What is rarer than a shooting star?

Rarer than a diamond?

Rarer than any metal, any mineral, so rare that if you scan the entire earth, all six million billion billion kilos or 13,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 pounds of our planet, you would find only one ounce of it?

What is so rare it has never been seen directly, because if you could get enough of it together, it would self-vaporize from its own radioactive heat?

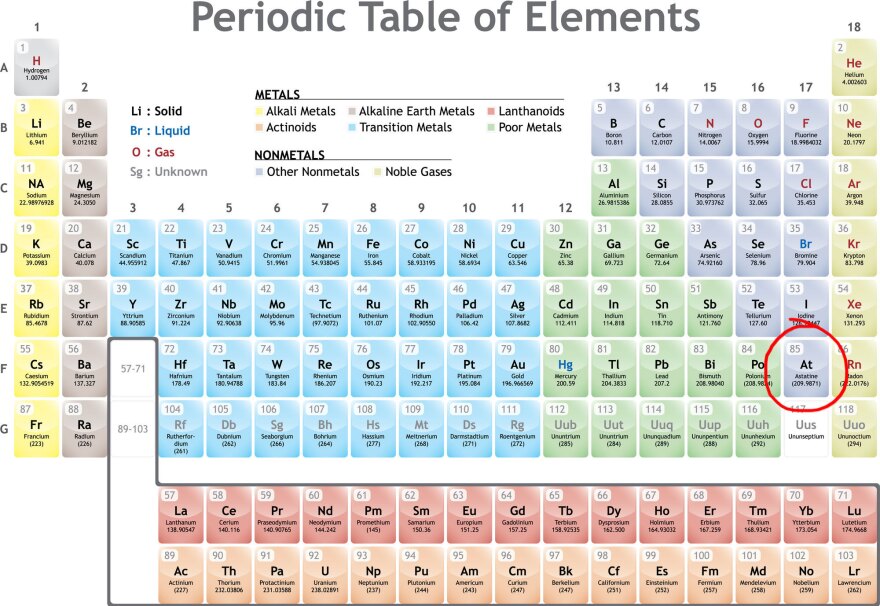

What is this stuff that can't be seen or found? Well, here's a hint. It's sitting modestly in a lower row in the Periodic Table, down on the lower right, in a box marked "At."

"At" stands for astatine. It is an element with 85 protons packed into its nucleus, thus the atomic number "85" ...

The problem is, there's something about 85 protons in a tight space that nature doesn't enjoy. Almost as soon as they squeeze together bits of nuclear material get spat out, or get added, and poof! It isn't astatine any longer.

This element has a half life of roughly 8 hours, meaning if you could get a clump of it to stay on a table (you can't), half of it would disintegrate in 8 hours, and then every 8 hours another half would go until in a few days, there'd be no astatine on the table. Its nickname should be "Goodbye!"

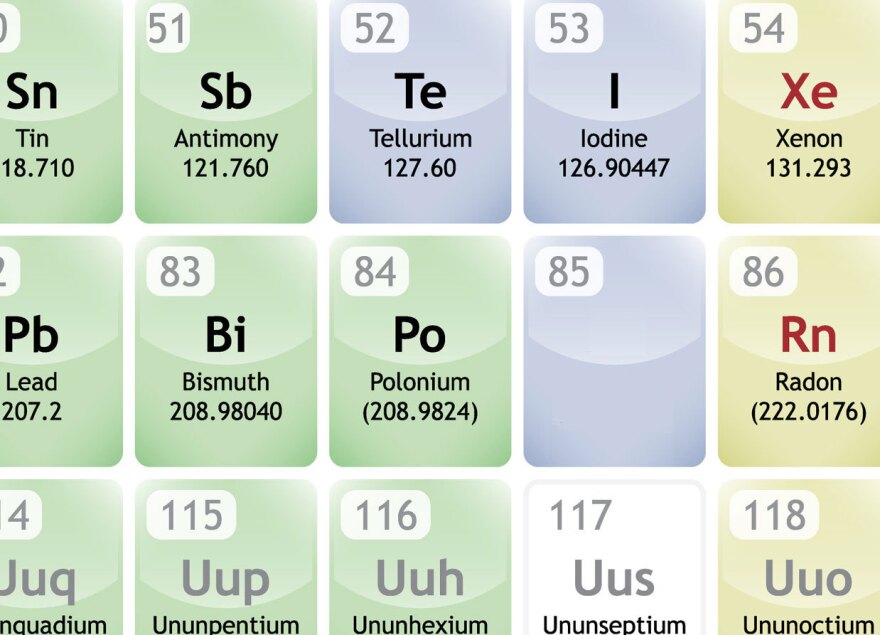

By comparison, a clump of bismuth (atomic number 83) loses half its atoms in 20 billion billion years. So astatine blinks out fast. Its name comes from the Greek "astastos" meaning "unstable."

