Maria Hinojosa is a trailblazing journalist.

She was the first Latina journalist at NPR and one of the first Latinas at CNN.

Hinojosa is also the anchor and executive producer at Latino USA and founder and CEO of The Futuro Media Group.

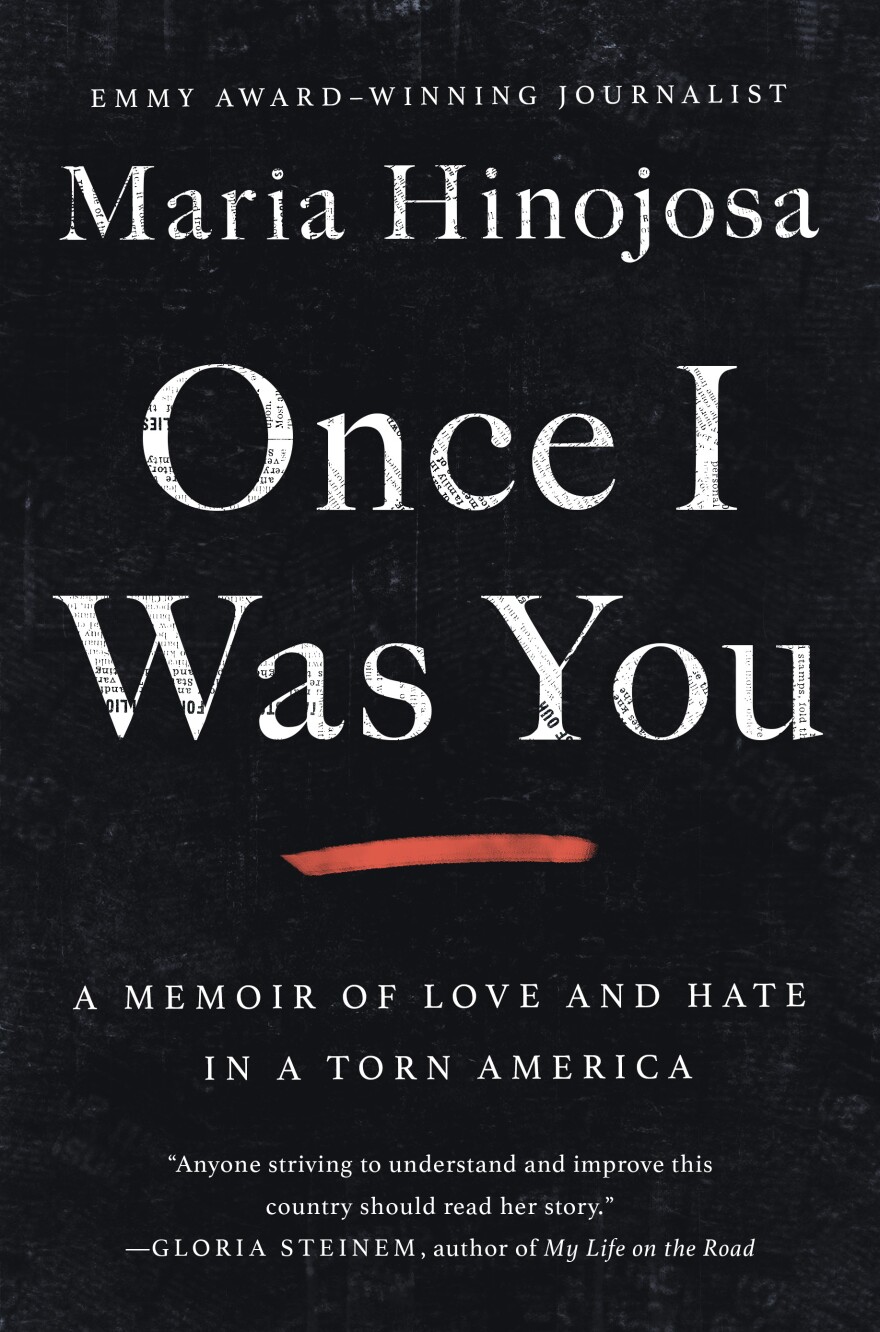

Now, Hinojosa is also the author of “Once I Was You: A Memoir of Love and Hate in a Torn America.”

TPR’s Reynaldo Leaños Jr. spoke with Hinojosa about her book, the current political landscape and her nearly 30-year career as an award-winning journalist.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Reynaldo Leaños Jr: Hi, Maria. Thanks a lot for making time today. I really appreciate it.

Maria Hinojosa: Rey, you are one of my favorite people in the state of Texas. So, of course, I'm going to make time for you.

RL: Maria, in your book, you start off with the scene at the McAllen International Airport, and you say this: “I was bearing witness to and the gentlest of ways, a quiet, intimate conversation to one of the greatest modern horrors of the USA.” Can you talk a little bit about that moment? And you know, why you decided to start off your book like that?

