Military names can echo down through the ages, a fact underlined by the current fight in Washington, D.C., between President Trump and Congress, which has voted to strip the names of Confederate generals from several Southern Army bases.

The president has vowed that won't happen, but the battle might not be resolved before Election Day.

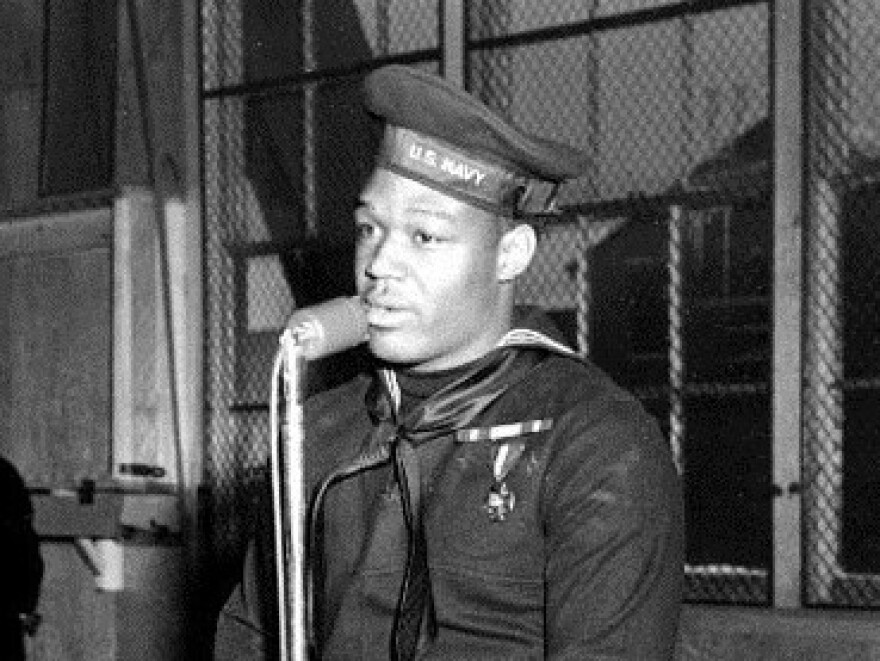

The Navy, meanwhile, has quietly charted a new course. A supercarrier now on the drawing boards will be christened the USS Doris Miller.

It's the first supercarrier to be named for an enlisted sailor and the first to be named after an African American.

Most supercarriers are named for U.S. presidents — the USS John F. Kennedy. USS Ronald Reagan. USS Abraham Lincoln. Henry Kissinger called them "100,000 tons of diplomacy," and that power has long been reflected in the Navy's conventions for naming them.

Doris Miller, who went by "Dorie" in the Navy, was one of the first American heroes of World War II.

During the attack on Pearl Harbor, as his battleship, the USS West Virginia, was sinking, the powerfully built Miller, who was the ship's boxing champion, helped move his dying captain to better cover, then jumped behind a machine gun and shot at Japanese planes until his ammunition was gone.

As a Black sailor in 1941, he wasn't supposed to fire a gun even. This means that when he reached for that weapon, he was taking on two enemies: the Japanese flyers and the pervasive discrimination in his own country.

"One of the ways in which the Navy discriminated against African Americans was that they limited them to certain types of jobs, or what we call 'ratings' in the Navy," said Regina Akers, a historian with the Naval History and Heritage Command. "So, for African Americans, many were messmen or stewards. Dorie Miller was a messman, which meant that he basically took care of an officer, laid out his clothes, shined his shoes and served meals."

''He should be recognized and honored"

Akers said much of the attention at the time, and since, has been on Miller firing the anti-aircraft gun, which he wasn't even trained to do. In fact, it's a moment Hollywood briefly portrayed in several movies about the attack.

But Akers said what Miller did afterward is just as important: He began pulling injured sailors out of the burning, oil-covered water of the harbor, and was one of the last men to leave his ship as it sank, and continued getting sailors to safety afterward.

An official Navy commendation list of those whose actions during the attack stood out mentioned a Black sailor.

But it didn't bother to name Miller, a 22-year-old sharecropper's son from Waco, Texas.

"It made two lines in the newspapers," said Frank Bolden, who was a war correspondent for The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the leading Black newspapers of the day. He spoke in an interview with the Freedom Forum before his death in 2003.

"The Courier thought he should be recognized and honored. We sent not a reporter, we sent our executive editor to the naval department. They said we don't know the name of the messman. There are so many of them."

A pivotal moment

The paper though wasn't about to give up, Bolden said. The Black press knew that by getting this unnamed sailor proper recognition, it could undermine a stereotype that African Americans weren't any good in combat.

"The publisher of the paper said, 'Keep after it,' " Bolden said. "We spent $7,000 working to find out who Dorie Miller was. And we made Dorie Miller a hero."

This was a pivotal moment, said Akers, the Navy historian.

"And so the African American community just swells up with pride," she said. "But at the same time, they're mad at the Navy for not having formally shared what Dorie Miller did."

