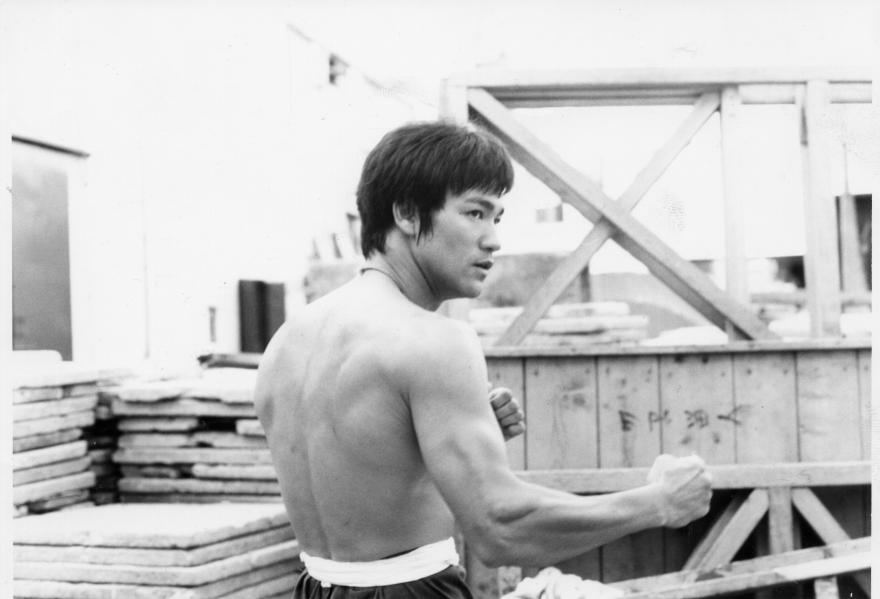

In 1973, Bruce Lee seemed to find stardom overnight following the premiere of the martial arts film “Enter the Dragon.”

But fame came too late for Lee, who died before the film’s opening at age 32. During his short career, Lee broke the long-held stereotypes of Asian men even when those stereotypes threatened to hold him back, as director Bao Nguyen shows in the new ESPN documentary “Be Water.”

Premiering on Sunday, the documentary goes beyond Lee’s legacy as an icon and looks at who he was as a person, Nguyen says.

“I found that in order for us to really aspire and connect to these heroic figures that we relate to, we have to know who they were as a person,” he says. “We had to kind of dive deep into their humanistic qualities.”

The film tells the story of Lee’s early years as a child star in Hong Kong during the 1940s and 1950s. Starting from Lee’s childhood helped Nguyen understand where Lee came from as a person who grew up in a multicultural city like Hong Kong but then moved to the U.S.

The early relationships Lee formed “were formative to who he became as not just a martial artist, but as a philosopher and a film star,” Nguyen says.

Lee first moved to San Francisco, then Seattle when his father sent him to school there in 1959. The film explores how the move shocked Lee.

“When Bruce moves to the U.S., his identity is suddenly a minority, a Chinese minority in a white country. He has to face the conundrum that all immigrants face,” cultural critic Jeff Chang says in the film. “Who am I going to be? What is my identity? How do I express myself? And how in U.S. society can I even be seen?”

For Lee, being seen was complicated by the way that Asian men were portrayed in film and television at the time. Conflicts such as the Vietnam War, the Korean War and World War II influenced many Americans’ views of Asian people, Nguyen says.

“The face of the Asian American or Asian male was very much the face of the enemy to a lot of Americans,” he says. “And so those type of foreign policy decisions and conflicts created these stereotypes and portrayals of Asians on screen as villains, as enemies.”

When Lee eventually went to Hollywood, he broke out of the typical villain roles or sidekick roles based on the model minority myth because he didn’t want to perpetuate these stereotypes of Asian American men, Nguyen says.

At first, Lee taught martial arts in Hollywood because people couldn’t see past his Chinese features and accent. But Lee sounded great for someone who just immigrated to the U.S., Nguyen says, and now people try to replicate his famous accent.

While making the film, Nguyen learned that Lee was “a student of everyone that he taught and everyone that he interacted with,” including his first student, Jesse Glover. As a young black man, Glover wanted to learn self-defense through martial arts because he was a victim of police brutality.

“I think that idea really informed Bruce. He created his ideas of bridging the gap, of building bridges between people instead of building walls and barriers,” he says. “And that’s another thing that I really take away that really is relevant and hopefully resonates with today’s audiences.”

Lee’s frustration with Hollywood sent him back to Hong Kong. When he became a successful film star in Hong Kong, Hollywood became interested in him again.

His last film, “Enter the Dragon,” combined all of the things Lee wanted to do at the time: incorporate his own philosophy and ideas, direct the action and help shape the script, Nguyen says.

Lee died on July 20, 1973, weeks before the film’s release. Sometimes people forget Lee struggled and fought for his position in Hollywood, Nguyen says.

“He didn’t expect that that would be his last film,” he says. “It’s such a tragedy that he had this goal to break into Hollywood, to become a big star, to be this advocate for Asian American representation. And he passed away a few weeks before the opening of the film, so he never realized that dream.”

The documentary uses remarkable photos and film of Lee, and the voices of various people who knew him — but the audience doesn’t see the people who are talking until the end. Nguyen says he wanted to feel Lee in the present moment.

By not showing the modern-day interviews, the audience lives in the same time period as Lee and can place themselves in that world, Nguyen says.

The audience sees Lee in his 20s and 30s, but once the film starts showing the faces of the people who knew Lee, they’re all in their 70s and 80s. When Nguyen sees their faces, he wonders what Lee would have looked like in his 80s.

The title of the film, “Be Water,” references a famous quote from Lee: “Empty your mind. Be formless, shapeless — like water. You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

Lee saw water as a metaphor for the story of the United States, Nguyen says.

The film steps back from Lee’s story and looks at what Asian Americans went through that led up to his rejection by Hollywood. Nguyen thinks of these moments as “rocks” Lee had to move past like water.

The son of refugees from Vietnam, Nguyen says his mother feels more American than Vietnamese now. “The idea of America is fluid,” he says, and obstacles exist in many forms — a lesson from Lee that’s still relevant today.

“We’re always trying to find these moments of progress,” he says. “Right now, we are in a moment where we as a country are crashing against these rocks, and we have to try to find a way to move around it.”

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Allison Hagan adapted it for the web.

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))