Earlier this month, a woman selling hard-boiled eggs at a bus station in Nairobi got into an argument with a customer over 70 cents she said he owed her.

The man mocked the mother of two — who was wearing a short skirt — for being "indecently dressed," then rallied dozens of nearby men to strip her naked while others filmed the mob attack with their cellphones.

The graphic video, instead of prompting arrests, was met with some approval on Kenyan social media. The miniskirt has been decried as a "foreign" blight on traditional African dress and values. Earlier this year, miniskirts were declared illegal by parliamentary decree in neighboring Uganda.

In Nairobi, just around the corner from where that bus station attack took place, in a narrow stall stocked with brightly colored fabrics, Marianne Njambi does a brisk trade in women's clothes. Miniskirts, she says, are one of her best-selling items.

"This is our country," she laughs. "Women have to wear what they want."

Then Njambi slowly reaches into her purse and pulls out her cellphone to show me the latest stripping video she'd downloaded just that morning. Since that first attack on the egg-vendor there has been a new victim, and a new video, almost every day.

We watch the video together with some other women in the shop. This one takes place inside a bus. A woman's canary yellow dress is pulled up to her waist. The cellphone camera zooms in as her legs are forcibly spread open by some of the male passengers.

"Oh God, please help me, please stop," she begs in Swahili, as the men are heard laughing.

When the one-minute video ends, Njambi puts her phone back in her purse and shakes her head.

"It is getting worse," she says. "Every day. It's routine now. If someone wears something short, not even short, a bit short."

She glances outside at the bus station on the corner, crowded with commuters but also pickpockets and unemployed drifters.

"Since they have started stripping girls, I started fearing," she says.

These widely shared videos have found their way into the homes of suburban moms and middle-class Kenyans who wouldn't normally venture to these rough parts of town.

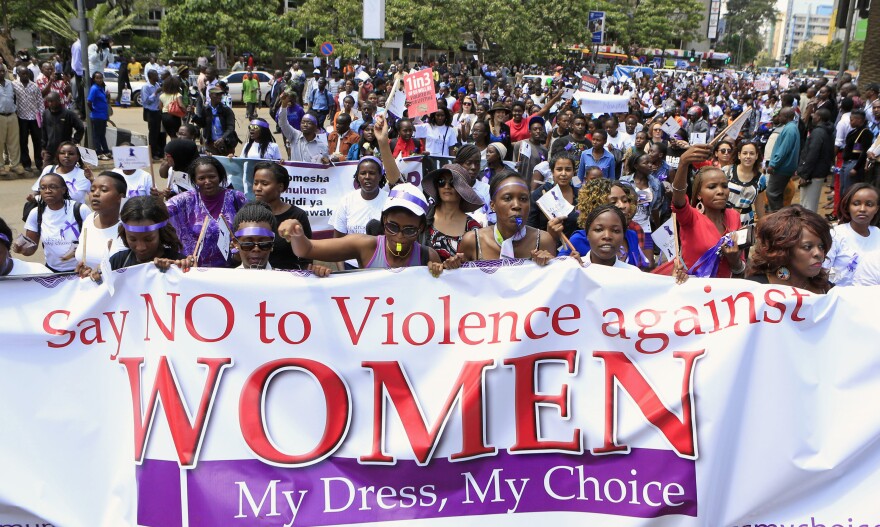

A popular Kenyan mom's Facebook group set up to exchange information about childcare and parenting has taken on an activist role, organizing a rally in downtown Nairobi last week where hundreds of demonstrators chanted "My dress, my choice!" (the name of a Twitter campaign as well) and demanded government action.

Kavinya Makau, who works at the Nairobi office of the human rights group Equality Now, says the stripping videos have provided an "opportunity" for social change, generating more popular outrage and soul searching in this predominantly Christian country than far more brutal crimes of sexual violence or rape.

"Kenya is now having a conversation around violence against women for the first time in a very long time," Makau says.

However, the same viral videos that are galvanizing activism are also inciting copycat attacks of increasing violence, she says. In a subsequent video, a woman was beaten. Another was raped with a beer bottle.

Each new assault, Makau says, sends a message to would-be perpetrators that men can attack women in broad daylight with impunity.

Kenyan police say they can't arrest people if victims don't come forward; women's rights activists estimate that only 1 out of 5 victims of sexual violence in Kenya ever report the crime.

As a result, Kenya's national bar association, the Law Society of Kenya, is requesting special permission to prosecute the crimes.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))