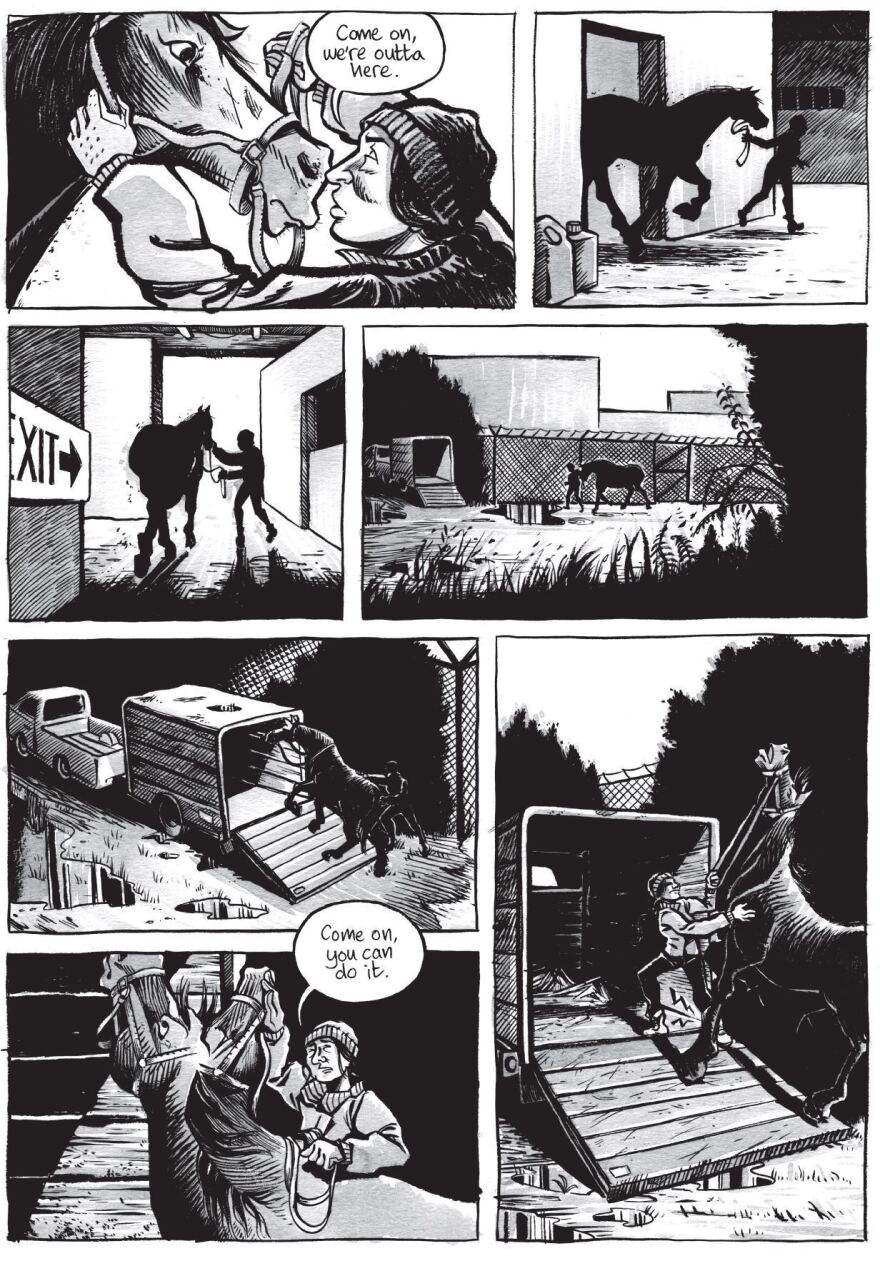

The Hollywood Park stables were quiet that night. Gail Ruffu had planned it that way.

It was around midnight on Christmas Eve 2004, days before the winter racing season would start at Santa Anita Park, about 30 miles away in the Los Angeles suburb of Arcadia.

It would be easy for Ruffu, a horse trainer, to slip into the Hollywood Park stables without anyone noticing.

It would be easy to find the horse she once trained, Urgent Envoy. He was in a barn just across the road from her own. She could lead him into a trailer, talk her way past a guard and drive away. And that's exactly what she did.

"I figured, whatever it takes, even if I go to jail, I have to save this horse's life," Ruffu said.

Ruffu had trained a handful of horses before, but Urgent Envoy was special. Over the previous year, she had helped transform him from a dangerous rebel into a gentle athlete. It seemed he was her one shot to train a winner.

