The story goes that Fritz Lang conceived of Metropolis on a visit to New York City in 1924. Seeing the Woolworth Building, he instantly knew what the look and feel of his next film would be. In truth, Lang had already been working on the scenario for Metropolis with his wife, Thea von Harbou. But the towering skyscrapers and brilliant lights of Jazz Age NYC gave Lang a clarity of vision.

At nearly five million marks, Metropolis was the costliest, most extravagant production ever by the German Ufa studios. And almost immediately following its 1927 German premiere, Metropolis would never be seen in its original form ever again, having been hacked apart by its American distributor, Paramount.

Efforts to restore Metropolis over the years began in earnest in the late 1960s. Although Metropolis had been largely forgotten by the public after the development of talking pictures, a generation of young film fans, soon to be directors themselves, discovered the silent epic, declaring it one of the most influential science fiction movies of all time. More than a trace of Metropolis can be seen in Ridley Scott’s futuristic Blade Runner, or George Lucas’ dystopian society of THX 1138. Heck, even Madonna freely adapted Metropolis for the David Fincher-directed “Express Yourself” music video, right down to the epigram “Without the heart there can be no understanding between the hand and the mind.” (In a winking nod to Lang, Madonna also wears a pinstriped suit and dangling monocle in the video).

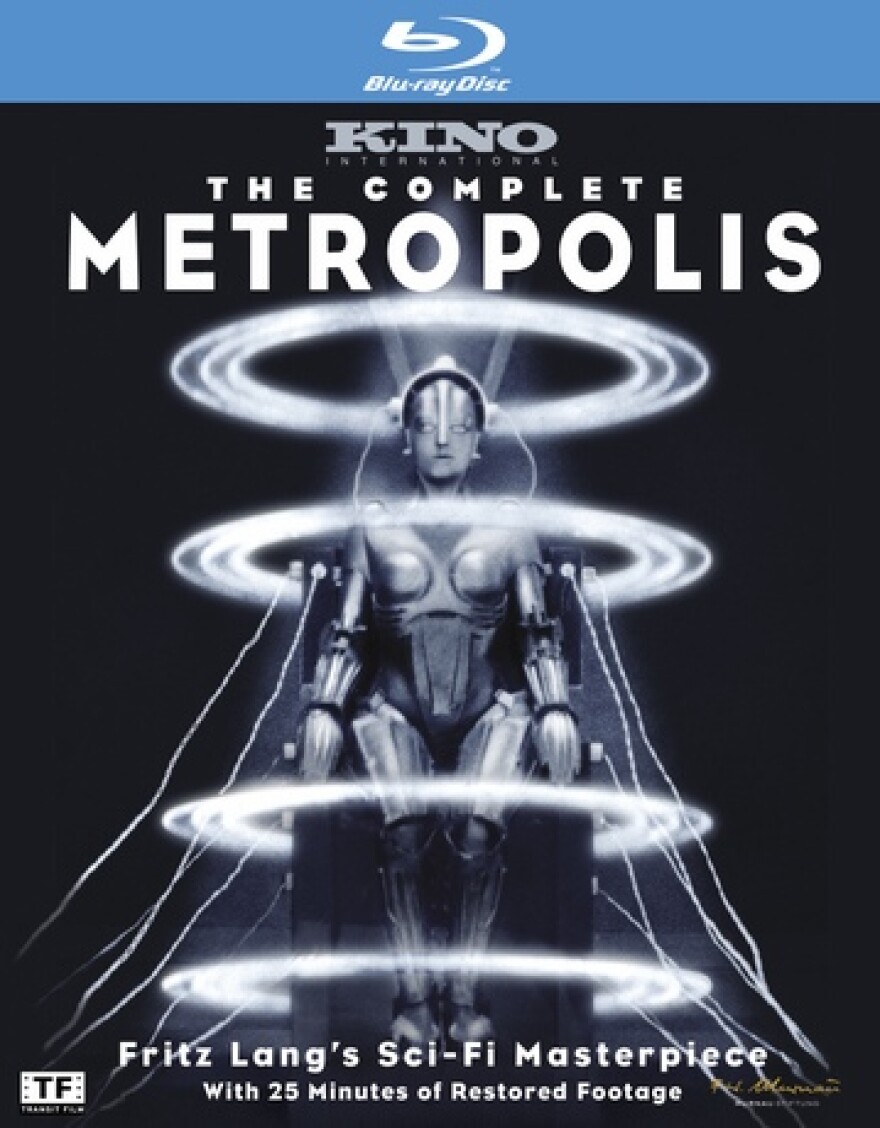

But Metropolis would remain in an incomplete form for nearly 80 years, until 2008, when a 16mm print of the near-complete version of the film was found in the archives of the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Using the best available 35mm print, and that badly damaged 16mm print, a new digital master was created, and premiered in Berlin in early 2010. Following the film’s American premiere at the Turner Classic Movies film festival in April, 2010, the film toured the country, and is now available on DVD and Blu-ray.

