Sign up for TPR Today, Texas Public Radio's newsletter that brings our top stories to your inbox each morning.

During his full-throttle push to pass private school vouchers this legislative session, Gov. Greg Abbott repeatedly painted a rosy picture of the state’s public school system.

“Public education funding is at an all-time high. Funding per student is at an all-time high,” said Abbott during his State of the State address earlier this year, where he designated “school choice” an emergency item for the 2025 legislative session. “Improving education requires more than just spending money.”

After years pushing for the change, Abbott recently celebrated victory in that fight. Earlier this month, he signed into law a bill that creates a program allowing parents to use public funds toward private education through state-managed education savings accounts. Texas is set to spend $1 billion on these school vouchers during the program’s first two years.

Meanwhile, with just weeks left on the clock before the Texas Legislature gavels out on June 2, a bill increasing funding for public schools is nowhere near the finish line.

Throughout this legislative session, the governor's official Facebook page has pushed a prolific campaign in favor of school vouchers, largely based on the claim that public school funding is already at an all-time high.

One post claiming to separate “school choice” myths from facts repeatedly proclaimed that “the average funding per student in public schools is over $15,000.”

The governor’s office posted the same graphic on eight separate occasions between February and April.

On another eight occasions, Abbott’s office posted a graphic claiming “public education funding is at an all-time high of $85 billion.”

Both statements, while technically and numerically true, are misleading.

That’s according to best practices on measuring school finance as explained to TPR by multiple experts and according to a TPR analysis of state data that compared three methods of calculating per-student funding.

The analysis and conversations with experts revealed that both claims use numbers, math and averages that distort the actual impact felt by most public schools in Texas. The numbers ignore rising costs due to inflation and include all of the money distributed by the Texas Education Agency — even though a substantial part of that TEA funding is not used for the day-to-day operation of schools.

The figures pushed by Abbott’s office are also based on data from the 2022-2023 school year, when school districts still had access to unprecedented amounts of temporary federal money allocated to help academic recovery following the COVID-19 pandemic. That temporary federal money has now dried up.

“Per-student funding is at an all-time high and anyone claiming otherwise is deliberately misleading Texans,” said Andrew Mahaleris, the governor’s press secretary, in an emailed statement responding to TPR's analysis.

“Governor Abbott has provided more funding for public education than any Texas governor and signed into law one of the biggest teacher pay raises in our state’s history,” Mahaleris added. “Since Governor Abbott took office, Texas has increased funding to more than $70 billion, an all-time high according to the Texas Education Agency.”

The document Mahaleris linked to in his emailed statement (included above) lists the agency’s total annual funding for the 2022-2023 school year as $85.33 billion, which comes out to $15,503 each for the 5.52 million students enrolled in Texas public schools that year.

However, that same report made clear that, when adjusted for inflation, the $85.33 billion total funding is not a record breaking all-time high per student. It stated that, when adjusted for inflation, total funding per student was about the same in 2023 as it was in 2020: $12,140 in 2022-2023 and $12,113 in 2019-2020.

In his emailed response to TPR’s request for comment, Mahaleris also pointed to the same TEA report as proof that, “even after adjusting for inflation, 2023 was still the year with the highest funding, with an inflation-adjusted increase of 23% since Governor Abbott took office.”

Page 11 of that report did find a 23% increase in total inflation-adjusted funding in FY 2023 compared to FY 2014. But that same page also shows total inflation-adjusted funding increased by less than 1% between FY 2020 and FY 2023. And FY 2023’s number was shored up by federal COVID dollars that weren’t available in FY 2020 — and were mostly spent by FY 2025.

Measuring an upward or downward trend is largely dependent on what years are included.

Pages 11 and 12 of the report do not include calculations for this year or last year, stating that the data is not yet available. While final data for the two most recent years is not available, preliminary data is. TEA also chose to include that preliminary data on page 5 of the report, ending in FY 2025 instead of FY 2023. Ending with FY 2023 would have shown a decline in revenue.

Pages 3-5 of the report lists the state and local funding provided to Texas public schools for operational expenses like salaries, utilities, and instructional materials. Page 5 shows that schools received $11 more per student in weighted average daily attendance in FY 2014 than in FY 2023 when adjusted for inflation. By FY 2025, TEA was able to report a 1% increase compared to FY 2014.