For 15 years, I knew a similar version of this night at Hollywood Park. I had been told that my father, Steve Haney, had hired Ruffu to train his first racehorse. When he fired her, she stole the horse. My dad was the victim.

But then last year, an unexpected discovery changed everything. I stumbled on a graphic novel called Grand Theft Horse. Written by Ruffu's cousin Greg Neri, it paints a much darker narrative. In this version, as in real life, my father is an attorney. But here he is portrayed as a fiend, while Ruffu is the heroine who must save Urgent Envoy from certain death.

The villain in the novel is Bud Clayton, a blond, angular lawyer with a mobster's name. He's a picture of greed, and a foil for Ruffu's best intentions. He is bent on racing his horse with an injured leg.

"I don't care if all four of his legs break off," Clayton says in one scene. "Run him now or I will take him away from you."

The picture was far from flattering, but as Neri told me, it was based on an extensive review of documents and hours of interviews with Ruffu and others who knew her best. But none with my father.

I wasn't sure what to think. It was hard to believe my dad could have resembled this villain, Bud Clayton. I had to know the truth.

Racing deaths

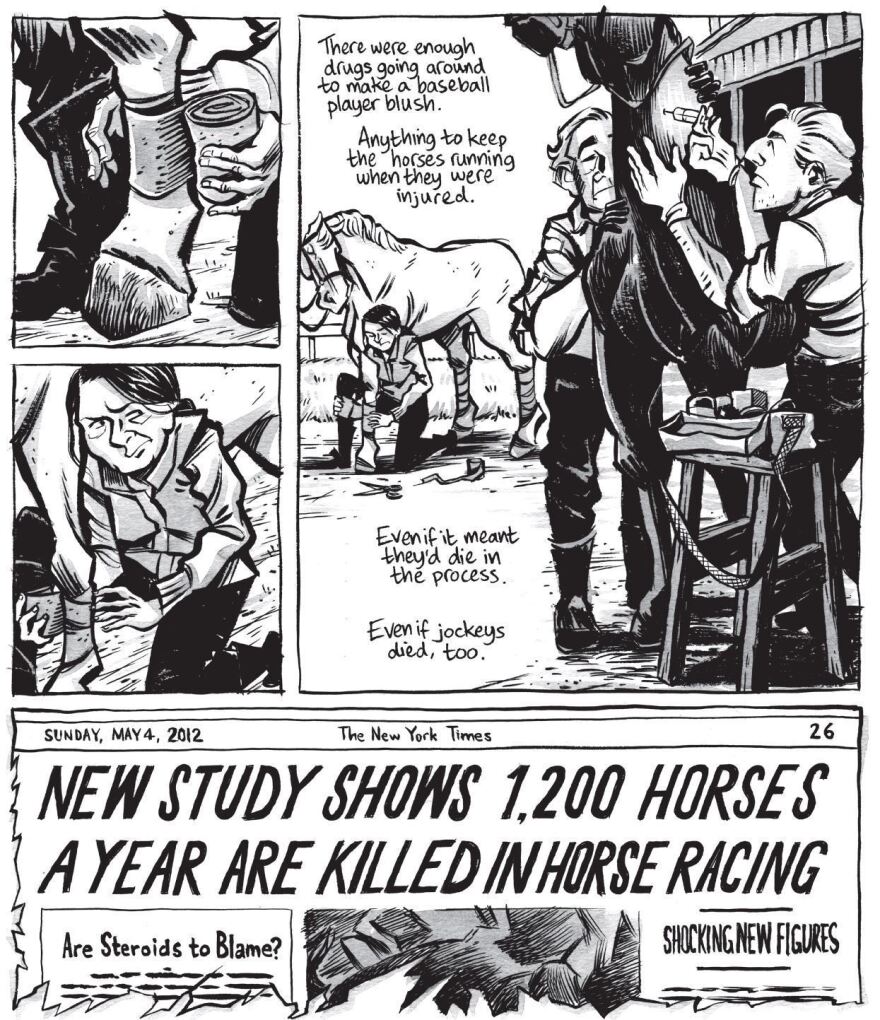

If Ruffu's recollections were true, it would mean my dad had been part of a grave problem with horse racing.

Since last December, 37 horses have died at Santa Anita during racing or training. The latest death came earlier this month at one of horse racing's most prestigious events, the Breeders' Cup, held this year at Santa Anita. Before a prime-time television audience, Mongolian Groom suffered a devastating leg fracture during the event's marquee race, the $6 million Breeders' Cup Classic. He was loaded onto an equine ambulance, driven away and euthanized.

