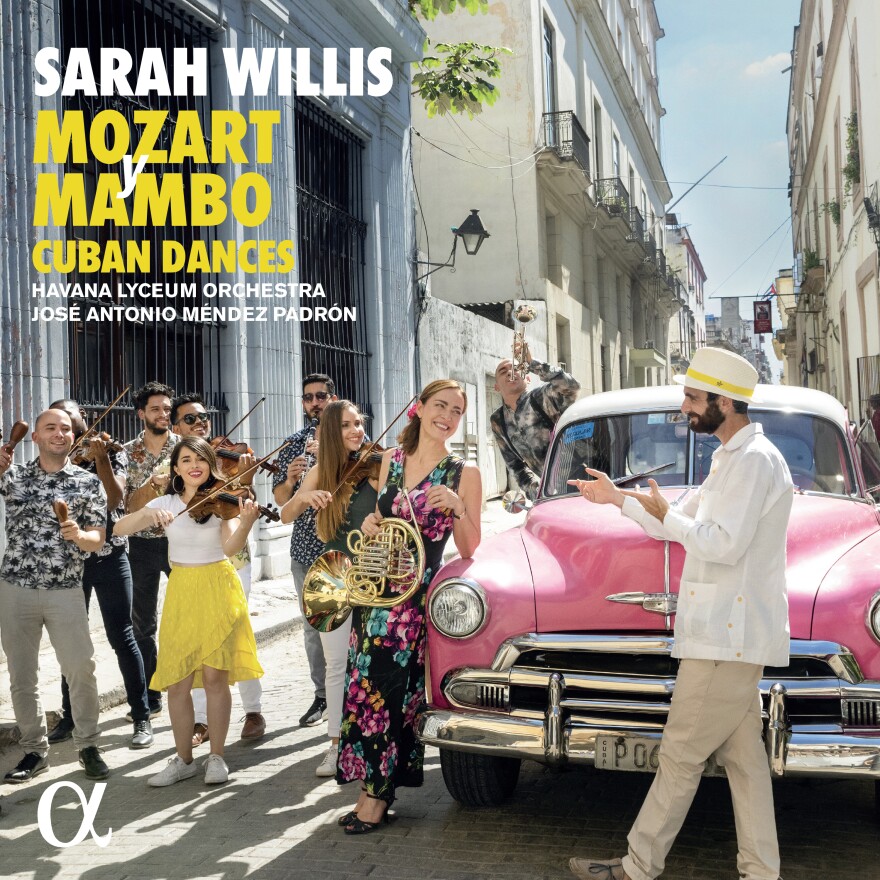

To look at the photograph which dresses the latest of Sarah Willis' explorations of “Mozart y Mambo: Cuban Dances,” one might be amazed at the smiles, the “alegria,” on the faces of the musicians. And when one hears the Havana Lyceum Orchestra play on what is now the second in a series of recordings by Ms. Willis with the orchestra and their conductor Pepe Mendez, it's fair to ask how such dedication to music-making can come out of one of the most impoverished countries in Latin-America?

“It hurts my heart that it's like that, and I will do everything I can to support my Cuban musicians.”

She explains that "Mozart y Mambo" became more than just a musical mission. “[It] has become much more than just an album. It's now this big project. My Instruments for Cuba Fund, which we set up to be able to buy new instruments and strings for the violins and reeds for the clarinets and some percussion instruments, just because they can't get them . . .wonderfully generous people have been donating instruments for us and we've been taking them over to Cuba when we go.”

At the same time, Sarah Willis, a twenty year veteran with the Berlin Philharmonic, has long had a dream of one day recording Mozart's four horn concerti.

“I was just waiting for the right moment to do it,” says Willis, as she retells a story she loves to tell, of how there has come to be a second “Mozart y Mambo” album. “There's plenty of really great chamber orchestras around the world that I thought maybe here, maybe there, but the day I met the Havana Lyceum Orchestra I suddenly thought – wouldn't it be a crazy thing to do it in Cuba?”

There were plenty of obstacles, ranging from where in Havana to record, and how to make a church sound like a great concert hall. Willis recruited some of the same producers and sound engineers who ensure the Berlin Philharmonic sounds, well, like the Berlin Phil. They are both skilled and patient.

“We did have a little bit of a problem with animals during the recording! Once there was a bird who got in during the day and didn't want to go to sleep and kept flying around and screeching. And if you listen very closely to the album, on one particular track, you can hear the little cricket that made our lives a living disaster for many moments.”

