For many Texans, colonias evoke images of mismatched shanties, dusty roads and children wading through excrement-rich floodwaters after heavy rainfall. That’s also how people who testified before Congress in the 1980s described these unofficial neighborhoods.

Despite significant progress to improve living conditions in colonias over the last four decades, these settlements are still defined by their worst moments.

But that’s not the whole picture.

“I think that it's also an American success story, the development of colonias,” said Francisco Guajardo, CEO of the Museum of South Texas History.

He spent much of his childhood in a colonia, and he finds the prominent narrative tired and reductive.

“I am not going to poverty-pimp the colonia idea, because enough people have. And I think that that's been to the psychological detriment, of a lot of us,” he said.

While the public’s attention on colonias has largely centered on squalor and societal neglect, Guajardo said there’s more to their story.

Colonias resulted from unwanted farmland

“The story of colonias in South Texas is really something that predates the war, meaning World War II, but it does not become pronounced until after the war,” Guajardo said.

In the early 20th century, developers promoted the agricultural potential of the Rio Grande Valley to Midwestern growers. They touted the mild climate, abundant water sources and fertile soil. Farmers flocked to the Valley.

“People were lulled into believing that this was this huge garden of prosperity,” Guajardo explained.

For decades, the region had a booming citrus industry with acres of oranges and grapefruits covering the flat floodlands.

The promise of work summoned a labor force composed mostly of Mexican immigrants or Mexican Americans.

But prosperity was fickle. The climate, which had first enticed growers, bred insects and diseases, which hurt crops and diminished yields. Also, extreme weather events could ruin a harvest.

“It began to not be this garden of prosperity into the 1960s and into the 1970s,” Guajardo said.

Many of these problems hit smaller farmers particularly hard because they did not have the resources to withstand the damage done to their crops. Just after the war, a series of freezes ended their desire to keep growing.

Many landowners wanted out of agriculture in the Valley, and so they started selling their properties. Laborers were eager to buy.

“You also have a lot of working people who don't have a lot of income, and they're attempting to reach their American Dream. ... They want their piece of land,” Guajardo said.

Landowners capitalized on this demand. Before selling the land, they stripped and sold the fertile topsoil, which made the area even more flood-prone.

Then they subdivided the land into residential plots and sold them without infrastructure for cheap prices to those low-income workers attempting to realize their American Dream. Thus, colonias were born.

“Maybe you can come up with $1,000 to buy a quarter acre in this startup neighborhood that doesn't have running water, doesn't have electricity and doesn't have paved roads. And so, those are the colonias,” Guajardo said.

Some sellers, to quell weariness over the lack of infrastructure, falsely promised that these services were on their way.

Because many buyers didn’t have enough cash and their credit was often too poor to finance their purchase, they’d sign contracts that made it so one missed payment could result in foreclosure. These contracts also withheld the deed from residents until they paid off the property in full.

Other times, sales happened under the table, so purchasers had no legal claim to their property.

Still, colonias made homeownership a possibility for many low-income families, and through time, these close-knit communities became beacons for change.

Residents move in

From the 1960s to the 1980s, colonia development peaked not only in the Valley but all along the U.S.-Mexico border.

In the mid-1970s, Guajardo’s family was priced out of public housing, and they decided to move into a new colonia outside of the city of Elsa.

