This report originally aired on Texas Matters in November 2008.

Among the splendors of Texas is the music that has sprung from its roots. Texas music is as diverse as its people. Texas tunes include jazz, spirituals, gospel, rock 'n' roll, Tex-Mex, Cajun, Hillbilly, the music of Czechs, Germans and other European immigrants. And then there is the blues.

As American Southerners settled in Texas they brought their slaves with them. The singing of African-Americans as they worked long, hot hours on farms and plantations became a part of the larger culture. Black musicians sometimes played for whites, who listened or danced. And the minstrel show, consisting of musical and comedy numbers, became very popular after the Civil War.

Black music in Texas, as elsewhere, retained some African characteristics, such as the use of polyrhythms, call-and-response patterns of singing and playing and the use of bent or slurred tones known as "blue notes." The field hollers and work songs of slavery were African also in that they were often sung by people working together and reflected a collective effort and consciousness.

But after Emancipation, a new individual consciousness was reflected in the music called the blues, often played by a lone man accompanying himself on a guitar.

No one really knows where or when the blues began, but it was widespread through the South and much of Texas by the turn of the 20th century. Generally a performer would sing a line, repeat it, then close the stanza with a rhyming line that often contained an ironic twist. Though this 12-bar form became the most common, eight- and 16-bar blues also existed.

Recordings of older musicians from the 1920s provide evidence of what early blues and other late-19th-century forms were like. Henry "Ragtime Texas" Thomas, born in Gladewater about 1875, recorded when he was in his 50s, singing and playing the guitar and a wind instrument called the quills, or panpipes. One of his songs, "Fishing Blues," has been recorded by, among others, the 1960s rock band the Lovin' Spoonful.

Another such songster – one whose repertoire ranged from blues to ballads, dance tunes and religious songs – was Mance Lipscomb. The son of a country fiddler, he was born near Navasota in 1895. After working most of his life as a sharecropper, he was discovered by the folk-music crowd in the 1960s and enjoyed considerable popularity in the last years of his life.

Also a significant figure was Huddie Ledbetter. "Leadbelly," as he was popularly known, was born in 1889 on the Louisiana side of Caddo Lake, which lies on the border of northeast Texas and northwest Louisiana. Leadbelly spent much of his life in Texas, in and out of prison.

Through the efforts of Texas folklorists John and Alan Lomax, Leadbelly left a rich legacy of recordings that, like Lipscomb's, cover a wide range of styles. He is best known for popularizing "Good Night, Irene," which, with somewhat sanitized lyrics, has become a pop standard.

