Sign up for TPR Today, Texas Public Radio's newsletter that brings our top stories to your inbox each morning.

It’s truly a riddle wrapped in an enigma. A small-town Texas librarian finds a musty old Bible and soon realizes it's unlike any she’s ever seen. It’s hundreds of years old and written in a familiar, but dead, language.

Texas Public Radio looked into it and uncovered ... well, most of its mystery.

First off, the town is Boerne, about 20 miles northwest of San Antonio, founded by German immigrants in 1849. Secondly, the mystery language: Although this Bible predates the country of Germany, it was written in German … a variation of German.

Elisa McCune knows this Bible well. She wrote her doctoral dissertation on it.

“High German was spoken in the southern half [of what’s now Germany], and Low German was spoken in the northern half,” she said. “High German, essentially, was what turned into what modern day German is. Low German was considered to be—and I'm probably, simplifying this a little bit—but it was the less sophisticated version of German.”

This Bible was written in Low German. Easier to determine was this Bible’s age. Here, McCune reflects on when she first became aware of the Bible while working at the Boerne Public Library.

“It was a 1614 Low German Bible. It was rare, and we had only one of seven copies in the world,” McCune said.

Of those seven, one is in Boerne.

There’s also one at the Royal Danish Library.

McCune added that "the British Library has one. There are a couple in Germany, and then there's one in Chicago, at the Newberry library,” she said.

“Boerne is the only public library that has [one], it's pretty interesting that a town as small as Boerne has this for sure.”

Solving the mystery of when and where it was published was simple because its publishing info is printed in the Bible itself. Also, records show that plates from this Bible were used to publish a predecessor, something called the Wolderbible. Its publisher went out of business. His misfortune created opportunity for a man named Hans Stern.

“And so Hans Stern was able to purchase the plates, and he was able to get everything done more cheaply than the Wolderbible’s creator was able to, so he was able to turn a better profit,” McCune said. “And in fact, the Hans Stern publishing house is still in operation today, or was at the time that I wrote my dissertation in 2012!”

She’s right. The publishing business Stern started in the 1600s still prints Bibles in Lüneburg 411 years later, and the plates used to publish Boerne’s Bible are on display at Lüneburg’s public library. The significance of the 1614 Bible goes beyond its incredible age, though. Unlike most of its predecessors, it wasn’t printed in Latin.

“Martin Luther was excommunicated for his idea that people should be able to read the Bible and the language that they speak, and so this book would have been produced ... it was after Martin Luther did his whole theses and then nailing to the door and all that stuff,” she said. “This is a relatively new phenomenon that people did find after they started printing books, or printing Bibles in German rather than Latin.”

McCune is referring to Martin Luther nailing 95 theses (some historians suggest they were pasted) to various doors on October 31, 1517. The theses were a set of arguments against certain practices of the Catholic Church. He refused to recant his writings and was subsequently excommunicated by Pope Leo X in January 1521.

Since few other than priests from the Catholic Church spoke Latin, the church was the only avenue for religious study. And in a sense, printing this Bible in Low German was the first step that would eventually lead to reading for reasons other than religious ones.

“The whole idea of having books that people read for pleasure, eventually you get there, but it all kind of starts with people making Bibles in the vernacular versus in in Latin,” McCune said.

Catherine Schwarz first found the Bible at the old Boerne High School, located where Boerne Middle School North is located.

“I had just been hired as the librarian for the high school of Boerne. I gave it to the historical society, and they kept it a good while,” Schwarz said.

