This story is part of the TPR series Between Here and Home, which explores how Afghans are navigating life in San Antonio after the war.

Like many recent Afghan immigrants, the Shinwari family was evacuated by the U.S. before Afghanistan fell to the Taliban in the summer of 2021.

Mursalin Shinwari was an interpreter for the U.S. Army in Afghanistan before the withdrawal.

“I worked as a translator for the U.S. Army for almost three years,” said Mursalin, sitting cross-legged on the rug in his San Antonio apartment with his toddler on his lap.

Mursalin now works at San Antonio’s halal grocery store. He and his wife Basmina have five children under the age of 10. She filmed the conversation with TPR on her phone while their baby leaned against a big cushion next to them and drank from a bottle. Their older children watched cartoons nearby.

The main room of their apartment in the medical center was covered in a wall-to-wall plush red rug. They took their shoes off at the front door and sat on the rugs to talk and eat. They offered a loveseat couch for guests. A clock on the wall listed Islam’s five daily prayer times.

Mursalin said their oldest two children, Yasar and Sana, were enrolled in school back in Afghanistan, but they didn’t go very often.

“Many times, parents are afraid that they send their children to the school in Afghanistan so the Taliban will kill them — the Taliban will ... blast their schools,” Mursalin said.

Rather than risk their children being attacked on the way to school, he said he and his wife often decided they were safer at home.

Then, when they arrived in the U.S., the Shinwaris lived on a military base for months without access to school.

“There were not facilities of education in the military base. So, they lost their education and experience with education,” Mursalin explained.

By the time they arrived in San Antonio about a year and a half ago, Yasar and Sana had some catching up to do.

But Mursalin said schools here are like night and day compared to Afghanistan. They have resources — and school buses — and English lessons. And they’re not worried their children will be targeted for getting an education.

Yasar just finished second grade at Mead Elementary; Sana was in first grade. Sana said her favorite thing to do at school is draw but she’s also learning other skills.

“I speak English. And I [learn to] be kind to my friend,” Sana added.

She explained that she recently went on a field trip to the zoo. “There was [a] giraffe and [a] lion and ducks. There was lots of ducks.”

The Shinwaris live in an apartment complex near San Antonio’s medical center, like many refugees and immigrants who received help from resettlement agencies when they arrived. That proximity gives them a community that follows them to school.

Yasar and Sana’s school, Mead Elementary, is just up the hill from several medical center office buildings. It’s one of five elementary schools in the Northside Independent School District with Newcomer classes, which are specially designed for children whose education was disrupted by war or persecution before they arrived in the United States. Mead has one Newcomer class per grade.

“The program is designed to give the kiddos a smaller ratio per teacher. Plus, we have an instructional assistant that rotates through all of the six classes,” said Mead Principal Amanda Garner-Maskill. “It's a little bit of a slower transition. Academics and the rigor is still there, but it's not necessarily at the same level as where the age of the child is versus their grade level.”

More than half of Mead’s 800 students speak a language other than English at home. In addition to the Newcomer classes, the elementary school has bilingual classrooms for students who speak Spanish. It also offers traditional ESL classes for students who speak other languages but don’t have refugee status or a pathway to asylum.

“We have about 100 Newcomers in our in our campus right now, and I would say about 90% of them are Afghan refugees,” Garner-Maskill explained.

It’s a trend she said she doesn’t see changing anytime soon — about half of their Afghan Newcomers arrived this year. Students have up to two years in Newcomer classes before they’re slowly transitioned into traditional ESL classes.

Garner-Maskill said it was common for her office to be filled with three or four adults when she meets with Afghan parents — mom, dad, and whoever in the family or neighborhood speaks the best English. She said Afghan kids are accustomed to playing pretty rough with each other, and she often has to explain to parents that there are different rules at school.

“I had a conversation with a family earlier in the year. They were cousins, and they were very handsy with each other. And the dad's like, ‘It's okay.’ I'm like, ‘No, dad, not in school. It's not okay,’” Garner-Maskill said.

Northside has a district Newcomer liaison that meets with families and helps them enroll. Lately, a lot of their work has involved deciding what age their children are — and therefore what grade they should be in. Afghans don’t celebrate birthdays, so Garner-Maskill said sometimes deciding their grade can be tricky. Northside also pays for a remote interpreter service.