Texas calls the state’s funding formula for operational expenses the Foundation Schools Program, or FSP. FSP determines how much money schools get by multiplying the basic allotment by the weighted average daily attendance, or WADA.

The basic allotment is the minimum amount allocated per student in Texas public schools. “Weighted average daily attendance” is determined by combining a school’s attendance and characteristics of the students and the school. Weights are added to the attendance if students have higher levels of need — like being low-income — and if schools are more expensive to operate because they are small. (The weights make WADA much higher than enrollment: 7.2 million instead of 5.5 million in 2023.)

The funding amounts used by the governor in various social media posts, listed on pages 11 and 12 of the TEA report, include all of the revenue that both TEA and the state’s public schools receive, including federal funding for school lunches, and local bond money that can only be used for construction.

Mahaleris said the governor’s office chose to use total funding instead of just the funding available to operate schools “because that is the most accurate reflection of state spending on public education.”

However, total funding includes more than just state spending. It also includes federal and local revenue.

“Pensions, administrative costs, school breakfast and lunch, and debt are all educational costs,” Mahaleris said in the email.

Total revenue vs operating expenses

School finance experts told TPR that total revenue can be a valid way to measure school funding, but it needs to be put in context, and the sources of the revenue need to be clear.

“The best practice, more than anything, is to be clear about what it is that you are reporting,” said Bruce Baker, a University of Miami professor who researches education policy and finance.

“The taxpayer has equal interest in both the revenue that's raised and where it's coming from and how and on whom it's spent,” Baker said. “We can test it out different ways, but just tell me what’s in there.”

“In my opinion, it is not unreasonable for the governor to be talking about total revenue,” said Lori Taylor, head of the department of public service and administration at Texas A&M University-College Station.

“But it needs to be understood that that includes the payment of debt and the construction revenues, and that that can be very lumpy and a problematic metric to compare across districts,” Taylor added.

In his February State of the State address, Abbott did not make the sources of revenue he was pointing to clear. He simply said that “public education funding” and “funding per student” are “at an all-time high.”

Additionally, Abbott’s speech — and the graphics on the governor’s Facebook page — don’t specify the year he’s referencing.

One graphic — purporting to be fact checking how much money public schools get per student — lists the basic allotment separately from local property taxes, even though funding for the basic allotment comes from a combination of state money and local property taxes.

That graphic also lumps together both the Maintenance & Operations property tax and the Interest & Sinking property tax without making it clear that they are local funds — or that only one of the two kinds of property tax can be used to operate schools. The Interest & Sinking tax rate can only be used to pay back debts accrued building and renovating schools.

In an email, Mahaleris pushed back against any assertion that the graphic is misleading.

“The graphic does not misrepresent funding, it addresses common myths by showing how the basic allotment is only a portion of total per student funding,” he said in his response to TPR.

Taylor told TPR it’s not uncommon to measure all of a school district’s revenue, including funding to pay back debts for construction, in part because other states don’t track revenue for debts as clearly as Texas does. But, for that same reason, Taylor said experts often prefer to look at spending instead of revenue.

“It can be somewhat difficult to separate out the revenues for interest or repayment of debt and revenues from construction compared to other revenues,” Taylor said. “So that's why you'll get a very different picture when you talk about revenues than when you talk about expenditures.”

“It’s basically what comparison are you trying to make? What are you trying to understand?” she added. “If you're trying to understand the revenues that are available to a school district, the total revenues that include Interest & Sinking is going to be somewhat misleading.”

Baker agreed.

“If you want to go to the next step of looking at what do the dollars translate to in terms of the student performance and outcomes, we should really be trying to focus on the dollars spent on the programs and services that serve the students that are currently there right now,” he said.

TEA vs LBB

Public school advocates have been calling for an increase in the basic allotment since the 2023 legislative session. They say that increasing the basic allotment is the best way to combat the rising cost of education caused by inflation, since it is the number the state funding formula uses to calculate how much money schools get.

The basic allotment hasn’t been increased since 2019, before the pandemic hit and before inflation soared.