The spate of deaths at Santa Anita, while not out of the ordinary relative to past years at the track, has drawn renewed attention to a broader racing culture that has been decried by critics for putting profits ahead of equine health. Painkillers and performance enhancers are regularly administered to horses, critics charge, which can mask injuries and clear the way for horses that are already at risk to compete. In the case of Santa Anita, a strenuous racing schedule and the effect of unusually wet weather on the track itself may also have played a role.

Last year, the sport saw 493 deaths in the United States and Canada, according to the Jockey Club's Equine Injury Database. But that number does not include deaths from injuries sustained during training.

The problem is one that Ruffu has agonized over for most of her career. She says horses are raced too young, too often, too medicated and all for the prestige and payout that come with victory.

"A million-dollar purse for one race? People are willing to throw away several dead horses trying to get that," Ruffu told me.

"Horse whisperer"

Ruffu and my dad weren't always enemies. They met in 1999 when Ruffu needed a lawyer. My father took her case.

Ruffu had filed suit against several California horse racing entities. She had been banned from the Santa Anita, Del Mar and Hollywood Park tracks for nine months, the San Gabriel Valley Tribunereported. Her unorthodox training methods and habit of distributing flyers at the track got her in trouble. The flyers said two-year-olds were too young to race in the Breeders' Cup. A judge sided with Ruffu and she was reinstated.

At the time, my dad called Ruffu a "horse whisperer."

"The people who are in control of the horse racing establishment don't know how to do things Gail's way," he told the Tribune. They parted ways amicably, and he mentioned maybe owning a horse with her someday.

In 2003, an opportunity came up when Ruffu found a horse that had already injured two stablehands.

"I heard of a horse that nobody wanted because he was a bit of an outlaw," she said, laughing. "Of course, that'd be the one for me. That's my specialty."

She called my father. He brought in three other investors and together they bought the horse for $5,000. That July, they made a deal with Ruffu. They would bankroll the horse, and in return for her labor Ruffu would get a 20% stake. They renamed the horse Urgent Envoy, after his sire, Urgent Request.

"We really put our trust in Gail," my dad recalled. "She had some kind of different ideas. Certainly in the beginning we all believed in her."

It took nearly a year for Urgent Envoy to race. Ruffu wanted to bring him up slowly to avoid injuries.

A typical horse trainer and her veterinarian might turn to medication to relax muscles, ease pain from inflammation or control bleeding. The list of approved medications for racehorses includes controversial drugs like furosemide — commonly known by the brand name Lasix — that Ruffu says are designed to hide problems and keep equine athletes in the race. Rather than treating her horse with medications, Ruffu says, she would stop training until she was sure the horse had recovered even from minor issues, so they did not become injuries.

"She told us the horse needed more time, but we were paying her monthly to take care of the horse," my dad said. "At some point we wanted to see that come to fruition."

The first race for Urgent Envoy came on June 16, 2004. It was a clear day at Hollywood Park. His jockey wore green and white. Urgent Envoy wore a red saddlecloth.

But nothing seemed to go right that day. My father recalls the jockey had trouble getting the horse into the starting gate.

"The jockey was terrified and just did a horrible job of riding him," Ruffu said.

Video of the race shows Urgent Envoy drifting away from the rail on the backstretch and swinging wide in the final turn. After nearly a year of training and at least $17,000 in costs, Urgent Envoy had finished dead last.

Showdown at Santa Anita

Urgent Envoy was scheduled to race again three weeks later. In training, he developed a sore shin, Ruffu said. It was a bump on the leg. A veterinarian recommended rest, so she pulled the horse from the race. Better to not risk a fracture.

"Your father and his partners threw a fit," Ruffu said. She continued, paraphrasing them, "We're not waiting any longer. You can just give him some drugs and run him anyway."

By the middle of July, Ruffu was out. She would keep her 20% stake in Urgent Envoy, but the other four owners had voted to remove her as trainer.

My dad denied wanting Urgent Envoy to run while injured. He said Ruffu was removed when the owners lost confidence in her owing to concerns about her training methods and the fact that she had never won a race. They were bringing on a new trainer, Richard Baltas, who is now one of the top trainers in North America by purse earnings.

"If we're going to put money into this thing, let's go with somebody who's got a little bit more of a proven track record," he said, summarizing their thinking. "Which Gail didn't have."

