Many San Antonians drive daily by a park that, even in its ragged state, is breathtaking, and magical. That 5 acres is called Miraflores, and the man who created it remains one of Texas’ most mysterious characters.

“I think he's a beautiful enigma,” said writer and UTSA Honors College teacher John Phillip Santos on Aureliano Urrutia. “The daring and the audacity that Urrutia brought to this story is really kind of unparalleled. I'm hoping Elise's book is going to help spark a renewal of curiosity about this legacy.”

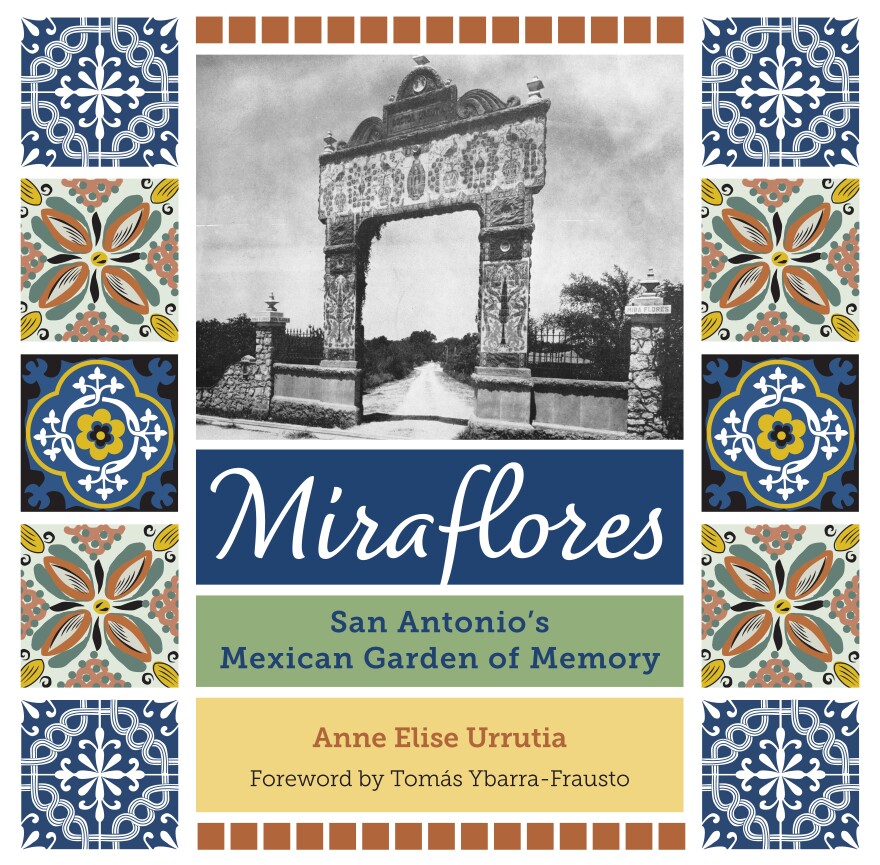

Elise is Anne Elise Urrutia — Dr. Urrutia’s great granddaughter. And the book she’s written is Miraflores: San Antonio's Mexican Garden of Memory, from Trinity University Press. She said that Urrutia’s incredible life began in a Mexico City suburb in what is now a World Heritage site.

“At the time Xochimilco was a small area probably of about 12,000 people in 1900. He was born in 1872,” Elise said. “It is a unique town because it has a canal system and that's how they moved produce around when they were farming the land.”

Urrutia was primarily of Native American descent, which was not ever an advantage since 1519, when Spain invaded Mexico and dominated the culture. John Phillip Santos said over time the friction between races softened.

“In Mexico, what emerged was called by one Mexican philosopher, Jose Vasconcelos the Raza Cosmica, the cosmic race. A mingling of all peoples of the world,” Santos said.

As it turned out for Urrutia, his timing was good. By the late 1800s those of native blood were beginning to be allowed avenues to advance themselves.

“The Mexican revolution, the period of the early 20th century, we saw this overturning of that legacy,” Santos said. “And suddenly Mexicans celebrated their mestizaje — their mixedness.”

Elise said that the young Urrutia was a gifted student.

“And it turned out that he was a really smart kid and he was able to work his way into being accepted at a very prestigious high school that was in Mexico City,” she said. “He also did very well at that school, caught the eye of the president of Mexico at the time because he graduated — not only at the top of his class — but at the top of all high school classes in the nation of Mexico.”

That president was Porfirio Diaz, who sponsored Urrutia’s entry into the Army and Medical School. Diaz himself had a mixed racial makeup, called Mestizo. Santos said that was part of his mystique as a leader, early on.

