Part 1 in a four-part series on reading in the Common Core era.

The Common Core State Standards are changing what many kids read in school. They're standards, sure — not curriculum. Teachers and districts still have great latitude when it comes to the "how" of reading instruction, but...

The Core standards explicitly require students to read "complex" material, and the fact is, many kids simply weren't doing that before the Core. What were they doing?

Teachers in Washoe County Schools (in and around Reno, Nev.) — and many districts nationwide — once used what they call a "skills and strategies" approach to teach reading. It was particularly common among poor schools where lots of kids struggled.

The idea was this: To learn how to be a good reader, kids needed to learn the skills and strategies that good readers use. Those include knowing how to find the main idea of a text, identifying key details, being able to draw conclusions, etc.

Teachers in Reno would begin each lesson by telling students the skill they'd be learning that day, says Cathy Schmidt, who taught elementary school.

"Like, today we're going to read to make inferences. Or, today we're going to predict. Or, today we're going to draw conclusions," says Schmidt.

After going over the skill of the day, teachers would typically give kids a quick summary of the story they were about to read. Then they would define the words that might be difficult for kids, says Aaron Grossman, a teacher trainer for the district who used to teach elementary and middle school.

"I would do this huge gin-up," Grossman says, revealing the story before kids could read it, with the belief that doing so would help struggling readers get through it more easily.

Next, teachers would ask students about their personal experiences with the topic of the text. If the story was about a family taking a train trip, Schmidt would ask her class: "Have you ever been on a train? Tell me about the time you've been on a train."

The goal was to engage students by connecting what they were reading with their personal experiences. Some kids would always raise their hands, eager to talk about their train trips and family vacations, says Schmidt. But others had nothing to say. Many had never been on a train or even a vacation.

Keep Kids Out Of Frustration

When kids did finally get down to reading, they wouldn't necessarily all read the same text, says Torrey Palmer, who was a literacy coordinator for the Washoe County Schools.

Teachers used a technique called "leveled instruction." Palmer describes it as "an approach to literacy in which students spend the vast majority of their time in a text that is at their reading level. So if a student is in fifth grade and they're reading at a third-grade level, they spend most of their day reading texts at a third-grade level."

Even in the upper grades, students might get different texts depending on their reading level, says Angela Orr, who was a high school history teacher.

"I was told if I wanted students to understand a primary source, I should excerpt it for the 'highest' kids," she says, "give all of the definitions of hard words for what were called the 'medium' kids. And then actually change the words to something really comprehensible for the kids that were struggling readers."

Some textbooks included multiple versions of the same text, Orr says. She remembers a particular example that bothered her:

"In one level, students were learning about the founders of our nation," she says. "In another level, the word 'founders' was taken out as if it were too difficult, and a student would read a sentence that says 'Ben Franklin started the nation.' "

The idea of all this leveling was to "keep kids out of frustration," says Aaron Grossman. This was the message from the school district, from publishers, from all kinds of experts. The goal was to make sure "you don't create a classroom environment where kids feel defeated."

The Common Core Shifts

When Nevada adopted the Common Core State Standards in 2010, Grossman recently had started a job as a teacher trainer for the school district. The message from above was that Common Core wasn't going to be a big change from the old Nevada state standards. It would mostly be a matter of adding a few things and moving material around, officials said.

"At that point, I was out," says Angela Orr, rolling her eyes. To her, Common Core sounded like one big, bureaucratic nightmare. No one was talking about why the standards were changing or what the new standards actually said.

Since it was Aaron Grossman's job to teach teachers the new standards, he decided to do some of his own research. And what he found surprised him.

The Common Core English Language Arts Standards call for three major shifts in instruction. The first is: "Regular practice with complex texts."

The idea, as Grossman learned, is to move away from focusing so much on reading skills and strategies and instead to think more about what kids read and, in particular, to make sure all students are reading text that is at their grade level. In other words, less leveled instruction.

The second Common Core shift in instruction is: "Reading, writing, and speaking grounded in evidence from texts."

Instead of using a text as a springboard into kids' personal experiences, this Common Core shift demands that students stick to the material, reading it carefully and citing evidence for all that they say or write.

One reason for this shift is that the "text to self" technique often puts kids from lower-income families at a disadvantage, says David Liben of Student Achievement Partners, a nonprofit set up by the authors of the Common Core.

Liben says that if assignments and class discussion are about personal experience, "that privileges those children who have that experience," but when students have to cite evidence from a text, they all can find something to say.

The third Common Core shift in instruction is "building knowledge through content-rich nonfiction."

In Washoe County and many other school districts, students typically read stories, especially in the early grades; there was very little nonfiction, says Grossman.

"Social studies and science just weren't being taught," he says. "In the effort to teach kids reading skills, we had kind of forgotten about the importance of a lot of other stuff."