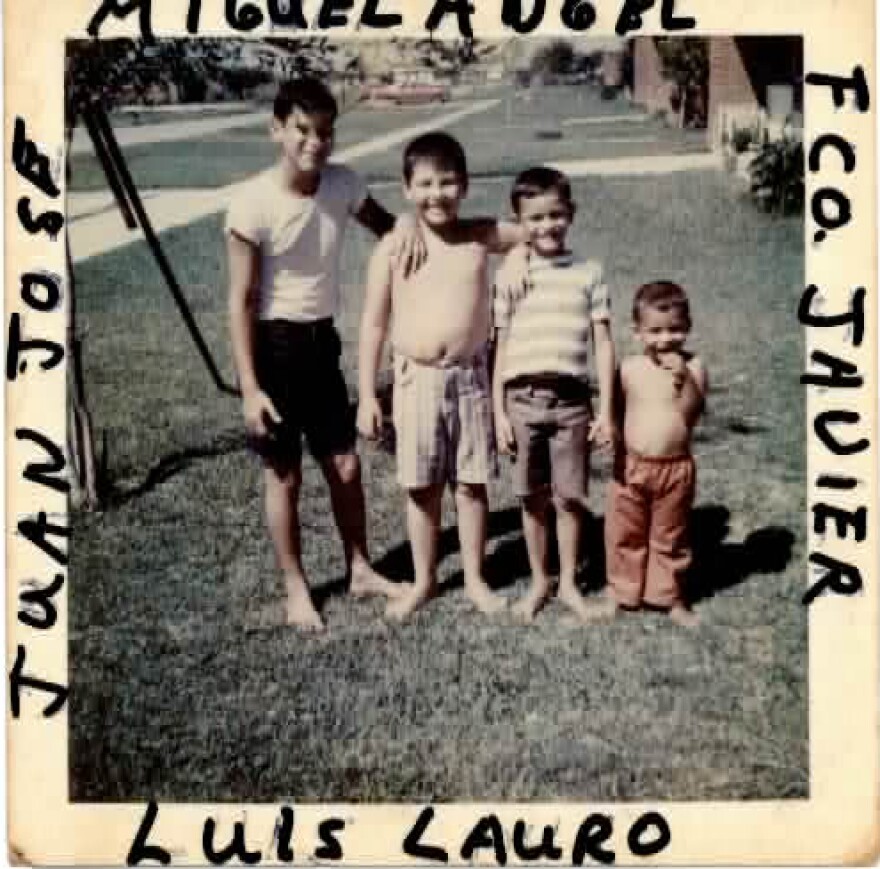

Like many others, Guajardo’s family set out to build a home the only way they could afford to — piecemeal and slowly.

His family settled temporarily in a trailer home while they built their house. To make money for construction supplies, Guajardo and his brothers traveled to other states, like California, to work on farms as migrant laborers.

And it wasn’t just a house they had to build. Like thousands of other colonia residents, they also had to build their own utilities.

They created ditches to install their water pipes and dug holes for their septic tank.

It was hard work, but the family was not alone. Improving the neighborhood was a collaborative endeavor.

“Other people are moving in as well. And so we're all like sharing in the same sort of electricity, like completely rigged,” Guajardo said. “It was like the most beautiful thing, because it's like resilience, ingenuity, and all of this.”

In need of building expertise, Guajardo’s father sent his older brother to carpentry school. After completing the program, his brother became the colonia’s resident carpentry expert.

“It took a while but we built a house,” Guajardo said.

But that was far from the only hurdle. Colonias were located in rural county areas, not within city limits.

There were no water services, drainage systems or street requirements that are usually mandated by cities and paid for through city taxes.

Colonias’ lack of basic infrastructure and poverty rates, rarely seen in the United States at the time, resulted in neighborhoods where living conditions were dismal.

“Middle school for me and then high school was in a colonia. Elementary school was in the federal housing projects. No comparison. Federal housing was like the Taj Mahal,” Guajardo said.

But eventually, cities began annexing many colonias. In some cases, clusters of colonias became their own municipalities.

Colonias also started banding together to ask their public officials for basic needs.

“That's what your taxes are supposed to be for — for basic infrastructure. So really, all you're doing is you are asking for what is right, which is 'I contribute to this community. You public officials — would you please contribute to my neighborhood so that my truck won't always be needing new tires?,' ” Guajardo said.

They had small wins. Individual colonias and organizations were often able to get infrastructure improvements through incessant pleading and public outcry.

When existing water systems wouldn’t serve them, they created their own, which still exist today.

But it wasn’t until the 1980s that the federal government took action.

Congressman Kika de la Garza of South Texas led the initial charge for changes to colonias at the federal level. He faced some resistance when he presented his proposal to provide federal aid to colonia communities.

At the hearing, Congressman Joseph Kennedy II said other lawmakers worried that helping colonias would promote illegal immigration.

But the bill passed, and it still assists with installing first-time infrastructures and improving existing ones.

Because of De La Garza’s advocacy in the 1980s, the federal government released a first-of-its-kind report that assessed conditions in these areas.

The report found that around 200,000 Texas residents lived in 824 colonias in 1990. Only 60% had water, and only 1% had sewage systems.

Unsurprisingly, rates of diseases like Hepatitis A and tuberculosis were double that of the rest of the state.

Today, colonias are still found along the U.S.-Mexico border, with the highest concentration in Texas. In 2018, an estimated half a million people lived in more than 2,000 colonias along the state’s border.

While conditions have vastly improved, many still struggle with the same problems. But Guajardo said fixating on the negative only overshadows colonia residents’ strides and successes.

“Hay mucha gente necesitada en las colonias todavía, no question about that. But the colonias are also places of hope. And I think that's the point,” he said.

When he looks back on his life in the colonia, he doesn’t dwell on suffering or helplessness because, for him, this isn’t the legacy of living in a colonia.

Rather, he thinks of progress, tenacity and the tireless resolve that turned that bare plot of land into a home.

“You can't build a house if you don't have the land. And the effort, the idea, the vision, the hope, the dream of the land is really the magic,” Guajardo said.

This reporting is supported by the Pulitzer Center.