In December 1963, a military family named the Gardners had just moved to San Diego, Calif.

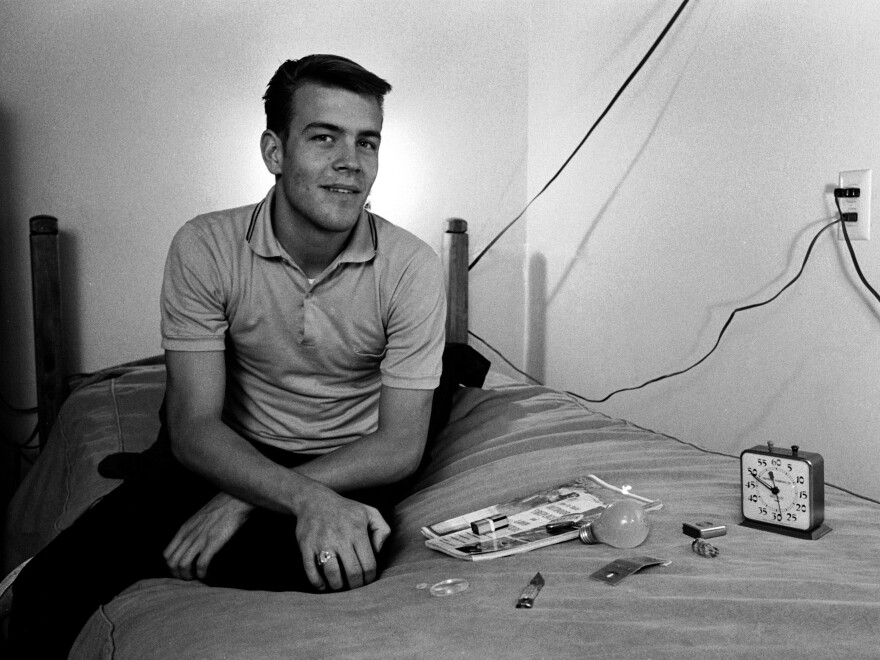

The oldest son, 17-year-old Randy Gardner, was a self-proclaimed "science nerd." His family had moved every two years, and in every town they lived in, Gardner made sure to enter the science fair.

He was determined to make a splash in the 10th Annual Greater San Diego Science Fair.

When researching potential topics, Gardner heard about a radio deejay in Honolulu, Hawaii, who avoided sleep for 260 hours.

So Gardner and his two friends, Bruce McAllister and Joe Marciano, set out to beat this record.

Randy Gardner spoke to NPR's Hidden Brain host Shankar Vedantam in 2017.

When asked about his interest in breaking a sleep deprivation record, Gardner said, "I'm a very determined person, and when I get things under my craw, I can't let it go until there's some kind of a solution."

Of his scientific trio, Randy lost the coin toss: He would be the test subject who would deprive himself of sleep. His two friends would take turns monitoring his mental and physical reaction times as well as making sure Gardner didn't fall asleep.

The experiment began during their school's winter break on Dec. 28, 1963.

Three days into sleeplessness, Gardner said, he experienced nausea and had trouble remembering things.

Speaking to NPR in 2017, Gardner said:

"I was really nauseous. And this went on for just about the entire rest of the experiment. And it just kept going downhill. I mean, it was crazy where you couldn't remember things. It was almost like an early Alzheimer's thing brought on by lack of sleep."

But Gardner stayed awake.

The experiment gained the attention of local reporters, which, in Gardner's opinion, was good for the experiment "because that kept me awake," he said. "You know, you're dealing with these people and their cameras and their questions."

The news made its way to Stanford, Calif., where a young Stanford sleep researcher named William C. Dement was so intrigued that he drove to San Diego to meet Gardner.

Along with a U.S. Navy medic named Lt. Cmdr. John J. Ross, Dement helped monitor Gardner's health throughout the experiment. Dement also helped Gardner stay awake by playing basketball or games of pinball with Gardner.

When asked about his win percentage in pinball, Gardner said, "I did good. I think I beat him most of the time."

Gardner actually won all the time.

"Physically, I didn't have any problems," Gardner said. "But the mental part is what went downhill. The longer I stayed awake, the more irritable I got."

On Jan. 8, 1964, Gardner reached the last day of the experiment. He had been awake for 11 days straight — 264 hours — a new Guinness World Record.

Gardner said, "I had a very short fuse on day 11. I remember snapping at reporters. They were asking me these questions over and over and over. And I was just — I was a brat."

After talking with reporters, Gardner was sent to a nearby naval hospital. There, doctors observed his brain waves through an electroencephalogram machine he was hooked up to. Medically, Gardner was perfectly healthy.

So, at the naval hospital, Gardner slept for 14 hours. After he woke up, he said, he felt "groggy, but not any groggier than a normal person."

Gardner, McAllister and Marciano won first place at the San Diego science fair.

Although Gardner's record was broken within the same year, his experiment is one of the most well-documented cases of sleep deprivation. It supported later studies of "microsleeps." According to Guinness World Records, microsleeps are "momentary lapses into sleep that last for just a few seconds."

Decades later, the field of sleep research had grown exponentially, including the detrimental effects of sleep deprivation.

The last Guinness world record for sleep deprivation was awarded in 1986 to Robert McDonald, who deprived himself of sleep for almost 19 days. In 1996, the GWR stopped tracking sleep deprivation, citing the "harmful" effects of sleeplessness.

In making this decision, Craig Glenday, editor-in-chief of Guinness World Records, wrote:

"Sleep is just one of those key, absolute, fundamental parts of human nature — we need our sleep. And I think that's why this is a particularly fascinating record, because challenging the extremes of something that is so absolute is key to understanding who we are as a species."

When Gardner spoke to NPR in 2017, he mentioned that he developed insomnia as an adult. He said, "About 10 years ago, I stopped sleeping. I could not sleep. I would lay in bed for five, six hours, sleep maybe 15 minutes and wake up again. I was a – I was a basket case."

It's unclear what triggered his condition. But Randy Gardner says he sees it as some kind of "karmic payback" for his science experiment 60 years ago.

More moments in history

Copyright 2024 NPR