Through it all, the musical mission of a second “Mozart y Mambo” moved forward and has now realized fruition. “Mozart y Mambo: Cuban Dances” is now available worldwide. It is testament to both the talent and determination of a dedicated group of Cuban musicians and their soloist, Sarah Willis.

Explains Willis, “For a Cuban, music is in their DNA. It's not something they play for a hobby like, like we maybe do or play for a job, it is in their bodies. And if they are not able to express that, it's very, very sad.” She continues, “I went to Cuba quite a few times, during the pandemic. I was there three times and completely locked down. And it was tough, but it was just something, it was a natural progression, we just had to finish this project in Cuba.”

James Baker, host of KPAC's Classics a la Carte, recently spoke to Sarah Willis about the release of “Mozart y Mambo, Part 2 (Cuban Dances).” You can listen to the audio using the player at the top of this page, or read the transcript below.

James Baker: Before we talk about "Mozart y Mambo: Cuban Dances," I think our listeners would be interested in where you are now, where you might have been within the last several days, and where you might be tomorrow. In other words, what's it like to tour with the Berlin Philharmonic in the big leagues?

Sarah Willis: Yeah, yes. Well, we're on our big beginning of season tour. It's always the same places that we visit, we have an opening concert for the season in Berlin. And then we traveled to Salzburg, and then to Lucerne, and sometimes Paris. But this time, we're going to the London Proms . . . we do that every two years, which of course makes my mother very happy.

JB: What are you going to be doing [when the album releases]? Are you going to be dancing in the streets?

SW: Oh, I've done so much dancing in the streets over these past two years while preparing "Mozart y Mambo." I'll actually be on a plane to London. And I will land in London and I will be picked up by my sister and my six year old nephew, who's my biggest fan, and we're planning to go to Hyde Park, and celebrate the release of the album ourselves. So it's literally been the last two years of my life. And so to have my family around me, the day it comes out, is going to be very special.

JB: Well, let's set things up for part two by going back and reflecting for a moment on part one of "Mozart y Mambo." Whose idea was that and who made that project happen?

SW: Who do you think? It was my crazy idea, I've always wanted to record the Mozart horn concertos, and was just waiting for the right moment to do it. And of course, there's plenty of really great chamber orchestras around the world that I thought, okay, maybe here, maybe there. But the day I met the Havana Lyceum Orchestra, and the day I heard them play Mozart, I suddenly thought, wouldn't it be a crazy thing to do it in Cuba? And of course, everyone said, "Are you crazy? You can't make it happen." And look at us! You know, two years later, we're on part two already. It's been, I must say, one of the biggest challenges of my life, not only horn playing wise, but also organizing wise, this part two all appeared, or has been worked on, all during the pandemic. It's basically what has given us all hope, and something to work for during the pandemic. And it's been, it's been an incredible amount of hard work, but I think one of the most exciting and fulfilling projects of my life, if not the most exciting.

JB: I recall in part one, you rushed the release just a little bit, if I'm remembering correctly, because we didn't know what our future was with the pandemic beginning to take hold. And so I think you told me that you released it a little bit earlier than you'd intended. But it certainly did not hurt its popularity. I think it rose to number one on some of the charts.

SW: It rose to number one on a lot of the charts here in Germany. It was number one for months, it was really the most incredible thing. And you're right. We did get it out pretty quickly. We recorded in January, and we had it out by June. And this time, we're doing pretty well. We recorded it in April, and it's now September, so we're doing pretty well on the on the production point of view. So thanks to Alpha Classics for that.

JB: Some say that the follow up to an album is sometimes a hard sell, but I can't imagine "Mozart y Mambo, Part Two" being a hard sell at all. It's such a terrific recording.

SW: Well, thank you so much for saying that. I'm very excited about it. But you're absolutely right. A Part Two is always a challenge. I mean, just look at all the movies, the part twos I mean it doesn't matter how good they are. They're still always Part twos. But what we tried to do on the second part of "Mozart y Mambo," which we call Cuban Dances, is include something different, a different element and our different element this time is an original work. And on this album you have the very first horn concerto to come out of Cuba, this is really something so exciting for me. And so we've included this original original work, right, right next, sandwiched in between the two Mozart horn concertos we've included. And, of course, you have some old favorites. Our wonderful arranger Jorge Aragón, has done two incredible arrangements. And there's a little nod to Mozart at the very end, which I'm sure you heard, and I hope it made you laugh with the pa-pa-pa.