“Nobody's saying that funding per student is ($6,160). That is what the basic allotment is. And that is the building block of the formulas,” said Chandra Villanueva, director of policy and advocacy at the progressive think tank Every Texan.

“Most people understand that that's not the total per student amount. So, this whole post of his is very disingenuous,” she added.

Villanueva said she prefers to look at how much money is being spent in the classroom when she looks at per student funding. For that reason, she favors the analysis provided by the Legislative Budget Board, the agency that breaks down the financial impact of bills for state lawmakers.

“To get to $15,000 per student, you basically need to take everything that's in the budget, not just money that goes to the classroom, but all of the money to administer TEA, any kind of grant program, anything like that,” Villanueva said. “So, it is a very, very unrealistic amount of money.”

The Legislative Budget Board (LBB), reports a nearly $10 billion drop in Texas Education Agency funding in 2025 compared to 2020 when adjusted for inflation. That puts per student funding at $12,170 for the 2024-2025 school year — just $8,099 per student when adjusted for inflation.

According to TEA Commissioner Mike Morath, LBB’s calculations differ from TEA’s because LBB does not include funding for pensions or for bonds to pay for construction, and because TEA and LBB calculate inflation differently. LBB also reported the entire $12.4 billion in federal ESSER III funds in the 2020-2021 school year, while TEA split the temporary federal COVID recovery dollars across several years beginning in 2021-2022, when the first ESSER III dollars reached districts.

Villanueva sees even the LBB’s numbers as slightly inflated. They include $4 billion allocated to schools in 2023 that were never spent because Abbott refused to sign a bill increasing school funding unless lawmakers first passed vouchers.

And both TEA and LBB’s numbers are based on statewide calculations, not a measurement of how much most districts receive.

“We have really tiny districts that are funded at a very high rate, because it costs a lot more to run a very tiny district,” Villanueva said. “There's definitely districts out there that are skewing this average.”

Texas also has a handful of small districts with a lot of property wealth that consistently have three or four times the state average in funding per student, because of a policy TPR reported on in 2023 called Golden Pennies.

According to a TPR analysis of district-level school finance data that removed small districts and districts with unusual amounts of Golden Pennies, the average General Fund total was $11,143 per student for the 2024-2025 school year.

In Texas, a district’s General Fund includes the state, local, and federal revenue used for operating expenses.

Because most students attend larger school districts, that analysis accounts for 91% of the students enrolled in Texas public schools.

TPR’s average district-level per student amount, $11,143, is about a thousand dollars less than the LBB’s statewide average.

More money on the way?

Regardless of how you calculate the numbers, public school administrators, advocates, and researchers agree that school districts need a substantial increase in the basic allotment to catch up with inflation. At least $1,000 more — $1,400 by some measurements.

More than 80% of school districts will need to make budget cuts next school year, and 63% think they will end the current school year in a deficit, according to a survey from the Texas Association of School Business Officials.

According to an analysis by Taylor, the basic allotment needs to increase by 18% to $7,256 to keep up with inflation — an increase of $1,096. She based that analysis on the employment cost index from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“That is probably the best way of thinking about such a labor-intensive industry as education,” Taylor said. “You want to understand the purchasing power of school districts, and 80% of what they spend their money on is personnel.”

Mahaleris made a point of mentioning legislation that could increase funding for public schools in his statement to TPR.

“This session, Texas will invest a record of more than $8 billion in additional funding into public education to support our students and teachers as they help us build a brighter future for all Texans,” he said.

House Bill 2 includes about $8 billion in new public education funding, including a $395 increase in the basic allotment. But the bill has only made it halfway through the legislative process, and the end of the legislative session is only a few weeks away. The ticking clock worries public education advocates.

“The House and the Senate are very, very far away on school funding, and the Senate did not put this amount of money in their budget,” Villanueva said. “Are they going to even hear it? Are they going to just sub out their language from SB 26 which is just a teacher pay bill and doesn't have any of the other elements?”

Senate Bill 26 includes about $4 billion in new funding to increase teacher pay, but it doesn’t increase per student funding.

Abbott made increasing teacher pay an emergency item this session, but did not prioritize public school funding.

