Mike Nichols has a long string of classic films and plays to his credit as a director and producer, including The Odd Couple on Broadway, The Graduate on film and Angels in America on TV.

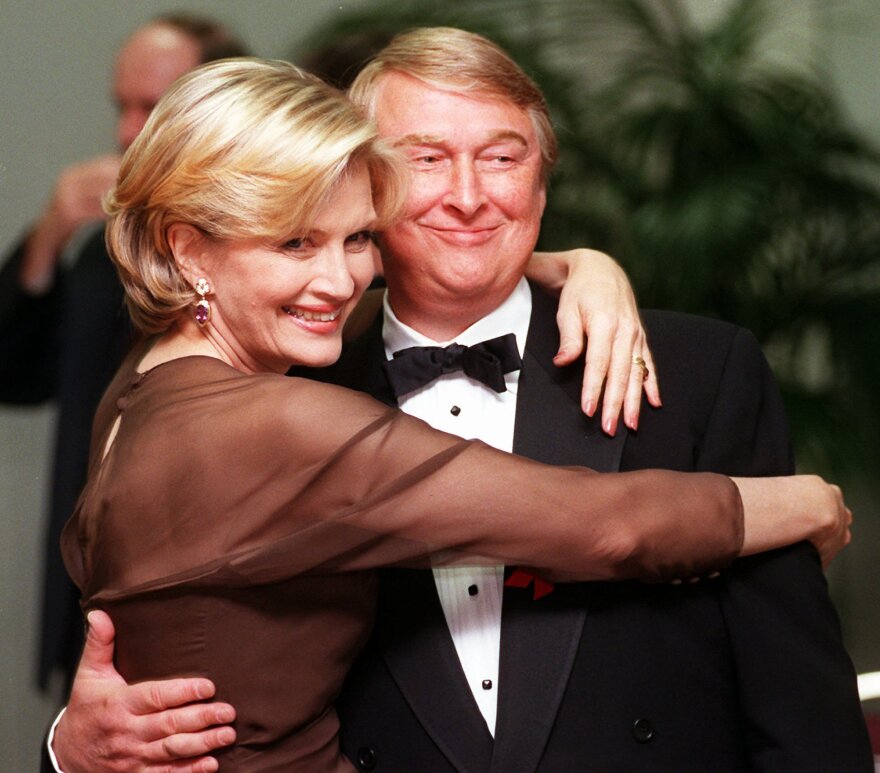

He died Wednesday night of a heart attack at age 83, acknowledged as one of the most successful artists in show business. He had earned just about every major award in entertainment, and had an enduring, 26-year marriage to ABC News anchor Diane Sawyer and a family with three children and four grandchildren.

But Nichols once said his life as the ultimate showbiz insider came from lessons learned while growing up as an outsider — emigrating from Germany to New York City at age 7 knowing little English and having few friends.

One of Nichols' greatest talents was pulling unforgettable, landmark performances from Hollywood's acting elite.

In 1966, he delivered Elizabeth Taylor as a sharp-tongued wife tearing into Richard Burton in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?"You see, George didn't have much push, he wasn't particularly aggressive," Taylor says in the film, playing the hard-drinking wife of a college professor whom she loved to torment with harsh criticism. "In fact, he was sort of a flop — a great, big, fat flop!"

In 1986, he showcased Meryl Streep slowly unraveling as she talked about her philandering husband, played by Jack Nicholson, in Heartburn.

Her character, a food writer, sits at a dinner party with her husband and friends when talk about relationships leads her to get real about her own marriage: "You sort of notice that things are not the way they were, but it's a ... a distant bell, and then when things do turn out to have been wrong, it's not that you knew all along, it was just that you were ... uh, uh ... somewhere else." The scene ends with Streep hitting Nicholson in the face with a pie intended for dessert.

But little compared to Nichols' most famous scene, featuring Dustin Hoffman in his breakout role, playing a bewildered 20-something about to begin an unwise affair with an older, married woman in 1967's The Graduate.

"Mrs. Robinson, you're trying to seduce me," Hoffman's Benjamin Braddock tells Anne Bancroft's Mrs. Robinson, the wife of his father's law partner, who is stretched out in a seductive pose that became an iconic symbol for a generation.

Nichols was a master at pushing talents like Hoffman and Streep to unexpected places. Their confused characters often highlighted thorny issues in modern life. In The Graduate, Hoffman became a symbol of baby boomers' uncertainty in a changing world, suffering through useless advice from clueless elders.

But Nichols shrugged off credit for leading actors to great performances in a 1990 interview for the Museum of the Moving Image.

"You can't direct actors very much in a movie, because if you tell them what to do, they'll be doing what you told them," he said. "What's interesting in a movie is something happening that nobody planned."

Nichols understood American culture as only someone born outside the U.S. really could.

He was born Michael Igor Peschkowsky in Germany, the son of a Russian Jew who fled the Nazis in 1939. His physician father died a few years later, leaving a wife and two sons to struggle in New York City.

In 2012, Nichols told NPR his early isolation brought a lifelong advantage.

"The thing about being an outsider, no matter what, is that there's a good part, which is that it teaches you to hear what people are thinking," he said.

"Because I learned to hear what people are thinking, quite literally, I think it stood me in good stead," Nichols added. "It's probably why I'm in the theater, because I can hear an audience. ... I could hear an audience thinking when I was in front of them."

That skill at "reading" audiences was crucial when Nichols turned from medical studies to theater in college. By the late 1950s, he had teamed with actress/writer Elaine May to create the improvisational comedy duo Nichols and May. They were all over the TV shows of the day, including The Jack Paar Show.

But performing lost its luster for Nichols, so in 1963, he agreed to direct a play by a TV joke writer. Neil Simon's Barefoot in the Park became a blockbuster success.

Suddenly, as Nichols told NPR, he realized directing was the job he was really meant to do: "To my surprise, where I never quite got how I was gonna be an actor — 'cause I don't think I'm suited to be an actor — I immediately realized that all this time I thought I was thinking about acting, I was really thinking about directing."

To my surprise, where I never quite got how I was gonna be an actor — 'cause I don't think I'm suited to be an actor — I immediately realized that all this time I thought I was thinking about acting, I was really thinking about directing.

You could spend a long afternoon listing all the classic stage, film and TV projects Nichols touched as a director or producer. The Odd Couple, Plaza Suite, Hurlyburly and Spamalot on Broadway; movies like Carnal Knowledge, Silkwood, Working Girl and Primary Colors; along with versions of Wit and Angels in America for HBO on TV.

At times, Nichols could seem like a showbiz version of Zelig. He co-produced Broadway's original, 1977 version of the hit musical Annie and gave Whoopi Goldberg a career in the mid '80s when he brought her one-woman show to Broadway.

So it makes sense that Nichols would be one of only 12 artists to become what industry types call an EGOT — someone who has won Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony awards.

But when Nichols talked with NPR about why he loved directing, grand honors weren't a big part of the equation.

"It's a wonderful job," he said. "It's exploring and excavating and analyzing all at once. And plays, especially great plays, yield their secrets over a long period of time, and that's the great excitement."

Despite passion for his work and loads of success, Nichols said, it took his fourth wife, ABC News anchor Diane Sawyer, to rescue him from depression in his mid-50s. By 2012, he was predicting his production of Death of a Salesman, which won him his sixth Tony award, might be his last play.

But a year later, he was back on Broadway, leading a revival of Harold Pinter's Betrayal; he had worked on adapting a version of the Tony-winning play Master Class for HBO with Meryl Streep before his death.

Ultimately, Nichols couldn't stay away, his passion for the work still driving him after more than five decades at the top of the industry.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))