When Syrian artist Mohammed Al-Amari, 27, fled the country's civil war last winter he couldn't carry much. Just some clothes, and little else, he says. But he did manage to bring some "colors" with him — watercolors, pastels and even a few of his paintings.

Al-Amari and his wife didn't want to leave their home in Daraa province in southwestern Syria. They stayed for the first three years of the war, but eventually moved from their village to another one that was further from the conflict.

Last year, they reached a point when they couldn't stay any longer. Al-Amari is an elementary school art teacher. But in this village, no one was going to school.

"There was no money. There was nowhere to work, nothing to do to support myself and my family," he says. "It felt like all the life stopped."

So they made a risky 15-hour journey, driving to the Jordanian border and then walking over to join at least 3 million other Syrians who have left their country as refugees.

Now he and his wife, and their new baby, live in Za'atari Camp, a veritable city in the desert in Jordan, where more than 83,000 refugees live. Al-Amari is teaching art again as a volunteer, a few hours each day. To fill the rest of his time, he captures Syrian life – suspended — in his art.

Waiting is a major theme. What will come next, and when? This question preys on the minds of most people in the camp, says Al-Amari.

First, there's the day-to-day kind of waiting. Stuck within the borders of the dusty 5-square-mile camp, with its rows and rows of tents and trailers, Al-Amari craves a change of scenery.

"Sometimes we feel like the camp is a prison. It takes 5 months to maybe get just a 1 to 2 day pass to leave the camp, to go to Amman, the capital of Jordan, just to get out of this environment," Al-Amari says. "And that's if the local authorities approve my leaving the camp."

Then there's the bigger picture kind of waiting, a symptom of the vast uncertainty Syrians face. They have no idea when the war might end, or when they will be able to resume anything resembling normal life.

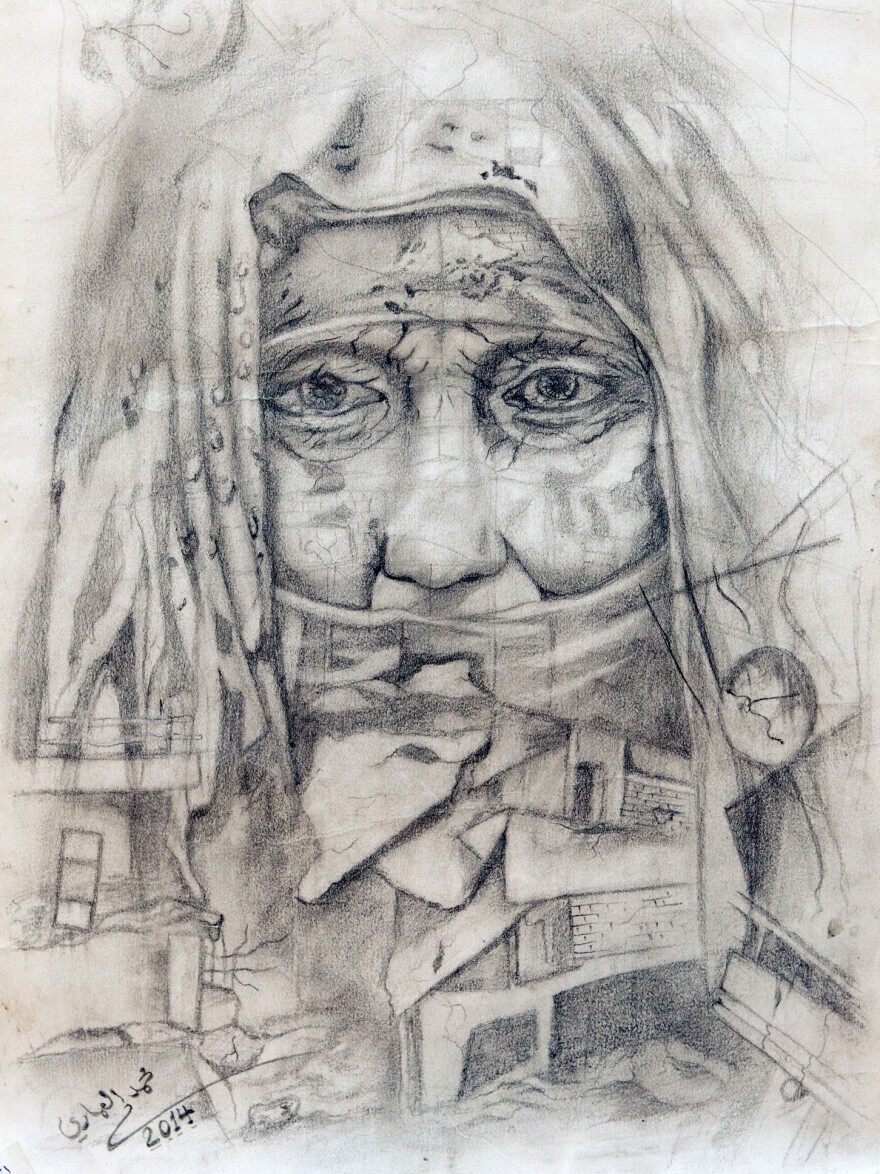

Al-Amari paints the faces of children, of women, of his grandmother, all with this one thing in common.

"They're waiting," he explains. "When I see it, when I paint it, they're waiting for a moment when they can return to the life as it was, when it used to be beautiful. We hope that the future will be more beautiful. But at the same time I feel the abyss. The path could also go for the worse. "

It's hard to stay hopeful. But it's easy to feel nostalgia.

Al-Amari met other artists in the camp. Together, they cast into their memories and draw what they remember; sometimes, iconic Syrian monuments that they fear will not survive the war, like the 2nd century Roman theater in Bosra or the ancient city walls in Damascus. All six of UNESCO's World Heritage Sites in Syria are now damaged, or in danger, or both, and many other historic sites have been destroyed.

"We're taking a picture of Syria — how it was, how the villages looked, how the cities looked" before the war, says Al-Amari.

But Al-Amari is determined to do more than just wait. He vows to make something of his time in Za'atari Camp. Many artists have worked under trying conditions, he tells himself. He and his artist friends in the camp can do the same.

"We haven't stopped [doing] what we love."

He hopes his work can touch people inside the camp, where (IRD) has supported the artists with supplies and a place to work. Camp artists have painted murals on the sides of canvas tents and staged four gallery shows.

Al-Amari says that maybe getting his images out into the world, as he has in exhibitions from Amman, Jordan, to California, will lead to some kind of change in the situation for Syria refugees.

His friend, 24-year-old artist Mahmoud Al-Hariri, agrees.

"Through our art, we've worked on sharing so many messages, trying to help life in the camp to improve, get word out about what's happening in Syria, show the pain one feels as a refugee, show sadness and devastation inside the country," says Al-Hariri.

But actual change? That's another waiting game for these artists.

"In the end, these messages, they haven't changed anything we see on the ground, and that is what's missing," Al-Hariri explains. "It's like writing a letter, and no one gives you a response."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))