In a span of less than two weeks, rampant violence has driven nearly 125,000 members of a Muslim ethnic minority from their homeland. And as the Rohingya cross the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh, they have borne little but the clothes on their backs and their brutal stories of the systematic rape, murder and arson they escaped.

"My husband was shot in the village. I escaped with my son and in-laws," a 20-year-old Rohingya named Dilara told the human rights agency at the United Nations, which released its estimates on refugees Tuesday. She had made it to Bangladesh with her toddler after a three-day walk, hiding occasionally to escape the gaze of Myanmar security forces.

"I don't know where I am," she said. "I just knew to run to save my life."

Since a Rohingya militant group launched a short-lived assault on Myanmar military posts on Aug. 25, reports of the military's violent reprisals on Rohingya civilians have streamed out of the country. Observers fear the assault, which was condemned by the U.N., merely exacerbated existing prejudices against Rohingya Muslims in Buddhist-majority Myanmar, where they are viewed as outsiders without citizenship despite long roots in the country.

In the border state of Rakhine, home to roughly 1 million Rohingya, Human Rights Watch says satellite evidence suggests whole Muslim villages have burned to the ground.

"The brutality is unthinkable. They're killing children. They're killing women. They're killing the elderly. They're killing able-bodied men and boys," Matthew Smith of the human rights group Fortify Rights told reporter Michael Sullivan earlier this week. "It's indiscriminate."

At the same time, international groups have protested that the Myanmar government is stymieing efforts to supply aid to the region.

"The Muslims are starving in their homes. Markets are closed and people can't leave their villages, except to flee," one humanitarian official said in an Amnesty International statement Monday. "There is widespread intimidation by the authorities, who are clearly using food and water as a weapon."

Taken together, there are "clear signs that more [refugees] from Myanmar will cross into Bangladesh before [the] situation stabilizes," Mohammed Abdiker, director of operations and emergencies at the International Organization for Migration, tweeted Tuesday.

Of those who are crossing the border, Abdiker says "many are vulnerable" and most are "women, children & the elderly."

The IOM has put out a plea for support, saying the settlements receiving refugees in Bangladesh are already reaching a crisis point.

"The new arrivals are putting immense strain on the existing support structures. These need to be immediately scaled up to ensure lives are not put at risk," Sarat Dash, chief of the IOM's mission in Bangladesh, said in a statement released Tuesday.

The group estimates roughly 400,000 undocumented migrants from Myanmar now live in Bangladesh, about half of whom are living in makeshift settlements in the border city of Cox's Bazar alone.

Myanmar's military, for its part, maintains that Rohingya militants are responsible for the burned villages — and that they are plotting terrorist attacks and bombings later this month. According to The Associated Press, a statement posted on the military commander in chief's Facebook page alleged the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, or ASRA — the same group that launched the assault last month — was planning the violence to grab international attention.

The statement "gave no evidence to back up its claims," the AP notes.

The military has also defended its restrictions on international aid by saying the supplies were finding their way into militant camps, suggesting support for the militants — an allegation Amnesty International vehemently denied.

"The accusation that international humanitarian organizations are supporting armed actors in Rakhine State is both reckless and irresponsible," the group's director for crisis response, Tirana Hassan, said Tuesday. "The Myanmar authorities must immediately stop spreading misinformation and circulating unfounded and inflammatory accusations."

Beyond Myanmar's borders, ire is coalescing around the country's de facto civilian leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. A Nobel Peace Prize laureate for her decades-long struggle for democracy in Myanmar, Suu Kyi has nevertheless remained conspicuously silent as the bloodshed has unfolded.

As NPR's James Doubek noted, Suu Kyi's fellow Peace Prize laureate, Malala Yousafzai, called out the leader over Twitter this week, saying "the world is waiting and the Rohingya Muslims are waiting" for her to repudiate the violence.

