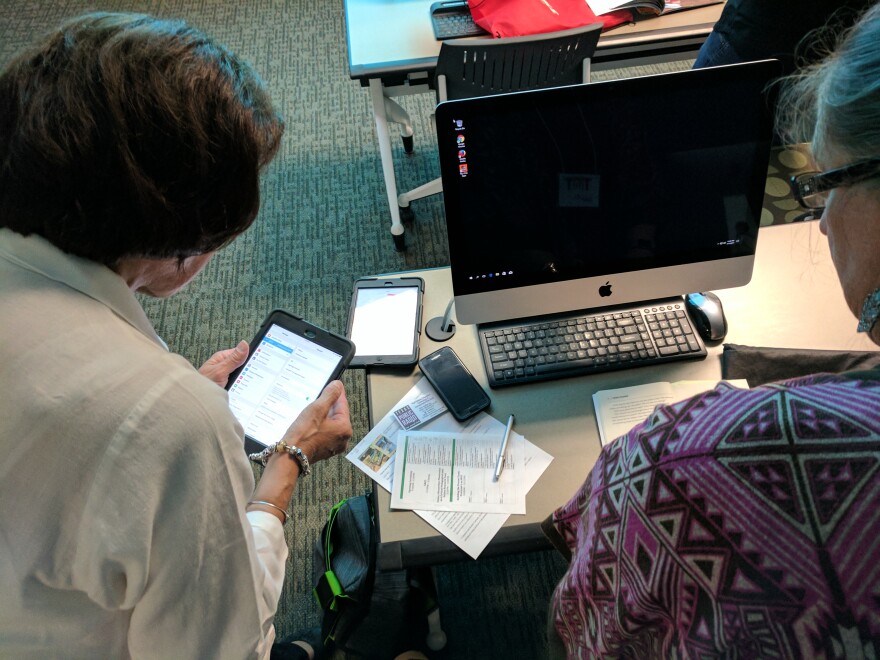

Alice Asevedo works for Edgewood Independent School District. Laura Johansen homeschools an elementary-aged child.

Both women are blown away by this training on Augmented-Reality books. AR books use smartphones or tablets to add a layer of content on traditional books.

Over their audible gasps, laughs and exclamations, there is a palpable excitement over how they can use these books.

"It's the Earth," says Johansen, "It's the whole Earth," she says staring at a three-dimensional model through an iPad.

"Oh my God," says Asevedo laughing.

"You can see the whole planet and you can rotate it and see where all the continents are," Johansen says in awe. She stops over an icon of a hurricane, hovering over the Gulf of Mexico. She clicks and more information about Hurricane Katrina pops up, eliciting another gasp.

The two are part of a 15-person training event at a recent conference at the University of Texas at San Antonio. They are looking a variety of children's books, both nonfiction and fiction, and are using provided tablets and pre-loaded apps to make them come to life.

Early childhood books are at the forefront of the AR publishing movement, says Texas A&M Kingsville Assistant Professor Marybeth Green.

"Everybody says 'wow,' and they're so enthralled by what they see that they get really excited about it," she says.

Despite that excitement, Green says teachers need to have a defined plan before bringing AR books into the classroom. There is a lot of concern about the new technology becoming a distraction.

Green ran a small study with 20 student-teachers at rural schools around Kingsville.

She says she did get feedback about AR books being a distraction, but several said AR added to comprehension. One student-teacher relayed that after multiple attempts of describing it, her students just couldn't grasp the concept of the dark side of the Moon. But one look at the augmented-reality book with a three-dimensional model, and the kids instantly got it.

Enhanced engagement was another positive her small study showed. For instance, one student responded he had never understood just how small a Tyrannosaurus Rex's arms were, "and he questioned her about why they were so short, and she suggested he go back to the book and read some more. And he dove right back into the book so that he could understand," says Green.

Green says she doesn't know of any large-scale studies around effectiveness of AR books.

Back at the training, Johansen and Asevedo are already figuring out how to use the books to teach.

"I think it would be an amazing tool for English as a Second Language," says Johansen. "To see it and see the words. To give you that immersed context (rather than) just seeing a two-dimensional picture," she says.

"I mean, it brings it to life," says Asevedo.

Just a few seats over Valorie Neff who works for the Heritage Academy holds her iPad at different angles. Nothing happens.

"Learning how to do new stuff sometimes takes practice," she says.

Neff is struggling with WiFi connectivity, with apps that don't work with different books, and with where the right place to put the iPad is.

"I'm sure there is a trick to it," she says with a chuckle.

But her difficulties aren't keeping her from seeing the possibilities for her work with children suffering from autism.

"They would be trying to catch it," she says referring to a dragon flying across her screen, "and it would do a lot for them with their fine motors as well as encouraging their reading,"

This is the first training with AR books that UTSA's Ilna Colemere has offered, and she is excited about the response, especially the critical feedback. WiFi connections that don't work, she says, are things that happen in real classrooms.

"How does that impact how these books are used?" she asks. "How will students react? Are they going to continue? Are they going to get frustrated? Are they going to persist?"

Colemere thinks if the books grab kids the way they do the teachers, students will persist.