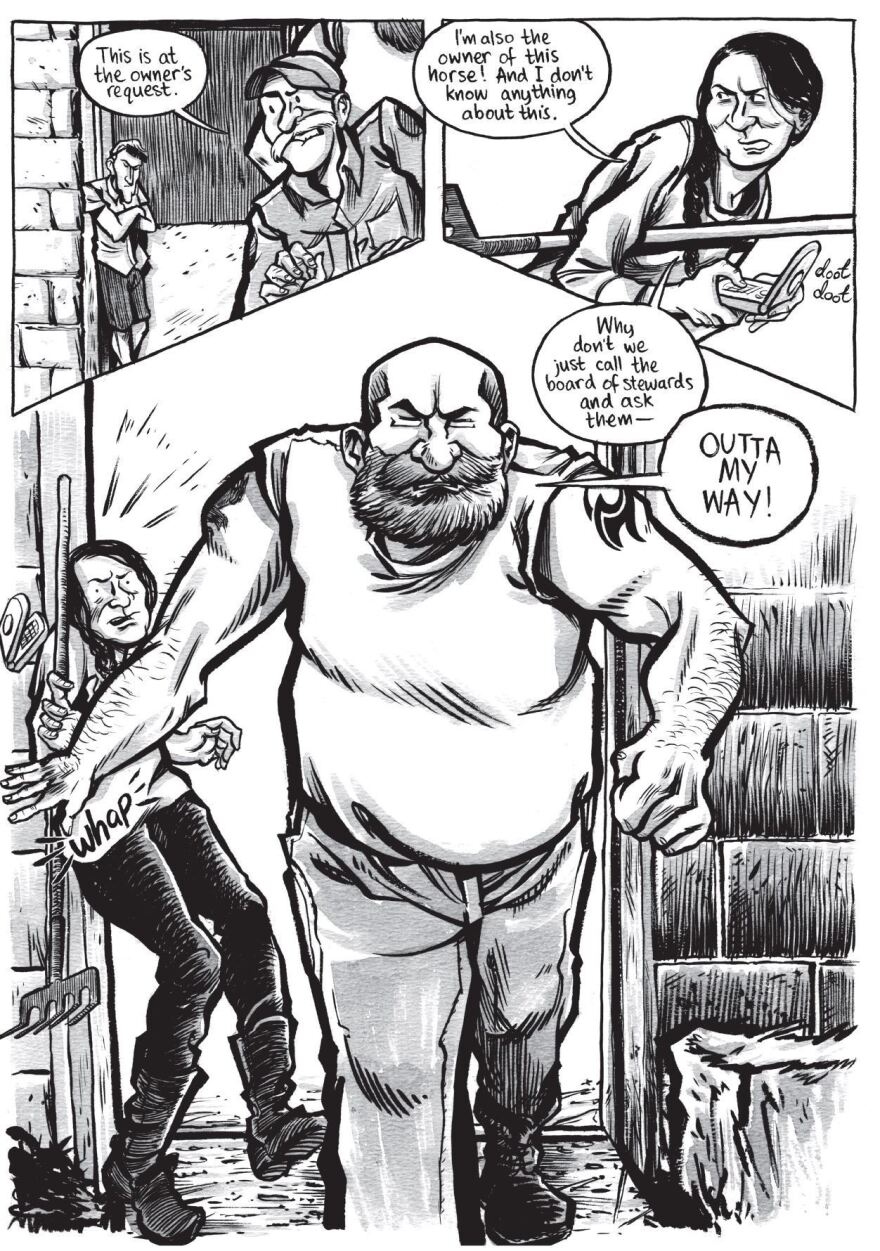

Two days after sending a letter to Ruffu delivering the news, they arrived at her barn at Santa Anita to take Urgent Envoy. The owners asked the stewards, who oversee rules at the track, to transfer him to the new trainer's barn. The stewards verbally approved, in a process Ruffu would later argue was improper. The Arcadia Police Department, track security and my dad came to oversee the transfer on July 17. Ruffu stood between them and the horse.

What happened next is in dispute.

Grand Theft Horse portrays an intense confrontation. A towering, burly man in a tank top pushes Ruffu aside and snatches the horse's reins. A man in uniform grabs Ruffu's arm. She tries to take back the reins, and in response the burly man wallops her on the arm with his fist. The uniformed man restrains her on the ground.

"They literally attacked me," Ruffu told me. "They grabbed me and held me down by my arms in the dirt while they went in and took the horse."

This version of the story floored me. Would my father just stand by while guards hit and grabbed an outnumbered woman?