“He emerged as a mestizo hero. He came out of very common origins, but became a dictator,” Santos said. “He was responsible for electrification, but he was responsible for creating what we think of today as an oligarchic elite.”

While in the army, Urrutia did field surgery on a wounded soldier, and officer Victoriano Huerta was impressed by his work.

Huerta would eventually overthrow Mexico’s first elected President Francisco Madero, and then offer Urrutia a job as Minister of the Interior. Urrutia took it, but soon figured out that was a mistake. Elise said he didn’t serve long.

“Less than 100 days. He was a part of the regime of Victoriano Huerta, which was a lot worse than Porfirio Diaz,” she said.

Urrutia accepted a job running a Mexico City hospital, but due to the swirling chaos of the Mexican Revolution, within a year decided he’d better bolt.

“By the time May of 1914 came along, the situation with the government was really beginning to crumble,” Elise said. “So he was basically being pursued by two groups of people as he was leaving Mexico. One from the right and one from the left.”

Elise said for safety, he disguised his family.

“He and his wife and six of his 11 children at that time dressed as peasants and traveled in disguise from Mexico City to VeraCruz,” she said.

U.S. Troops were occupying Veracruz, and they seized Urrutia and his family. They allowed them transport to Galveston, Texas and from there they came to San Antonio, where he sent for his remaining children.

Santos said he set up his medical practice and built a 10,000-square foot home called Quinta Urrutia.

“He embraced all of these complex origins of the Mexican story at the Quinta Urrutia. There were classical paintings, but also Indigenous statuary. A statue to the great earth mother goddess, Coatlicue and her daughter Coyolxāuhqui the moon goddess. Those two sculptures, in fact, would ultimately find their way to the Miraflores Garden,” Santos said.

“And they're there today, mashed up. The head of the daughter Coyolxāuhqui is actually put on the kind of monstrous serpent skirted body of Coatlicue where you can see that, you know, it's survived all these decades. And so they're regarded as, you know, very powerful entities unto themselves. And yet here in San Antonio we have this incredible artifact of the head of the daughter placed on the body of the mother.”

And Santos said one of the spookiest aspects is the power these sculptures still have over some.

“One of the most amazing things about one of my recent visits to the Miraflores site — people have left offerings to the goddesses,” he said. “There are little quarters stuck into these niches in the statue as if it's still activated.”

Elise said Urrutia bought the property where he built Miraflores in 1921.

“The piece of land was 15 acres at the time. It went all the way from Broadway to the San Antonio River, from east to west and north to south, from Hildebrand to two blocks south,” she said.

One of the sad parts of Miraflores today is that most of its trees are gone. This was the edge of town in 1921, so these were woods.

“I think it was very much a wilderness area, although he did wind up planting many trees on the 5 acres that now remain as Miraflores,” she said. “There's also a lot of trees along the river, the cypress trees. He planted those.”

In researching her book and studying the landscape, Ms. Urrutia had a revelation.

“What I realized was that the garden really kind of had five sections to it. When you first walked in there were some tile benches and beautiful trees and a wide vehicular entryway with the statue of Porfirio Diaz at the end,” Elise said. “And then as you sort of came to the statue of Porfirio Diaz, you entered the second section, which was this long esplanade that headed right through the center of the garden, headed south.”

Also there past the Diaz sculpture: a three-story tower with a curved interior stairway. Thousands of books were in bookcases lining those three stories.

“You could go up into the tower and see the whole property. From that tower point, you're sort of taken back into ancient Mexico along this Esplanade,” Elise said.

“You have this incredible Dionicio Rodriguez fountain on your left, which is no longer in existence, but it basically resembled an erupting volcano. And then you came to this statue of Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor. Just after that, there was this incredible pool that the Rodriguez fountain emptied into via a stream that went between the two.”

If you then turned west toward the San Antonio River there was a large reflecting pool. Elise said in 1940 Mexican Sculptor Ignacio Asúnsolo was contracted by a patient he’d saved to make a large sculpture of Dr. Urrutia.

“And so around that sculpture he created this plaza that was like an enclosed room with gardens surrounding the plaza, almost like walls,” she said.

The last section is nearest to Hildebrand and called Quinta Maria, because of the small cottage of that name that Doctor Urrutia built there.

“He moved this large Samothrace sculpture there, which is facing in that direction towards [the University of the] Incarnate Word was sort of his connection to his spirituality,” Elise said. “It also has kind of a fairy tale-like feeling. It had a poppy field with flowers and it had Dionicio Rodriguez's pedestrian gate, which is like a big old hollowed out tree.”

