Dec. 30 is the deadline to submit a comment to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services over a proposed fee hike to access some records, some of which date back more than 100 years and are useful to genealogists.

The USCIS wants to increase the fee for obtaining immigration files by 500%, which means some people would have to pay more than $600 for the documents. The move would affect families of the millions of people who immigrated to the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

"This is immigration history," Renée Carl, a genealogist in Washington, D.C., who works with clients who use the records, tells NPR's David Greene.

"If someone is coming from a displaced persons camp in Europe, they would have filled out all this paperwork while still in Europe," Carl says. "Then you get the information on when they come in. You get a photograph if there's a visa file. You almost always get a photograph."

There are millions of records held at the agency, Carl says. These include alien registration files, files for certificates of naturalization and visa files, if one applied for a visa to come to the United States. "There might be something called a registry file if, during the process of naturalization, the government couldn't find you on a ship manifest, so they were trying to document how you entered the country in the first place," Carl says.

For people trying to trace their family histories, these files can offer critical information, including photos. She says genealogical research goes beyond just wanting to know relatives' names; people want to understand the kind of lives their ancestors lived.

"Sometimes you've never seen a picture of your great-grandfather or your grandfather other than as a grandfather, not as a young person," Carl says. "This gives you a way to understand what their lives were like when you can't ask them the questions anymore."

Even when the files don't contain photos, they almost always include a signature, Carl says, "which is a way to have that human touch in a record."

USCIS documents can be especially important for populations in the U.S. affected by discriminatory immigration laws, Carl says. These groups include Japanese-born residents who were denied citizenship until after World War II and people of Chinese descent who were subject to immigration and citizenship restrictions between the 1870s and the 1950s.

Carl and colleagues have created a website with more information on the files USCIS has, the proposed fees, as well as how to comment.

She says she first learned about the value of immigration documents when doing research on her own family.

"My grandfather came to this country as a child and became a citizen," she says. "But in the 1960s, my grandfather had no idea where his certificate of naturalization was. He wanted a copy of it that had his name on it. And he also needed to prove how old he was to Social Security so he could start collecting his benefits."

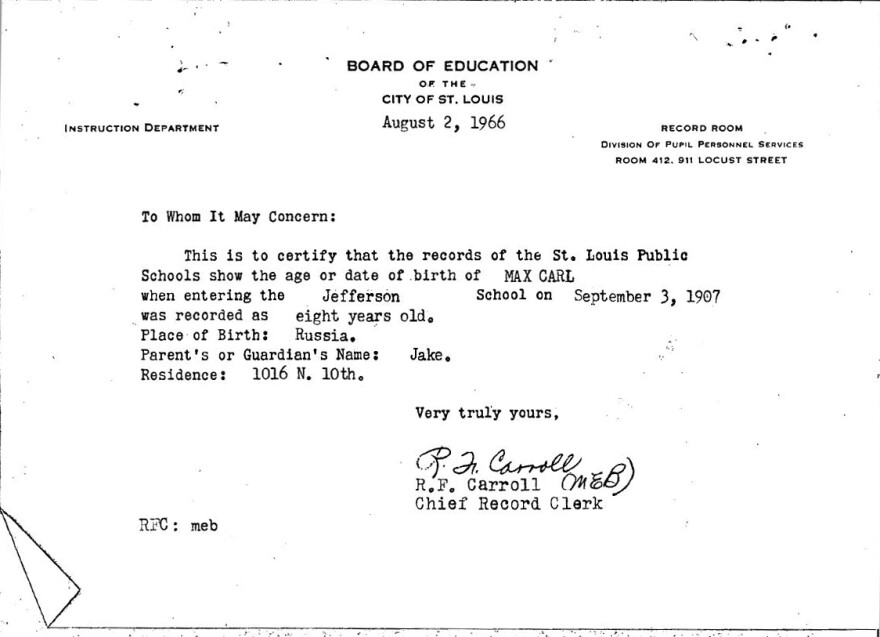

He'd come from Eastern Europe as a child and Carl's grandfather did not have a birth certificate, so in order to prove his age, Carl found letters in his file from the St. Louis school board saying that he started first grade at age 8.

"It gave the name of the school that he attended. These are little things, but it gave me this insight into a person as a child," she says. "You realize they had this whole life that they lived. So these records are one way to take a peek back into a different part of our immigrant ancestors' lives."

If the fee increases go through, Carl says, it would cost a minimum of $240 to simply put in a search request for records from USCIS. The fee would cover some records, she says, "But if there is a paper file, they would add on another $385 to the fee. So that's a total of $625 for one file on one person."

Currently, it costs about $65 for a search and another $65 to receive the records.

"There's a huge difference," says Carl. "It's already expensive for records that should be at the National Archives. Many of these records should be at National Archives and free for people to access."

A USCIS press release says the fees are needed to cover the costs of processing these applications. But Carl says the fees are redundant.

"Our immigrant ancestors paid and filed fees when they filled out the forms in the first place. If these records were transferred over to the National Archives, they would be available for research, and these records would then be held in a place that's used to handling records all the time, not in an agency that focuses on immigration and naturalization, she says.

NPR's Gisele Grayson and Jon Hamilton produced this story for the Web.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))