The movie opens in Metropolis, a city dominated by towering skyscrapers, the largest of which is the New Tower of Babel, where the city’s founder, Joh Fredersen lives in luxury. Below Fredersen and the other upper class residents of the city are the working class, toiling away at a machine that keeps the city running. Fredersen’s son chances upon a beautiful young woman, Maria, leading the workers’ children on a tour of the city’s enchanted garden, and soon learns of the deplorable conditions the workers of Metropolis face.

Meanwhile, Fredersen, having been presented with some mysterious papers found in the hands of a dead worker, consults with the scientist Rotwang. Rotwang looks every bit the part of “mad scientist.” His frizzy hair, wild eyes, erratic behavior and one rubber glove make Rotwang the model for everyone from Doc Brown (Back to the Future) to Dr. Strangelove. Rotwang tells Fredersen the papers are maps to the 2,000 year-old-catacombs beneath the city. As the two men explore the depths of Metropolis, Rotwang, still harboring a grudge against Fredersen for stealing his beloved long ago (a plot point made clearer by this restoration), schemes to use his machine-woman creation to lead the workers of the city in revolt.

The climactic scenes of Metropolis are spectacular and harrowing. Fritz Lang spared no expense. Thousands of extras panic and riot, thousands more gallons of water gush over them as they try to escape the flooding city, and in a truly diabolical, or maybe demented, move, Lang used real fire, staged really close to his lead actress, as she’s burned at the stake by an angry mob.

Metropolis belongs to that special class of silent films that retain their power to delight and astonish even in our noisy world of 2010. The visual effects, many of them created in-camera by cinematographer Karl Freund, are no less amazing than the computer-enhanced spectacles we see regularly at the multiplex. Indeed, some of the effects of the 1920s feel more “real” than CGI.

About 25 minutes of footage have been restored to Metropolis since its last restoration some 10 years ago. Reaction shots and the aforementioned subplot involving Rotwang and Fredersen’s shared love for the same woman enhance the narrative. Fredersen’s spy, known as the "Thin Man," has a larger role. And the climatic flood scene at the end of the picture is longer and more perilous than ever before.

The Complete Metropolis is accompanied by its original Gottfried Huppertz score, newly recorded for this restoration. Huppertz’ music looks back toward the 19th century harmonically, but matches the modern story well. As it turns out, the music is also what may have saved the movie for future generations. No shooting script for Metropolis exists. No records detail the cuts made to the film over the years. But one thing that did survive was Huppertz’s score for the film. By using that annotated score, and the 16mm print discovered in Buenos Aires in 2008 that prompted this latest restoration, archivists were able to assemble the most complete version of Metropolis the world has seen since 1927. Even if it were not such a thrilling historical find, this production would still be, as Roger Ebert called it, “the film event of 2010.”

THE COMPLETE METROPOLIS ON BLU-RAY & DVD

The Complete Metropolis on Blu-ray and DVD looks about as spectacular as it can, given the film’s tortured distribution history. Most of the movie looks terrific, its black-and-white presentation displaying a sharpness and contrast that you may not have seen before, especially if you only know the “Giorgio Moroder Version” from the 1980s. When footage from the 16mm source print is spliced in, defects show up on screen, including noticeable vertical scratches. The restoration team did the best digital cleanup work they could with the available material without damaging the integrity of the original image.

A 50-minute long documentary, "Voyage to Metropolis," included on the disc, details the making of and history of the restoration of the film. There’s not a whole lot of information about the film’s original production, but there are some wonderful comparison shots of futuristic 1920s architecture, such as that of Erich Mendelsohn, that inspired Lang’s design work.

A short interview with the curator of the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, Paula Felix-Didier, is also included on the disc. Ms. Felix-Didier explains how her institution came to be in possession of the only known copy of the near complete Metropolis.

One thing that’s missing that I would have loved to have on the disc is a commentary track. Metropolis’ production was immense. Fritz Lang’s direction was, by many accounts, authoritarian and dictatorial. There have been scores of essays and books written about this film, and being a silent, it lends itself naturally to a running commentary.

Still, that’s a minor quibble for what is surely one of the most exciting releases on DVD and Blu-ray this year.