San Antonio's largest citywide celebration, Fiesta, has come and gone. However, there’s one more Fiesta story to tell — and it’s one you don’t hear that often: Quite a few San Antonians don't actually like Fiesta, or at very least, they’re conflicted about it.

Originally published on April 30, 2018.

"You can't talk about Fiesta without talking about race," said Lilliana Saldaña, who grew up on the city's south side and is an associate professor of bicultural-bilingual studies at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

"Fiesta is the commemoration of Anglo victory at the Battle of San Jacinto. It commemorates the ‘fallen heroes’ at the Alamo and San Jacinto. So in a way, it does celebrate white supremacy," she said.

Also, when the Alamo fell, the men fighting inside the mission weren't fighting for Texas. There was no Texas. This was Mexico.

Another thing that doesn’t sit well with Saldaña is the high end of Fiesta — the Texas Cavaliers and the “royalty.”

"Anglo elite place themselves as sort of cultural guardians of the city of San Antonio, which is why they have this fake monarchy, and they have pseudo military," she said.

She takes norms and traditions of Fiesta pretty seriously, and she dismisses the idea that Fiesta is just a party.

"Well, you can't really understand Fiesta without understanding the historical origins of Fiesta, which are very problematic," Saldaña said.

Denise Hernández’s views are far more conflicted.

"I love Fiesta, personally,” she said.

Hernández is an activist, educator, and sixth-generation San Antonian.

"I've been performing ballet folklorico since I was four years old,” she said. "I appeared on some floats in the Battle of Flowers and then the Fiesta Flambeau parade. We performed at the Arneson."

While Hernández said she loves Fiesta, she also kind of hates it.

"There's royalty, and these gowns that cost more than our rent, more than our mortgages. We can celebrate such wealth and such extravagance while, you know, folks who are still living in shacks and don't even have a high school education? I can't reconcile that," she said.

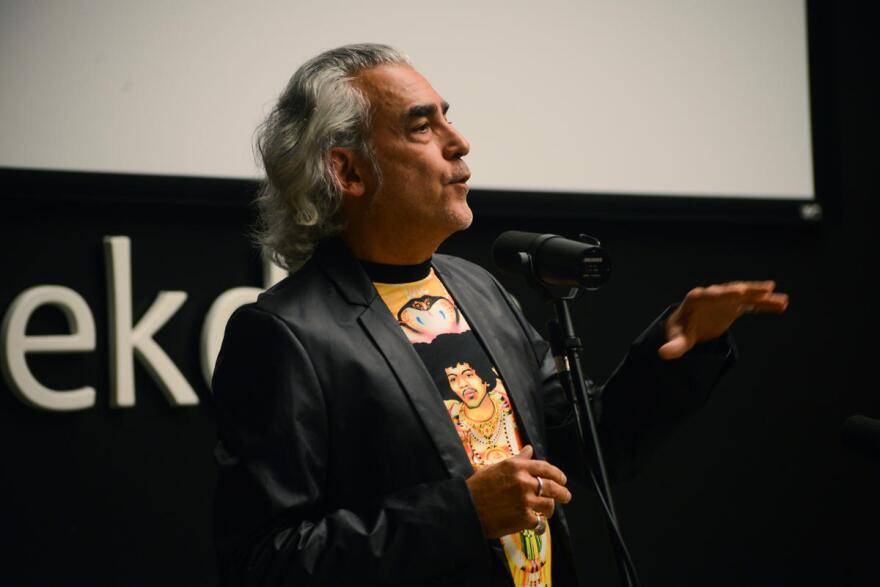

John Phillip Santos followed his Fiesta memories back more than 50 years.

"So grandmother ... introduced us to the idea of Fiesta, but she always said that it was the craziest thing because it was Mexicans celebrating the defeat of the Mexicans," he said.

The other memory that stuck out for Santos, who is a writer, producer and Rhodes scholar, was when King Antonio would come every year to visit his school.

"He was always like in this open convertible, so there was a kind of ostentatiousness,” Santos said. “It was a very aggressive way of interfacing with us ... kind of distant and royal. It wasn't anything where we saw ourselves -- the Mexican American community didn't see itself reflected in the Fiesta as a ritual."

But then Santos left San Antonio to study abroad and then lived in New York City for 22 years. When he moved back to San Antonio in 2005, Fiesta felt completely different.

“It has all been sort of transformed from within. There was a kind of undercurrent of insurgent change that was beginning to reshape the iconography of Fiesta, the identity of Fiesta, turning it into a more carnivalesque affair, lampooning royalty, and becoming outright ironic in certain, in certain, specifically the Cornyation events,” he said.

Cornyation lampoons most of Fiesta’s stodgier aspects. And Santos said the narrative of Fiesta had morphed into something those who created Fiesta probably wouldn't recognize.

"Increasingly aware of how much stories of migration and immigration had played out in shaping San Antonio. That we were always a place of confluence, that we always were a place — a kind of a crossroads,” Santos said. “There was certainly nothing along those lines that was ever observed or celebrated during Fiesta, which you see now."

Santos said Fiesta, while quite important, is only part of a much larger picture.

"Our city, 300 years old, was founded under the sun of another empire. You know, we were founded in the time of New Spain,” he said. “That story, in a sense, was linked as well to the deeper indigenous origins of this place that, we're told by archeologists, go back 10,000 years. We are a cosmic city, the ciudad cosmica, and that turns out to be an epic story."

Jack Morgan can be reached at Jack@TPR.org and on Twitter at @JackMorganii.