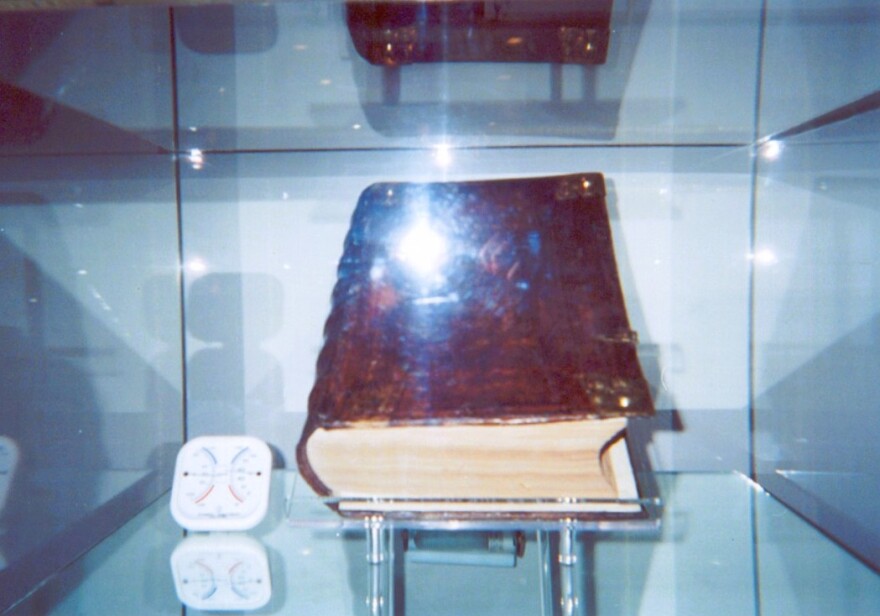

The Boerne Area Historical Preservation Society displayed it and kept it from harm. Eventually, they gave it to the city of Boerne. Given that it was over 400 years old, it was in rough shape.

It was sent to Mary Frederickson in Canyon, Texas to be restored.

Robin Stauber is with the Boerne Public Library.

“[Frederickson] was the one that painstakingly put it back together and helped with the spine cover,” Stauber said. After she finished with the restoration process, and the Bible came back to the library, a case was created for it, and so it was on display from then on, until recently, until two years ago, when we sent it off to the University of North Texas to get digitized.”

The University there painstakingly digitized every page. Stauber said the Bible is back, but because of a sunlit lobby, it isn't displayed there as it had been. Not to worry Stauber said; you can still see it.

“Still publicly accessible. If anybody wants to come see it, just give us a call. We have archive hours here Tuesday through Friday, so they could always just come in and take a look,” she said.

Students at the University of North Texas are going to make it accessible by early fall in ways it’s never been before.

“They are meta-tagging it so they are developing code words and searchable items to go be able to go through the Bible and look at it, and then once they put all that together, it will be online at The Portal to Texas History. So anybody can get in there and take a look at it,” Stauber said.

UPDATE: The University of North Texas has completed their work and the Bible is now available online here.

Another factor to consider: this isn’t a Bible for personal contemplation. It’s a hefty book! Elisa McCune.

“It would not be comfortable to sit with in your lap for a long time. It would probably have been displayed on like a lectern at a church, for example,” she said.

The 1614 Low German Bible of Boerne, Texas: an Examination of its Origins and Lasting Influence in the Live... by Texas Public Radio on Scribd

It’s nearly 12 and a half pounds, 16 inches long, 10-plus inches wide, and 4 inches thick. If you think back on the journey this massive tome took, it was probably on a sailing ship for between six and eight weeks, then a week on horseback to Boerne from Galveston. Whoever brought this Bible to Texas and then brought it to Boerne was probably quite religious.

“Who loved it? Who thought it was essential to take all the way over to Texas from Germany, who valued it and thought that it was important? And clearly, it was passed down through the people in the family that owned it,” McCune said.

And that brings us to the name scrawled inside the cover.

“This book does have, actually more than one name, fortunately, on the inside of the covers. On both the front and back cover, it has the name Johan Schwarting. It also has a date of 1660 so that's really great,” she said.

1660 is almost 200 years before any Germans lived in Boerne—so did the Schwartings move here?

“I have done some digging, and I have not found any evidence of a member of the Schwarting family in Boerne proper,” McCune said. “It's very likely that it was brought over from Germany by a member of this family, but it could have been a daughter, or somebody who ended up with a different last name.”

We may never know who brought the Boerne Bible there, but perhaps the digitized contents accessible worldwide will open a portal that didn’t exist in the misty past.