It took three weeks for Raymond Lopez to start eating again. The first few days were some of the worst he said, but from his descriptions — not eating the food at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s Coffield Unit wasn’t that much of a sacrifice.

“It’s like I don't know what it is,” said Lopez of the food. “I mean, the other day they bought us some spaghetti, and they had some tuna fish on the side of it that I don't even know what even gave it to my dog."

Ultimately, dizziness, starvation and blood pressure forced the 67-year-old to eat.

It’s been just over a month since the hunger strike roiled Texas prisons, and some inmates have said they are willing to do it again. Dozens of men went weeks without eating to protest the use of indefinite solitary confinement by the state, which in Texas is called Security Detention. Reform advocates have said as many as 130 men refused food concurrently, while the state confirmed only 72.

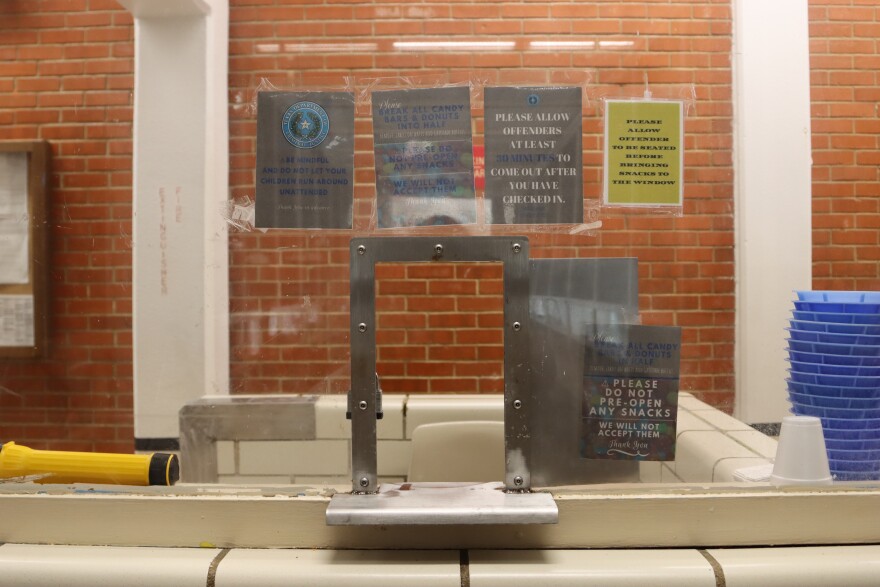

In Texas, thousands of people spend more than 22 hours a day in cells. The men describe cramped rooms which include a bed, a sink and toilet.

The United Nations has called for an end to extended solitary confinement, calling it inhumane. The state has said it has no plan to change the practice because they said it keeps prisoners and guards safe.

Lopez — a habitual offender — is serving 75 years for stealing a car. He has been in and out of TDCJ since 1978, first serving a 2-year stint for heroin possession. The drug was the reason his parole was revoked in 2011.

He’s spent 27 years total in solitary confinement for being a Mexican Mafia member. The prison gang is one of 12 classified as security threat groups by TDCJ. Membership in the criminal organization carries with it mandatory solitary — barring an inmate from substance abuse, education and job programs.

Texas is one of a handful of states that still uses this “status-based” segregation or putting people in solitary for their membership in a specific prison gang. About 1,250 of the more than 3,100 people in solitary are there for being members of a security threat group or prison gang. Of those, most have no major disciplinary issues in jail — less than 10%.

Lope said this isn’t fair, and he went on strike to help end the practice and also to improve how they are treated. But that hasn’t changed.

“Well, still nothing. Still nothing,” he said about what has changed. “They just don't have no officers. You know, there can be no impact with ain't got no officers — we still get messed over.”

Coffield is one of the least staffed Texas prisons, with a 60% vacancy rate, according to state data. Inmates in solitary have complained the staffing has led to issues accessing recreation time and showers. Jails, prisons, and state hospitals have all struggled to find labor since before the pandemic.

The primary goal of the coordinated hunger strike, Lopez said, was garnering attention outside their prison walls, which they did accomplish. Both statewide and national outlets carried news from inside the state’s prisons.

Lopez said the conditions inside the 50 year-old Coffield prison were abysmal. Aside from the aging infrastructure that turns showers into either ice baths or scalding with water better for coffee. He said the lack of air conditioning turns the front of his cell into a stainless steel frying pan, sometimes literally.

“When it's summertime, you can put a sandwich on there, and it's gonna get hot, he said. “In wintertime. It's so cold, It’s,” but instead of saying a word he grimaces in pain.

“Your mind can only withstand so much,” he said of the conditions.

The man has seen several others break under the weight of solitary confinement, the psychological impacts of which have been compared to physical torture.

Sitting in the interview booth next to Lopez is Joshua Sweeting, a member of Aryan Circle, another STG. Two small lightning bolts adorn Sweeting’s face, sitting near his left eye — the SS Nazi imagery just one of many signifying his membership in the white supremacist gang.

Sweeting said they put themselves in prison but they are still people. He questioned the wisdom of barring the men — many of whom will get out at some point from job programs, substance abuse programs and others that could help them stay out of prison.

Sweeting agreed with Lopez that the main goal of attention had been achieved but also said the fact that the two men can sit side by side and ask for change is in and of itself a success for their cause.

“It's not like it used to be back in the day. Back in the days, you would have never caught me and this man here socializing with each other,” Sweeting said.

Back in the day, gangs in Texas prisons erupted in violence. In the mid 1980s when the country saw a surge in prison populations. Texas saw more than 50 murders (90% gang related) in just a two-year period, more than the previous 20 years combined.

Stowing racial and other gang grudges was key to similar reform efforts in California that resulted in change to how that state administers solitary confinement.

“There's not many blueprints for this, across the country,” said David Pyrooz, sociology professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, researching prisons.

“But California is probably the closest prisoner-lead reform movement that we've seen.”

He said — like Texas — there were multiple hunger strikes in California over several years with some efforts going unnoticed before it spread, growing in 2013 to the tens of thousands.

“They move with these fits and starts, where there's an effort, and then it gets to a point of exhaustion. And eventually, there's this groundswell of additional interest that will lead to a greater commitment to it and more participation,” he said.

The state said they use solitary confinement to keep prisoners and guards safe — and the threat posed by STGs is too great to allow them to continue to recruit.

The two inmates TPR spoke with disagreed with TDCJs assessment that releasing them would lead to more violence.

Both incarcerated men say they are open to striking again. During the strike the state slowed down their email, Sweeting said, a charge the TDCJ denied, blaming week long delays on volume. TDCJ did bar journalists from in-person interviews explicitly to tamp down on the hunger strike. Sweeting said he will without a doubt participate in another strike if it means they can change the way inmates like them are treated in Texas.

“It sucks you have to put your body through that, And you got to starve yourself in order to be taken seriously,” he explained. “But realistically it's the only way for the outside to hear our voice.”

They can’t cover up a hunger strike, he added. Their choice of to eat or not is one of the few the men have left.