MH: My dear friend Sandra Cisneros, who used to live in San Antonio and is my muse and my one of my best friends. She said to me at one point, “Don't write about the things that you remember, write about the things that you've forgotten, that you wish you could forget that are so buried.” And so when I thought about something that I had witnessed that I had wished I could forget, it was the scene and it happened in the McAllen airport. It was early one morning, and I was, I mean, I was in an airport. I used to live in airports before the pandemic, so I know airport culture, I know the vibe.

And suddenly I just saw this little girl. I think that's what happened is that I just was drawn to her beauty. She had long hair. She's like maybe 10 years old, 12 years old. Thin, tiny. Beautiful eyes. But I realized she wasn't actually looking at me. She was looking right through me. And that was the hint because most kids in airports are like happy jumping this and that. She was like a stone. And that's what I was like, “Wait, what's going on here?” And then I did kind of a wide-angle pull back, and I was like, “Oh my God, here's what's happening. You're witnessing this group of children being transported right now on this flight on United Airlines from McAllen to Houston. Oh, my God. These are the kids. These are the children. They're right in front of me. I believe these children are being trafficked.” The definition of a person being trafficked is you don't know who you are, who's taking you anywhere. You don't know where you're going. You don't have your ID. And you've been told not to speak to anyone. This is the situation for these children. So they, in my view, are being trafficked by these — quote unquote — chaperons from southwest key. And I tried to speak to them and I'm not allowed, you know I have an encounter with this little girl before they realize what's happening. And so, yeah, I confirm with her she was being held in that converted Walmart that was now filled with children in cages. And we had a beautiful little moment. I realized, like maybe I can, maybe I can offer her a little bit of affection just with my eyes or with my tone. And that's why she softened. And then I was told I was not allowed to speak to those kids, by the way, the people who were telling me this were other Latinos who are actively playing a role in what's happening with this entire immigration detention, deportation industrial complex.

This is not just about a job. So in the end, I start speaking to this little girl, and the group of kids went from probably a 15-year-old down to a five-year-old. And I just started saying in Spanish, “They should know that they can speak to a journalist that's not against the law. And we need to let them know that people here care about them. We want to know that they're OK. They are not the enemy.” And then I wrote, you know, I wanted this little girl to hear me saying these things because I wanted her to know that I saw her. “I see you because once I was you,” which led to this kind of thing that happened in my life, which that under very different circumstances and me with a lot of privilege and a green card. But I could have been one of those children who was taken. And I didn't really quite understand that until the writing of this book.

RL: Throughout your entire book, you're extremely vulnerable. You know, you talk about your personal life and career, but there's also a lot of history. But I was wondering, what's one of your favorite pieces of history that you have in your book that you really hope people take away?

MH: Somebody asked me what was the most difficult part of writing the book. Yes, I cried when I had to write about my sexual assault. My rape. Yes, I cried when I was writing that. But the more difficult part was actually writing the history. And the reason why I understood I was like, why it was so hard because I didn't feel I had a right, you know, I wasn't born in this country. I'm not a historian academically. And so I was like, I can't do this. And it's like, no, actually, I can. And I want people to understand because there's a lot of people who right now are saying we have to retell our version of history and this is over at. OK. But the facts are that there were multiple indigenous people living on this land before anybody arrived. So it was already multicultural, by the way. Multiple languages are spoken. The fact is that the first contact from Europe to here is when they arrive. The Spaniards arrived to St. Augustine in Florida. So Spanish is the second language that is spoken here after indigenous languages. The next settlement is in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Then the pilgrims arrive at Plymouth Rock. What's that about? What would happen, Rey, if we actually knew if young Latinos and Latinos actually know, you know, know the first language that was spoken here after indigenous languages was Spanish? Yo, would we feel prouder? I bet we would.

So I'm not saying that's to be like, “This is my version.” This is actually history. It is the truth. And the truth is, this country also gives us mixed messages. Where I am right now, I'm in Harlem, New York. You know, if I was a really good baseball player, I could maybe throw a baseball all the way down to the Statue of Liberty a few miles down. You know, the Statue of Liberty says that she's welcoming, but the policies say everything, but that the last person who increased substantially, the number of refugees allowed in this country was someone from Texas vs Connecticut, George H.W. Bush. That was the last person he was the last progressive on the issue of refugees. Yes, that's the truth. So the Democrats and the Republicans, both of them have thrown immigrants under the bus consistently and supported immigration policies that are harmful to people whose only true crime. Is that we were not born in this country. That's the only difference between me.

RL: Thank you so much for being here, Maria. I really appreciate it.

Listen above for the full interview.