JB: I have to tell you that I wish you had been sitting here with me as I listened to the recording for the first time. Because I laughed out loud on a number of occasions . . . yes, on a number of occasions, and Oh, yeah, you just charmed me and amazed me with your virtuosity. It was such a pleasure to listen to. And I'm sure that Mozart would be very proud of this as well. He was such a jokester, and there are so many little musical jokes that will make every listener laugh, that are included in the Cuban numbers that you do. It's a very nice balance. And I'm sure it was all by intention.

SW: It was all by intention. Because that's really basically my intention with music in general is to make people smile and enjoy and have a good time and also to come up with something a little bit unusual. Because you know, of course, I could have recorded all four Mozart horn concertos on one album, like most people do. And that's a very tidy, very good way of doing it. But no, I have to go and mix it with Cuban music. And that made my life more difficult but so much more enriched because it's been such a fantastic journey.

JB: Now, the Cuban horn concerto that you mentioned, did you always intend for it to be sort of a . . . I hate to say it because it sounds like a diminutive, but I don't intend it that way . . . a work by committee almost, although there's individuality with every one of the movements. Did you always intend to do it that way?

SW: I actually didn't have an intention at all. I just wanted someone to write something for me, which was an original work because as a horn player, I mean, it would make me incredibly happy to know that future generations of horn players are playing a piece which I commissioned . . . I think that would really be amazing. So what I actually did was make a little competition. And I put out the word in Cuba, I said, Guys, I'm looking for a young composer to write a horn concerto for me, if anyone's interested, they can submit one minute of music for horn, strings and percussion. And I'd like it to be based on some of the dance rhythms in Cuba. And we had so many amazing, amazing entries that yeah, the horn concerto by one Cuban composer has turned into a suite of six dances by six composers. And, and it's been an incredible challenge because these six dances are traditional Cuban rhythms but completely original orchestration, melodies. It's something Cuban music has not had before. And this is changing the bar line in Cuba for writing for the horn. The French horn is not such a well known instrument over there. So it's it's been quite a challenge also for me, because these rhythms are not only the rhythms we know like cha cha cha and mambo. We've got rhythms that you've probably never even heard of either like Changüí and Guaguancó, and the Danzon, the national dance of Cuba. It's been really, really a huge undertaking, but there were too many good entries and I just couldn't say no.

JB: Well, they're all so delightful and entertaining in different ways. There are some that have a certain mood, kind of an introspective mood. There's always heart on the sleeve, though, and I know that you embrace that in your playing, don't you?

SW: I try to, I mean, I've said many times before, I'm not a true soloist. And my job is to play in the section of the Berlin Philharmonic, and I much prefer to sit behind the orchestra than stand in front of the orchestra. But for this project, and also to help promote my beloved Cuban musicians, I had to get in front of the orchestra and play these pieces. And it's been a big challenge for me to do that because I you know, if you're used to playing tutti in the back row, suddenly to be the soloist, it takes not only a lot of practice technically but to emotionally as well to actually get the courage to go and stand up there. But yeah, heart on your sleeve is really good way of putting it. I couldn't do it any other way. And when you hear the Bolero, which is the third, the fourth movement of the horn concerto, and for me, it's just heartbreakingly beautiful. And there's no other way to play it than with your heart on your sleeve.

JB: You know, some of these reminded me of a couple of American horn players, whom I'm sure you know, one would be John Barrows, who always played with such big heart, and there were several times that I was reminded as I listened of the recently deceased Vincent DeRosa, because there was such a lyricism and one who was willing to invest in playing music in a popular style. I love that you did that. And I would imagine that in the back of your mind, at least you were remembering Vincent De Rosa.

SW: Well, Vince DeRosa was such a character and I don't go into a recording thinking I have to play like this person, I have to do it like this I, on purpose I try not to listen to too many recordings of the Mozart horn concertos before I record it, because otherwise, I would just think, okay, I might as well forget it. There's so many good recordings out there. But Vince is such, or was . . . rest in peace, he really was the most incredible horn player and I think he's influenced so many of us and even the people that don't know who he is have heard him play because he was literally in on every soundtrack you can imagine, and has played with so many fantastic singers, like Frank Sinatra, and a lot of other people. So yes, he was a very big influence for all of all of us on players. But I go into a recording trying to make my own way, you know, but I think my own way is a lot of little influences with a lot of other people along the way. I think that's how we grow as musicians.

JB: Mozart's second concerto is such a great piece of writing, and it was said that it was Dennis Brain's favorite. Does it rank similarly for you or . . . I guess a safe answer would be to say to the question what is your favorite Mozart concerto you would have to say . . . well, all four.