Villanueva said advocates like her are really frustrated by a decision by House Public Education Committee Chair Brad Buckley to replace the House’s voucher proposal, House Bill 3, with the Senate voucher bill, Senate Bill 2.

“Representative Buckley kept saying that we're going to pass [the voucher and school funding] bills together, we're going to move these bills together,” Villanueva said. “It was a huge betrayal when he substituted out HB 3 for SB 2. That was a signal that we may not get anything at all for school finance. That the absolute priority was moving the voucher bill.”

The House passed both the voucher bill and public education funding bill on the same day. But because the Senate had already approved their own voucher bill, it was able to concur with the changes the House had made — sending the legislation directly to Abbott’s desk.

Meanwhile, the public school funding bill, HB 2, still needs to be taken up by the Senate.

“[Rep. Buckley] took out several steps in the legislative process when he substituted in [the Senate voucher bill],” Villanueva said. “There was no reason for him to give it the SB number and cut out so many steps and lose any leverage that we had on the school finance fight.”

However, Senate Education Committee chair Brandon Creighton said on X on Thursday that leaders in both chambers were making progress on getting House Bill 2 across the finish line.

“Senate and House Education leaders are now in the sixth day of negotiations on HB 2, a bill that would deliver historic levels of funding for Texas public education and teachers,” Creighton posted.

🚨🚨🚨 Education Update 🚨🚨🚨

— Brandon Creighton (@CreightonForTX) May 7, 2025

Senate and House Education leaders are now in the sixth day of negotiations on HB 2, a bill that would deliver historic levels of funding for Texas public education and teachers. These discussions are fundamental to our commitment to ensuring Texas…

Republican leadership’s characterization of House Bill 2 as historic or “record-breaking” also does not account for inflation.

But even just a $395 increase in the basic allotment will help financially struggling school districts. In recent years, districts across the state have laid off staff, closed schools, and increased class sizes in a bid to shrink their budgets.

Even before inflation put districts into crisis, Texas public schools were underfunded, according to Baker from the University of Miami.

“Texas was probably at its peak of adequate and equitable funding sometime between 1998 and 2004, and it's been a downhill slide ever since,” he explained.

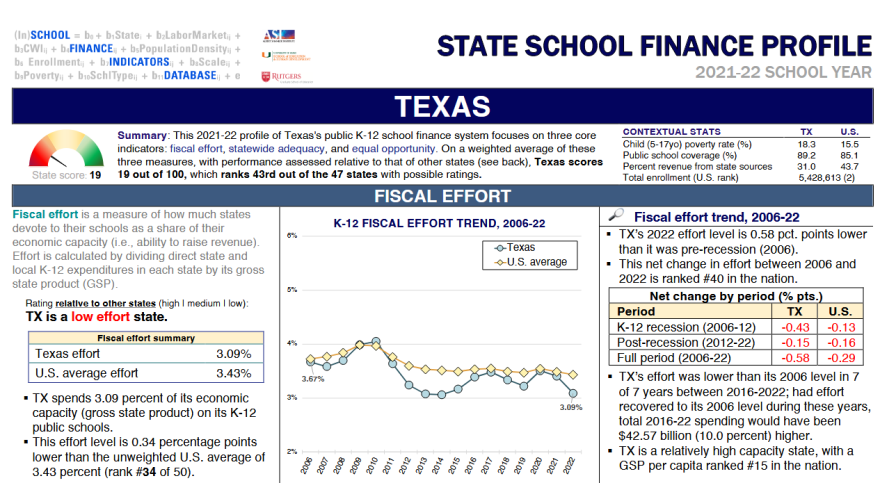

To better put public school funding into context, Baker looked at how much of a state’s economic capacity is dedicated to schools.

According to his analysis, Texas ranks 34th in the country when it comes to how much of the state’s economic capacity is spent on public education, spending just 3.09% of its gross state product on public schools.

Still, Baker said Texas has one thing going for it that many red states don’t.

“Historically … Texas has had some more interest and pride in the maintenance of a higher quality and more equitable public education system than some of the other states in the deep red zone, including my own,” Baker said. “At least public school finance is still a major part of the legislative conversation.”