How Do You Know It's There?

How do you discover something you can't see and can't find? Well, according to science writer (and Radiolab regular) Sam Kean, you believe it should be there, and it will come.

In his book The Disappearing Spoon Sam explains that when the periodic table was being assembled, nobody had seen an atom with 85 protons, but — because the 85 box is directly below the Iodine box ("I" — atomic number 53) ...

... they figured, when it turns up, it might resemble iodine. Elements sharing a vertical column often share behaviors. What's more, they figured heavier atoms might be made to disintegrate and become astatine (however briefly). Or lighter atoms could be made weightier. So thinking it would show up, in the 1930s lots of physicists tried to make some "element 85."

Alabamine! Dakkin! Helvetia!

In 1931, an Alabama physicist said, "I've done it!" and he called his discovery "alabamine" (discoverers get naming rights), but his work was invalidated. A chemist in Dacca (now Bangladesh, then India) said "I've got it!" and named his version "dakkin", but his method proved faulty. A Swiss chemist came next and called his discovery "helvetium" from Helvetia, (Latin for Switzerland), but nobody could reproduce what he'd done, until finally three Berkeley scientists did it right, and so it became Astatine.

Check The Rodent ...

A few years later, some lab-created astatine was injected into a guinea pig and traces were found in the little rodent's thyroid gland, which is where you'd normally find iodine!So the element did behave like its upstairs neighbor! Now they were sure. "Astatine remains the only element whose discovery was confirmed by a nonprimate," writes Sam.

Alma Mater-izing

But with all this place-naming, I wondered, why didn't the Berkeley scientists name their element after Berkeley?

Well, Sam reports, scientists at UC Berkeley discovered so many elements in the 40s and 50s, they could be patient. Element 85 is astatine. Element 97 iscalled berkelium. Element 98 is called Californium. These discoveries led The New Yorker to muse that if only they'd waited longer they could have spelled out their complete name ...

... the university ... has lost forever the chance of immortalizing itself in the atomic tables with some such sequence as universitium (97), ofium (98), californium(99), berkelium(100).

Berkeley scientists Glenn Seaborg and Albert Ghiorso quickly wrote back to point out if they'd done "universitium" "ofium" they'd have been in dangerous territory. What if some NYU scientists found elements 99 and 100 and named them "newium and yorkium"? Then Berkeley would have handed NYU a four-element crown.

The New Yorker staff, rooting for the home team, warmed to the challenge: "We are already at work in our office laboratories on 'newium' and 'yorkium,' they wrote back. "So far we have just have the names."

Ah, the vanities of science!

Some of you will say that another element, francium (atomic number 87), is even more unstable than astatine, and you're right. Its nickname should be "gone!" As Sam writes, "If you had a million atoms of the longest-lived type of astatine, half of them would disintegrate in 400 minutes. A similar sample of francium would hang on for 20 minutes. Francium is so fragile, it's basically useless." Astatine, however, is rarer and can be used to treat thyroid cancers.

For a more official version of Astatine's discovery, here's a synopsis from Chemistry World:

Astatine was the second synthetic element to be conclusively identified just three years after Technetium, was isolated by Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segre of the University of Palermo. The element had actually been created in a cyclotron particle accelerator at the University of California in Berkeley where Segre spent the following summer continuing his research. But miles away from Italy Mussolini's government passed anti Semitic laws which barred Jewish people like Segre from holding University positions; so he stayed where he was, taking up a job at Berkeley and in 1940 he helped to discover Astatine along with Dale Corson, he was then a post doc and later went on to become President of Cornell University and grant student Kenneth MacKenzie. They bombarded a sheet of bismuth metal, that's two doors down from Astatine in the periodic table, with alpha particle to produce Astatine 211, which has a half life of about 7 1/2 hours and it neatly filled the gap in the periodic table just beneath iodine. Segre went on to become a group leader for the Manhattan project which built the first atomic weapon. And it was only once the Second World War was over that the trio proposed the name Astatine for their elemental discovery. It was from the Greek word meaning unstable.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))