter.com/wGDzxwjteg

— Tim Norman (@USPS_TimNorman) May 12, 2023

The Snyder Act

The Snyder Act of 1924 is also known as the Indian Citizenship Act.

The Act granted full citizenship to Native Americans born in the United States.

It came about, in part, to reward Native Americans who fought in World War I.

The impact of the Act was limited, however, because it let states decide whether or not Native Americans could vote.

States with large Native American populations typically kept tribal members disenfranchised, both through legislation and by deploying Jim Crow era intimidation tactics.

Native American heroism during World War II would help shift the tide. In 1948, Arizona finally struck down its law preventing Native Americans from voting. Other states followed suit.

By the time the Civil Rights Act in 1965 became law, Native Americans had been granted the right to vote in all states.

More resources

- Reading ideas from the San Antonio Public Library:

Fiction | Nonfiction | For children - Reading ideas from the Library of Congress:

Fiction, nonfiction and video interviews