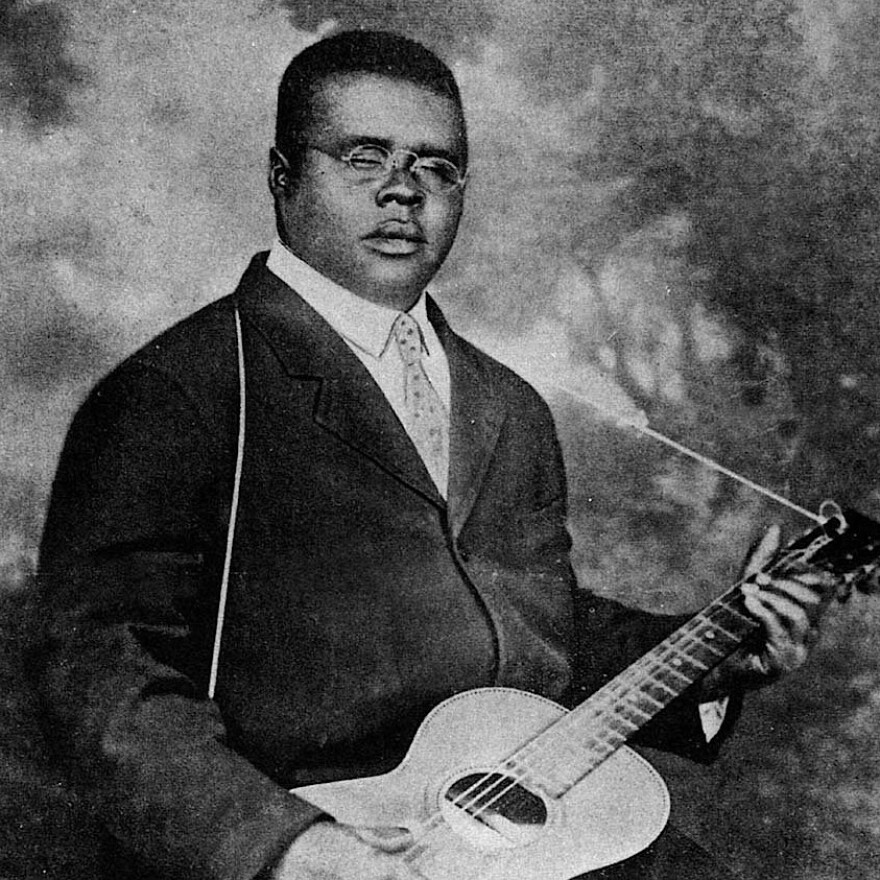

After moving to the Dallas area around 1912, Leadbelly found his primary instrument, the 12-string guitar, and learned much about the blues from Blind Lemon Jefferson, who later became the first country blues recording star. Born in the farm community of Couchman 70 miles south of Dallas in 1893, the young Jefferson walked the roads around his home, playing for money on the streets and in the cafes and joints of the surrounding towns. He spent time in Mexia, where the local strip of black businesses was known as the Beat, playing both alone and in a string band with other musicians.

Jefferson was certainly not the only such musician in the area. Blind Willie Johnson was in Dallas about the same time and made his first records there. And there were strolling string bands that played a wide repertoire ranging from blues to pop tunes. One such group, the Dallas String Band, included bass player Marco Washington, stepfather of future bluesman Aaron "T-Bone" Walker.

Jefferson attracted the attention of a Paramount record scout, thanks to the efforts of a local record-store and shine-stand owner named R.T. Ashford. From 1926 until 1929, Jefferson made regular trips to Chicago to record and achieved considerably popularity in the "race" market – records marketed exclusively to African-Americans. In addition to blues, he recorded a few spirituals under the name Deacon L.J. Bates.

Blind Lemon Jefferson died in Chicago in December 1929. Apparently he froze to death, though the circumstances of his death have never been fully explained. But his brief career exerted considerable influence on many performers who followed. One of his songs, "Matchbox Blues," was recorded years later by both rockabilly star Carl Perkins and the Beatles. He was buried in Wortham, and a marker erected years later pays tribute to him and his influence.

Jefferson's success opened the door to a flood of country blues recordings by a number of artists, including Texan "Little Hat" Jones, Alger "Texas" Alexander and J.T. "Funny Papa" Smith. Blind Lemon's dexterous guitar style featured single-string runs and unconventional phrasing – what one musician called "suspended time."

This style was a major influence on T-Bone Walker and other blues players who, starting in the mid-'30s, played the new electric guitar. Amplification allowed the instrument, once consigned to the rhythm section of a large band, to become a solo instrument. Walker's style of playing lead guitar in a call-and-response pattern with an orchestra came to define a whole school of post-World War II blues, though he didn't really achieve star status until he moved to the West Coast in the 1940s.

An earthier strain of blues was exemplified by Sam "Lightnin' " Hopkins of Centerville, who was a child when he met Jefferson at a church picnic. Hopkins spent most of his life in Houston, playing an amplified version of the down-home East Texas music he had grown up with.

Texas had a strong tradition of piano blues, too, hard-hitting music with strong elements of ragtime, the music popularized by composers such as Texarkana-born Scott Joplin. Texas piano blues developed in the rough lumber and turpentine camps of East Texas and in the honky-tonks of Dallas' Deep Ellum and Houston's Third, Fourth and Fifth Wards, in places with names like Mud Alley and The Vamp.

Robert Shaw, a member of the "Santa Fe" group of pianists named for the railroad, survived into old age running a barbecue business and grocery store in Austin, and, like Mance Lipscomb, had a late second career playing for white fans.

Another link to the past was Dallas pianist and singer "Whistlin" Alex Moore, who continued to perform up to the time of his death in 1989, at age 89.

Texas-born musicians played a major role in the development of the electric guitar. In addition to T-Bone Walker, these innovators included Eddie Durham, who played with Buster Smith in the Blue Devils, and Charlie Christian, of Benny Goodman's band.

Perhaps the most idiosyncratic and controversial jazz musician to come out of Texas is alto sax player Ornette Coleman, who began in Fort Worth rhythm-and-blues bands and went on to invent a radically new music called free jazz, with his own theory of collective improvisation, called "harmolodics." Such developments indicate the power and complexity beneath the apparently simple music with roots in slavery.

SOURCED FROM http://texasalmanac.com/topics/culture/texas-music-its-roots-its-evolution