SW: Yes, that would be that would be the answer, like which is your favorite child or which is a favorite color. I mean, these are difficult questions where you can't say because you love them all the same, or there's just such a big choice, I don't mean the children, I mean, the colors, that it's hard to pick one. Mozart horn concertos, they are all very individual, but they all have their completely different style. And I started the Mozart remember project with Concerto Number three on the first album, and I thought that was my favorite, because it's considered more of a low horn concerto. It's very romantic. It's very lyrical. And musically, it was quite a challenge. But I really have to say, having recorded one and two now on the second album, I loved playing number two so much. For me, it's the most dance like of all the concertos. Number one is beautiful, but it's in D major, which means it's a little fiddly for us horn players, and always remains a bit of a challenge. But number two was a pure joy. And number two, there's a lot of interaction between the orchestra and the soloist as well. I often play very beautiful high lines with the violins. And I must say this has really turned into my favorite concerto. But if you asked me when I play Mozart four, it might turn into my concerto too. It's very hard to say.

JB: Yeah, well, I was happy to see your comments about the first concerto, being in D major presenting, you know, our fingers are challenged whenever we try to play that . . .

SW: yeah, it's really a tricky little one.

JB: In some ways, it's the most difficult, for me anyhow. But I love number two and number four . . .

SW: and the good thing IS, you know, number four, have you seen that on the first or the second album yet?

JB: No. So Oh, you're teasing us?

SW: Now. I wonder where we're going to put number four.

JB: Well, I was wondering whenever you set out to do part one, if there was always an intention of doing a part two, or were you going to wait and see how things went? Or did you all along . . . I know you were building these around the Mozart concerti so perhaps you laid the groundwork and you said well, we have to go ahead and do number two and then we have to do a third album.

SW: Well, interesting enough, and this is of course a big secret (so you won't tell anyone will you?), interestingly enough that it was always planned to record the horn concertos on different albums but it was not planned to do them all in Cuba. And but when I was thinking okay, maybe I could go to Brazil or to Japan and you know, make up some and learn about some different styles of music and this is something I definitely will still do. But after the success of the first album I just thought (my record company as well) we just thought we are just not done with Cuba yet. We love it there. We love our musicians. We love how they play. I love Cuban music with a passion, as you know. But also, Cuba is in a really difficult state right now, after the pandemic, during the pandemic, was very difficult for everyone now, with the war and everything that it's a really difficult time in Cuba. And I just felt very strongly two years ago, when we made this decision to continue the project in Cuba. that I just couldn't, couldn't leave not yet. And, and I really wanted to continue this collaboration, and it gave us all hope in the pandemic, Cuba had shut down. Can you imagine Cuba with no live music, there were no tourists there. So there was no live music, there were no concerts. And for a Cuban music is in their DNA, it's not something they play for a hobby like, like we maybe do or play for a job, it is in their bodies. And if they are not able to express that, it's very, very sad. And I went to Cuba quite a few times, during the pandemic. I was there three times and completely locked down. And, and it was it was tough, but it was just something, it was a natural progression, we just had to finish this project in Cuba.

JB: You have told me before that you never arrive in Havana empty-handed. You are always bring strings or reeds, even percussion instruments. Your generosity towards the musicians you work with is as heartwarming as it is heartbreaking that this island country, Cuba, so near the US, the richest country in the world, is so in need of so many essentials.

SW: It hurts my heart that it's like that, and I will do everything I can to support my Cuban musicians. The first album actually raised money in my Instruments for Cuba Fund, which we set up to be able to buy new instruments and strings for the violins and reeds for the clarinets and some percussion instruments, just because they can't get them, as you say, so wonderfully generous people have been donating instruments as well for us and we've been taking them over to Cuba when we go and there's been a lot of support for the program, and I'm very, very grateful for that. And this will, of course, continue as long as I'm alive, at least I will do my very best. And so "Mozart y Mambo" has become much more than just an album, it's now this big project. And it really is heartbreaking that they are so close to the richest country in the world, and that they are so in need right now, to be honest, when I go when I go there, I bring more food than anything else, because it's really difficult to get anything, is really so impossible for them. It's heartbreaking. But the great thing about Cubans and my musicians, the ones that I know is that it doesn't matter how difficult times are, when they play music, they still smile, and they make you just feel like they're having just the best time and it's very special.

JB: Oh yeah, the allegria shows and especially in the videos that you put out, those are so uplifting and they really make you want to go out and dance. In relation to your instrument donation fund, we really have to mention, I'll mention, that Queen Elizabeth recently recognized you as a Master of the British Empire. How does it feel to append the letters MBE to your name? I saw it on the album.