Dr. Urrutia created two sanctuaries in San Antonio: Quinta Urrutia, his home, and Miraflores. Santos said to understand Urrutia and the concepts he brought to those two sanctuaries, you have to give them some thought.

“When you really look closely at the details of the architecture of the mansion and the landscape plans and statuary and tiles and inscriptions of Miraflores, you see a very profound and almost a mythically daring act where he is writing himself, Dr. Urrutia, into the great Mexican epoch,” Santos said. “So it wasn't meant to be figurative or symbolic or allegorical. It was literal.

He said Urrutia left no doubt if you examine the two panels on the massive gate into the property at Hildebrand Street.

“The two great panels of tiles at the entrance to the Miraflores Garden that face. Hildebrand — you see that one is about Hernán Cortés and his triumph in 1520 in Mexico City overtaking the Aztec empire. The other one is Dr. Aureliano Urrutia, 1920,” he said.

Dr. Urrutia worked hard to negate his short tenure working for Huerta. Santos says that while his timing for getting educated in Mexico was good, in a sense his arrival in San Antonio wasn’t.

“After the events of 1836 [the Texas Revolution], Mexican-ness, the Spanish colonial legacy, went into something of a twilight. By the end of the 19th century, it is a predominantly Anglo-German city, completely transformed by Mexican migration in the 20th century,” Santos said. “So by the time of the 1970s, this is a Mexican city again. There was this ebb and flow. But he was in that kind of in-between period of being very Mexican in what had become essentially a kind of Anglo-German majority town with a very distinct Anglo majority, Anglo-German elite.”

Urrutia died in 1975, and Miraflores went through several owners, and many changes were made. Many, it seems, without understanding the garden’s historic importance.

A large number of the park’s art pieces simply disappeared, taken by vandals and others. In 2006, the city of San Antonio did a land swap and got ownership of Miraflores, with an eye on preservation and reuse. Brackenridge Conservancy’s Lynn Osborne Bobbitt said they went right to work.

“The city engaged RVK architects to do a master plan in 2007, and they documented the antiquities that were there — benches, urns, walkways. They created a drawing and a plan and made recommendations about what could be restored, what could be repurposed,” Bobbitt said. “The Texas Historical Commission was called back in because every time you dig, you find something else underground that we didn't know was there.”

Historic discoveries necessitated Historical Commission studies, then re-designs approved by the Historic Design Review Commission, delaying the entire process. Now though she said, the central fountain structure and walkways are re-built.

“The ADA accessible walkway is complete and it will go from the bridge that was built in 2009, from the park side into Miraflores. And we're waiting for the irrigation to be put in and then at the proper time to plant the trees and shrubs and other vegetation so that you will be entering like rooms of plantings,” Bobbitt said.

They will wait for cool weather to replant Miraflores. As to what exactly will happen to the park, that’s still to be determined. Many complain that its rejuvenation has been slow. Bobbitt agrees.

“I'm getting older, too,” she laughed. “I'd like to see something done while I can enjoy it, too. But it takes time. And just like Brackenridge Park, this park is so important to everybody in the city that people want to have their say.”

The renovation is dependent on how the city park’s budget gets built, and private donations targeting individual projects are collected. Bobbitt expects the park to be open in the short coming years for the public to enjoy in moderation.

“It would be fun for people who are coming to this city, as well as those of us who live here, to be able to enjoy it and understand it better,” she said. “And through Elise’s book, there are amazing photographs and stories that she has told that can now be shared with the public and interpreted through signage and photographs there in the park.”

Ms. Urrutia thinks Miraflores may be at an inflection point.

“I think part of the problem, since the city has owned it since 2006, is that there has never been really the funding or the will to sort of have an overall approach to the restoration project,” she said. “The Cultural Landscape Report recommends that.”

John Phillip Santos says that our country’s self image and professed history is highly Eurocentric, and Urrutia’s story is in actuality, this country’s lesser told one. And Miraflores is an opportunity to hit the reset button on that.

“It invites people to, in a sense, journey through their imagination into all kinds of questions about San Antonio's unique legacy. And Dr. Urrutia does that for us in a way that connects San Antonio directly to Mexico City, to Xochimilco to this mystery of the mestizo mind and heart,” he said. “It's a critical part of San Antonio's role in the United States to testify to this other American origin story.”

![Recuerdo de Xochimilco [Memories of Xochimilco] a garden at Sanatorio Urrutia, ca. 1911](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/db28eda/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1157x713+0+28/resize/880x542!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fa6%2F15%2F23cf102640ae87147983e8a144a0%2F7-recuerdo-de-xochimilco.jpg)