Suu Kyi's defenders argue the matter isn't quite so simple, since the military remains in control of the country's important mechanisms of power. Poppy McPherson, a journalist currently in Myanmar, explained on All Things Considered:

"Some people say she's playing a long game. She's trying not to do anything that would anger the military. There's also the argument that, as we've seen by the reaction to this here in Myanmar, many people view the Rohingya as a security threat. They view them as illegal immigrants. So for Aung San Suu Kyi to come out in support of them could make her deeply unpopular domestically."

That argument is no longer good enough for the U.N. special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, Yanghee Lee. Suu Kyi may be "caught between a rock and a hard spot," Lee said recently, according to The Guardian, but "I think it is time for her to come out of that spot now."

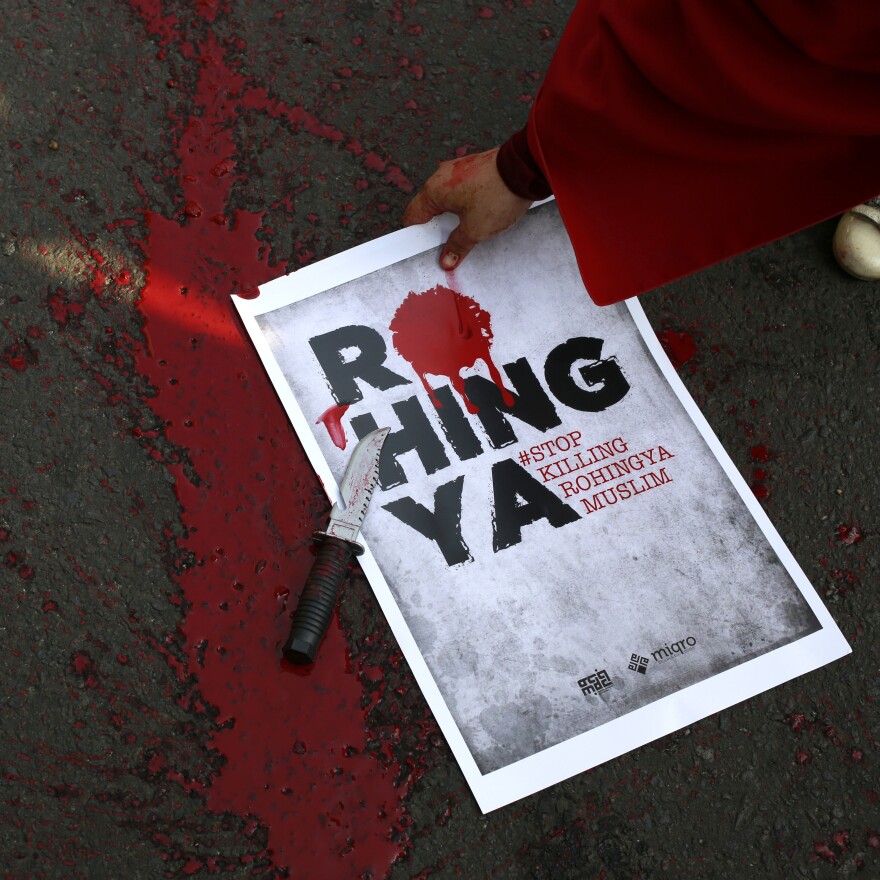

That sentiment has been echoed by several Muslim-majority regions around the world, which have been watching the situation with particular interest. CNN reports that in Indonesia and Malaysia, Pakistan and Chechnya, demonstrators have taken to the streets in recent days to protest the Rohingya's treatment.

Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov said "hundreds of thousands" of protesters gathered in the capital, Grozny, to "demand the guilty to be prosecuted and an international investigation launched" into the "genocide that's going on in Myanmar."

U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres told reporters "we are facing a risk" of ethnic cleansing in Myanmar, according to The Guardian. "I hope we don't get there."

To that end, he said in a statement he has written to the Security Council about the situation — and that includes what he called "the root causes of the crisis."

"It will be crucial to give the Muslims of Rakhine state either nationality or, at least for now, a legal status that will allow them to have a normal life, including freedom of movement and access to labour markets, education and health services."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.