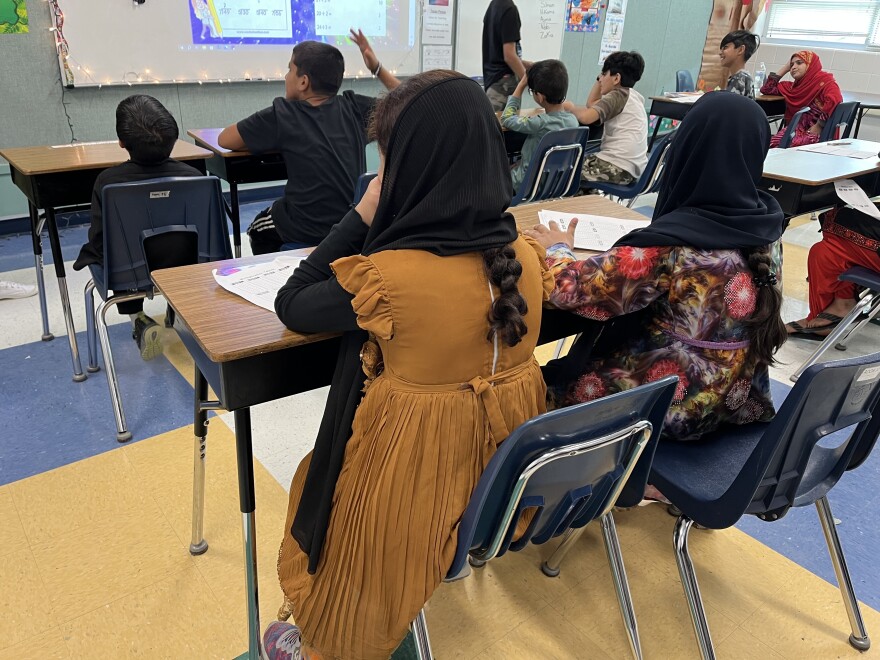

On a half day in May, Mead’s third grade Newcomer class ate lunch in their classroom before going home.

Girls in headscarves shared separate groups of desks from the boys — but all of the kids shared their favorite chips.

“Takis are the thing,” Garner-Maskill said. “It has been the phenomenon here,” agreed their teacher, Aria Pluck.

“Takis are spice,” explained one of her students with a satisfying crunch.

The students were excited to see a TPR reporter's mic and headphones — they use similar tools to practice English. The children crowded around to speak into the mic.

“Salaam alaikum,” shouted one student, as another leaned around to shout a greeting too.

Pluck was new to teaching a year and a half ago when her class enrolled at Mead as second graders. She stayed with them this year when they moved up to third grade.

Because most of her students weren’t in school before coming to the U.S. — or attended rarely — she’s teaching her students to read, in addition to teaching them English.

“Some of the first data entries that I have of their reading levels was just ... very pre-beginner [or] beginner ... and now they're just blowing me away and other teachers away. And they’re just doing so well because they’re such sponges,” Pluck said.

She’s also teaching them how to process and express their emotions — and deal with the trauma of living through war.

“Everything in their life just felt so chaotic. And so, when they come to America and when they settle in San Antonio ... suddenly it's a lot more peaceful here and things are kind of settled down,” Pluck said. “But now the peace has become itchy to them. And in order to feel comfortable, they kind of serve some chaos.”

One way she’s created order — and built up their resilience — is through a ritual of call and response.

“I am strong,” Pluck said. “I am strong,” repeated the students. “I am smart. I am important.” Then they say the words again in their native Pashto.

Pluck said she made it a priority to learn and repeat words in her students’ native Pashto that she wants to sink deep in their hearts and stick with them.

They may be learning English, but the school also wants the Afghan children to have the chance to remember — and celebrate — their native language and culture.

According to district officials, more than 1,000 Afghan immigrants have enrolled in Northside schools in the past two years. North East ISD has about 300. Both districts offer Newcomer classes at schools that have enough students with refugee or asylum status.

One of those schools in North East is Colonial Hills Elementary. The school has a long tradition of enrolling students from around the world. Half a dozen flags hang from the ceiling in the school’s lobby to celebrate that tradition.

In their combined fourth and fifth grade Newcomer class at the end of May, students took turns doing math problems on the board. Because they have fewer Afghan students, they combine the grades.

North East ISD’s Kerry Haupert helped Northside launch the Newcomer program about 15 years ago. She now oversees the program at North East.

“North East ISD had the refugees the longest, (since) they first came to San Antonio back about 2004 when we had the Sudanese and the Somali Bantus,” Haupert said. “However, we didn't start the actual Newcomer classes until about six years ago.”

Haupert said North East and Northside also offer Newcomer classes at some middle school and high schools, although the program works a little differently since students have less time to catch up — and also have to start getting class credits.

Former Northside ISD Superintendent Brian Woods saw the added challenge of supporting older refugee and asylum seekers first-hand in the early 2000s when he was principal of Clark High School.

“We would get some kids who came to us at, say, 17 years old, [with] no academic language whatsoever. And then imagine trying to get them ready to graduate in a year or two. I mean, virtually impossible,” Woods said. “And so, our goal at a secondary school, depending upon how late in the education process a child shows up to us, may be just to teach some English and some skills that can help them acquire employment after high school.”

Woods said the goal is to help students fully complete high school credits where possible. But sometimes it can be tempting for older refugee and immigrant students to leave school so they can help support their family.

“When I was at Clark, we actually did some career and technology courses purely for Newcomer students,” Woods said. “One of the ones we did, for example, was welding, because with welding and a little bit of English, you can make a really meaningful income.”

Prior to his retirement, Woods was part of discussions with San Antonio nonprofits about gaps in services Afghan families are experiencing.

“Food insecurity is one. Language acquisition — not so much for the children, but for the adults — is one, especially in a culture where women don't have as much access to education,” Woods explained. “Job training and the skills around it is clearly a need. And then there's a long-term housing need.”

The hope is that by identifying the needs, San Antonio can better meet them.

Haupert is coordinating a grant North East ISD recently received to help meet some of those needs for North East families at a welcome center.

“We provide tutoring, we provide adult ESL classes. We have a social worker, we have a case manager. We're also offering partnerships with UT Health Science Center to help with dental,” Haupert said.

The center is located near a chicken plant and a fruit plant where Haupert said some Afghan parents work.

“We want to make it a home, a community for everybody to be able to come,” Haupert added.