Black leaders at the time were already pressuring President Franklin D. Roosevelt for more opportunities for African Americans in the booming war industry and in the military. Roosevelt barely averted a march on Washington at one point.

Miller was awarded a letter of commendation, but the Black press campaigned for a medal. And Adm. Chester Nimitz, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, wanted to take the bold step of upgrading that commendation to the Navy Cross, then the third-highest honor for heroism.

Nimitz understood the value of a diverse force made up of sailors who felt they were being treated fairly. "So in Nimitz's mind the award would be good for the Navy and contradict the institutional racism that the Navy was known for," Akers said.

Roosevelt, eager to keep the nation united behind the war effort, agreed.

Suddenly, Miller was in the spotlight.

"Miller I mean, in just like the flip of a switch, becomes a celebrity," Akers said. "He becomes one of the first heroes, period, of the war, but certainly one of the first African American heroes of the war. He was on recruitment posters. His image was everywhere."

Miller had a low-key personality, and while he backed the idea of expanded opportunity in the Navy, he was hardly a radical. But because of what he had done at Pearl Harbor, suddenly the Black newspapers such as the Courier had a powerful weapon they had been looking for, said Baylor University history professor Michael Parrish, co-author of Doris Miller, Pearl Harbor and The Birth of the Civil Rights Movement.

"He was a catalyst that gave them a lot of strength very early in the war. And they were determined to promote him publicly," Parrish said.

Parrish said that in war after war, African Americans had fought for their country, hoping their service would be rewarded with more rights, only to have their hopes dashed.

Until Miller stepped behind that gun.

"Things came together at Pearl Harbor for Doris Miller and for the civil rights movement, probably to maximum effect," Parrish said. "So World War II was really the turning point in that long struggle."

Even before Miller formally received the medal, the effects of what he had done, trumpeted by the Black newspapers, began to have an effect. The Navy started training Black sailors for jobs such as gunner's mate, radioman and radar operator. Later it began commissioning Black officers.

After the war, in 1948, President Harry S. Truman ordered the military desegregated, a major milestone for the nation. All of that, Parrish said, can be traced to Miller.

This wasn't lost on Black America, even as the changes Miller helped spur were just gaining momentum.

There were songs, and even poets were inspired. In 1943 Langston Hughes wrote:

"When Dorie Miller took gun in hand

Jim Crow started his last stand ..."

Another renowned Black poet, Gwendolyn Brooks, was at once oblique and ferocious in "Negro Hero /To Suggest Dorie Miller."

"In a Southern city, a white man said, Indeed I'd rather be dead.

Indeed, I'd rather be shot in the head

Or ridden to waste on the back of a flood

Than saved by the drop of a black man's blood.

Naturally, the important thing is I helped to save them.

Them and a part of their Democracy

Even if I had to kick their law into their teeth

In order to do that for them ..."

Baylor professor Parrish has a personal connection to the story. His father was a sailor aboard another ship at Pearl Harbor, just a few hundred yards from Miller during the attack. Parrish said he got a startling lesson when he asked what his father knew about Miller's exploits.

"He looked at me and he shook his head and said, 'I never heard of him at the time,' " Parrish said. "White and Black military personnel lived in two separate worlds. That's because white people and Black people, along with other people of color on the homefront, lived in two separate worlds."

"It was probably long overdue"

The decision to name the new supercarrier for Miller was made by Thomas Modly, who was acting secretary of the Navy until April.

"I think it was probably long overdue," Modly said. He said he asked a small group of retired Black admirals he had met to recommend a name. He asked them to try to find an African American enlisted sailor, if possible.

"And someone from World War II, because that was a point at which the country was really united," he said. "And African Americans who served were still in a lot of places growing up under Jim Crow. And so it required a lot of bravery and patriotism."

The retired admirals consulted with an historian, Modly said, "and literally, they came back to me within five days and said it has to be Doris Miller. And the story of Doris Miller is an incredible one, so they didn't need to convince me."

It simply seemed like the right thing to do given the U.S. Navy's diversity, he said, especially compared with the navies of other nations.

"The Navy is made up of every single element of our population; it's probably the most diverse representation of the country. We have about 340,000 active-duty sailors, and they come from every part of the country, every skin color, every ethnicity."

Miller didn't live to see the lasting effects of his heroics.

He went back to sea in the Pacific, and in 1943, his ship was torpedoed and sank. Miller was among the hundreds of sailors who died.

His body was never found. His name, though, still graces schools, roads and community centers around the country.

And the Navy, which at first wouldn't even share that name, will soon give it equal footing with the names of presidents.

Akers, the Navy historian, said Miller was a good role model for sailors, a history lesson in trying to do the right thing.

"Despite the fact that he was denied certain basic constitutional rights because of the racism in our society at the time, Dorie didn't let that deter him," she said. "It didn't lessen his patriotism, his love for country, his determination to serve and to give the Navy his very best, and that says a lot. That says a lot."

Copyright 2020 North Carolina Public Radio – WUNC. To see more, visit . 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))