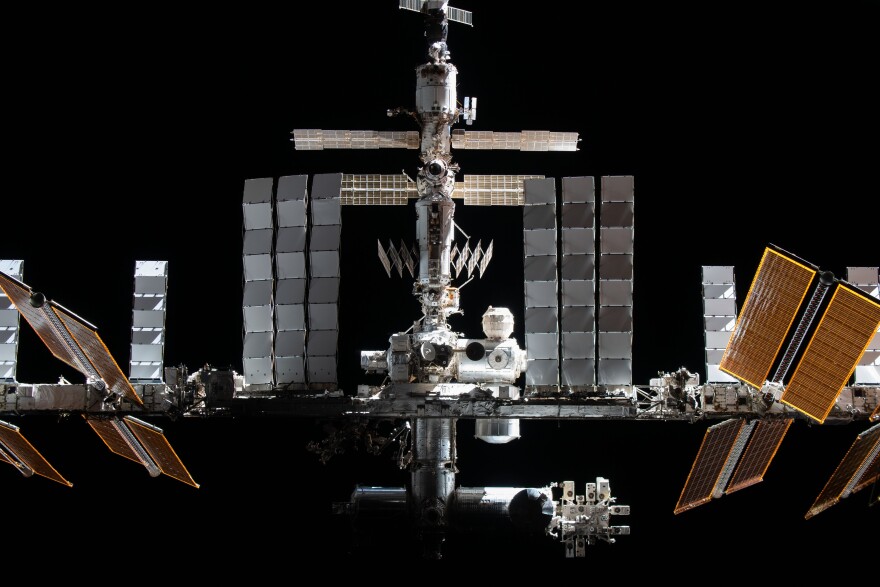

The first component of the International Space Station was launched in 1998. It's a collaboration between NASA and four other space agencies around the world. The ISS is scheduled to end its operational life in 2030, and there's the problem with what to do with the giant station after it's abandoned. NASA has selected a private company to deorbit the space station when it's finished its mission. On this week’s edition of Weekend Insight, TPR’s Jerry Clayton spoke with space expert Chris Combs, The Dee Howard endowed Associate Professor in aerodynamics in the UTSA Department of Mechanical Engineering.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Clayton: Those of us who are enamored with the International Space Station, don't even like to think about the end of it. But I guess it's inevitable, right?

Combs: I think while there are some sort of maybe pipe dream ideas to boost the space station up to some very, very high orbit where it could essentially hang out as a museum indefinitely. It sounds like that would require so much thrust; it's probably not something we should really entertain right now. However, other space stations have been deorbited.

So usually, this is some sort of semi-controlled reentry where you do the best you can. You try and direct it towards the Pacific Ocean. And really, you hope everything burns up as best as and as long as it can. But the space station is about the biggest thing we've ever tried to do this with. It makes it a slightly more complex problem, which is why NASA solicited proposals for a deorbit vehicle, and that was just recently awarded to SpaceX.

Clayton: Back in the day, I remember all the hoopla around Skylab, when it finally came back to Earth. Can you remember what happened back then?

Combs: SKYLAB was a partially controlled reentry. Basically, what they did was sort of at the last moment, as this was getting pretty low into orbit. NASA adjusted the orientation with its thrusters to try and direct this into as much of an unpopulated area as possible. But it was not the same type of planned operation that we ended up with that we're going to have for the International Space Station. And so this ended up with components that came down in the vicinity of Australia, which, for whatever reason, tends to seem to be a magnet for this type of thing. And there were some pretty large fragments that did survive reentry.

Clayton: As you mentioned, SpaceX has been selected to build a deorbit vehicle, what are their plans? And how's this all going to work?

Combs: So unfortunately, we don't know a lot right now. And SpaceX notoriously, doesn't tend to provide a lot of information that they don't necessarily want to. NASA hasn't given us a ton of details, but speculation is that there's going to be some variant of their Dragon spacecraft that they're going to use to help control this reentry. And basically, in essence, steer the space station down into the Pacific Ocean as best as possible.