When I showed my dad the scene in Grand Theft Horse, he chuckled.

"That didn't happen," he said. He recalled a security guard having to grab the reins from Gail, but no physical confrontation.

"There was no big guy," he said. "Gail wasn't arrested or apprehended, or from what I recall, even physically restrained."

There is a record of that day, but it doesn't clarify much. Ruffu filed a report with the Arcadia police. She told officers she tried to grab the horse's halter and a handler hit her arm and then walked the horse to a van. The handler, backed up by a witness, told police that when Ruffu grabbed the halter, he pushed — not hit — her arm away because the horse "began to rear and become extremely agitated," the report says.

"The gloves were off"

After Urgent Envoy was moved, the bump on his leg grew worse. An X-ray showed a stress fracture. Following a veterinarian's advice, Baltas, the new trainer, turned Urgent Envoy out to pasture. There would be no racing or training.

According to an investigation by the California Horse Racing Board, when Urgent Envoy returned from pasture in December 2004, an X-ray showed the stress fracture was still healing. Baltas put the horse on a 30-day walking regimen to rehabilitate it, the investigation found.

"I gave it the proper time off," Baltas told me.

But Ruffu was unconvinced and growing more panicked by the day.

"I began to suspect that they might be about ready to try to get an insurance policy payoff by going ahead and killing him," she said.

"That's crazy," my father said. "I would never want any person or animal to die so I could make money." Besides, he said, the owners never had an insurance policy on Urgent Envoy.

It ended up not mattering. On Christmas morning, Urgent Envoy was gone, and the owners received an email from Ruffu. It read: "Merry Christmas, boys."

"The gloves were off," my father said. "She wasn't just stealing our horse. She was rubbing it in our face."

What followed next was years of insults, investigations and legal battles. Like Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick, they chased their revenge at all costs. The Hollywood Park Board of Stewards suspended Ruffu's training license and ordered her to return Urgent Envoy. The district attorney in Inglewood, Calif., charged her with a felony count of grand theft horse.

In November 2006, a jury acquitted Ruffu. She fired back by suing the owners for breach of contract but lost that suit in 2009 and was again ordered to return the horse. She ignored the order.

By the time the civil suit was over, Urgent Envoy was eight years old — past his prime racing age.

"I always felt if we got him back, that we could turn the story around and it would win a big handicap stakes race and be the subject of a Hollywood motion picture," my dad said, smiling. "That was my hope. And after a few years, I slowly gave up that hope."

Ahab

What are two enemies willing to lose to right a perceived wrong?

For my father and his co-owners, the fight to win back a horse that finished its one and only race in last place cost, by his estimate, $100,000. Ruffu defied judges, lost her license and her livelihood for more than six years. The California Horse Racing Board let her reapply for her license in 2011.

Neither time nor distance has changed how either one feels about the past. Even now, 15 years after Urgent Envoy was taken, both told me they do not regret their actions, only that they trusted each other.

I had thought, perhaps naively, that time would have changed their perspectives, eased the animosity. Instead, having lost so much in this fight, they held on tightly to what they still had: their stories.

Ruffu doesn't think about what happened as theft. She sees it as a rescue and says she was willing to sacrifice her career because of her love for Urgent Envoy. She still has him — he's 18 now — but she keeps him in a secret location, afraid someone might steal him away in the middle of the night.

I want to believe this caution is just Ruffu being paranoid. But then I have to remind myself about how my father told me that when he heard about the graphic novel, he spoke with the only other living buyer of Urgent Envoy, his 82-year-old father (my grandfather) about getting a trailer and taking him back.

"I just think it's the right thing to do," he said. "It's not really a practical decision. I just hate to see a wrong go unpunished." He concedes, "I think she's won, and I'm a sore loser."

Talking to my dad, now 62, I could understand how hard it must have been to give up the fight. To lose your case in court, to spend years in litigation with no tangible results, to chase your stolen property and never get it back: These things can torment a successful trial lawyer.

I felt how badly he wanted to recover his dream. Still, if I ever have a Gail Ruffu of my own in life, I would hope I could learn from his story, to know when I'd lost a fight, to forgo revenge and walk away sooner.

While working on this story, I came across a video by Neri, Ruffu's cousin and the author of Grand Theft Horse, that was posted online to help promote his book.

In the video, you see Ruffu lead an enormous horse to a paddock. The horse rolls around, scratching its back in the dirt.

In the background, Neri quietly utters a code name: "Ahab, aka Urgent Envoy."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))