SW: It's a great honor. It really is. I mean MBE? If you'd say that to a Brit, then of course everybody knows what it is. If you say that to someone else outside of England, they probably have no idea but it's an award, a title, that Queen Elizabeth bestows on members of the public who have done something which she considers is great for the country. And I was recognized for the services to charity and the promotion of classical music. And I went to Windsor Castle in June and got the award from Prince Charles. So it was really terribly exciting, my mother almost passed out from excitement, she was allowed to come with me. And it's a great honor, but I feel like it's for all of us because I think this Cuba project had a lot to do with it because there was a lot of publicity around it. And, and it's wonderful that classical music has been recognized like that.

JB: Well tell us about the phrase. If you can't dance it, you can't play it.

SW: Well, six dances. Okay, so you think that's fine. That's no problem, nice dances. But I was really struggling with some of the articulations. The composers had never written for horn, like I mentioned, so they were just writing down notes on a page. And I said, Guys, you've got to put accents and lines and dynamics in there because I didn't grow up with this music and I can't do it naturally. You know, if I see a line of notes, I'll go “Tata-Tata-Tah,” and they went “bobbidi-boo,” you know, they just do that automatically. So I was really struggling a few months before the recording, and I was in the Philharmonie in Berlin, with one of the composers from Cuba, Yuniet Lombida. He's written the Danzón and the Sarahchá, and he was he was in Germany at the time, and I was with him in the Philharmonie to help me work through this and he said to me, you know . . . he listened for a bit and he said, you've gotta dance it. I said, but I can't dance. These dances, they're too complicated. And I'm quite a good salsa dancer, but something like Changüí or Guaguancó And he was like, no, no, no, no. So we turned up the music really loud in this practice room and I literally the next three months I spent learning to dance these rhythms. And it made, it just it was a game changer. The minute I could feel these different rhythms in my body and where the different beats are . . . the Cubans have the Cuban music clave, which means that the beat, the time, and it changes all the time. And every single one of these pieces has a different clave. If you feel it in your body, it's easier to play. And that was a real game changer. So this is the motto of the album. If you can't dance it, you can't play it, but it's to be taken with a pinch of salt it's a little bit British humor. You know, if you can't dance it, you can still try playing it.

JB: I have one more thing I want to ask you. I know you have a busy day . . .

SW: Bruckner is calling I have to go . . .

JB: Yes. Bruckner four. You mentioned in the notes, late night recording sessions, and there was spontaneous dancing when the last take of Guaguancó was finished at 2am. Why were you doing these sessions late at night? Was it because of outside noises or . . . ?

SW: That's exactly right. I tell you after this week of recording, I was like jet lagged, because we started the recording sessions about 10 o'clock at night with sound checks. We were recording in a church in central Havana, which has an exit right out onto the street. As you can imagine, Cuban streets are not very quiet, especially at night. You have music, you have people dancing, you have dogs fighting, you have people selling things very loudly, people selling bread at 11 o'clock at night. Crazy, really crazy. So it was virtually impossible to start recording before about 11 p.m. So our recording sessions went to two or three in the morning. And then of course, we were on such a buzz with all this incredible music that we couldn't sleep. So it completely changed the body clock for the week that we were recording. But it was a very special recording. And we did have a little bit of a problem with animals during the recording. Once there was a bird who got in during the day and didn't want to go to sleep and kept flying around and screeching. And if you listen very closely to the album, on one particular track, you can hear the little cricket that made our lives a living disaster for many moments during the recording because this little cricket would start to sing about 1 a.m. And we couldn't find him. The church had very high walls. But we worked out, if you went and banged on one part of the wall it would stop for about 15 minutes. So whenever it started, we have to send someone to stand there and bang on the wall to stop this cricket and we knew we had about 20 minutes before he started again. And we managed to record most of it. But if you listen very carefully, maybe your listeners will spot the moment and where you can still hear him, he's on the recording there somewhere . . .

JB: I'm gonna present them with that challenge. Well, I know that you have a busy day ahead of you. Best of luck with Bruckner for it's such a great piece for the horns to play. And best of luck with everything with the rollout of the album. And thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us.

SW: Well, thank you so much for the lovely questions. And I just could talk about Cuba and my musicians all day, and it's been such a pleasure, and I'm going to go off and play Bruckner with a feeling of mambo inside. Thanks. Take care. Bye bye!

The new album from Sarah Willis and the Havana Lyceum Orchestra, "Mozart y Mambo: Cuban Dances," is out now.