"The New Colossus"

Grossman shared what he'd learned with his colleague, Torrey Palmer. Her reaction? "This is big, this is different!"

I believe you should know your enemy.

They asked their boss if they could bring a small group of teachers together to share what they'd learned about the Common Core and to hear what the teachers thought.

One of those teachers was Linnea Wolters, then teaching fifth grade at a low-income school in Reno.

"Oh, I'll go," she thought to herself when she got the invitation. "Because I believe you should know your enemy."

Like Angela Orr and a lot of other teachers in Washoe County, Wolters was suspicious of the Common Core. It seemed like just another education reform in a long line of reforms that, in her opinion, weren't improving schools.

Wolters agreed to try a Common Core sample lesson with her students, a "close reading" of a text. Close reading is not a new idea, but it has gained currency as a technique to teach the Common Core.

She was shocked when she realized the sample lesson focused on "The New Colossus," a sonnet by Emma Lazarus that's engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

"Keep ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she

With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

"You gotta be freaking kidding me," she said to herself, assuming the poem would be much too difficult for her fifth-graders.

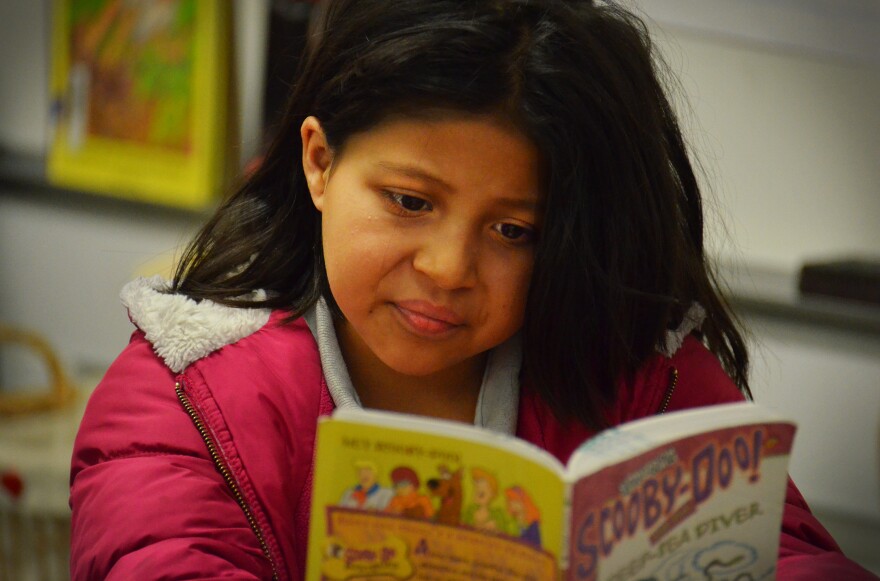

Wolters' students began by reading the sonnet on their own. Next, Wolters read the sonnet out loud, in part to help students who may have had trouble reading on their own.

After everyone had read the sonnet at least twice, Wolters guided the class through a series of "text-dependent questions and tasks." The first asked students to figure out the poem's rhyme scheme and to assign a different letter to each set of rhyming words.

"We were highlighting things and writing A's and B's and C's and D's," Wolters says. It was kind of chaos, and she wasn't sure the kids were catching on. Then a student called out, "It's a pattern!"

The voice belonged to a girl who was receiving special education services for a learning disability. She had been the first to figure out the rhyme scheme.

If Wolters had been teaching this sonnet without the Common Core-aligned lesson plan, she says she would have started by telling the students it was a poem that compares the Colossus of Rhodes, an ancient Greek statue, and the Statue of Liberty. But the new lesson plan said not to do that. The idea was to see what kids could come up with on their own, just by reading the text.

They weren't coming up with much though. At one point, the room was silent except for the sound of crickets coming from the classroom lizard cage. Then two boys who were working together raised their hands.

"Yes?" Wolters asked.

She was surprised to see the boys with their hands up. They didn't speak English at home, and they struggled to keep up in class, especially with reading.

"It's about the Statue of Liberty," they said.

The class responded with a collective "What?" They weren't buying it.

Wolters asked the boys if they had any evidence to support their idea. They pointed to the sonnet and said, "It says it's a woman with a torch."

"What do you think of Ezekial and Salvadore's ideas?" Wolters asked the class. The other students weren't sure. "Why don't you see if you can find more evidence?" she asked them.

And that got the class going.

"All of a sudden I've got kids popping off with, 'She's in a harbor!' and 'There's two cities!' " Wolters says. "They're giving me all this information, and we're highlighting. And everybody's updating their notes."

Wolters was amazed. She'd rarely seen her kids so excited about learning. And she had no idea they could succeed with such a challenging text. She couldn't wait to tell her colleagues about what had happened.

This story originally appeared as part of American RadioWorks' "Greater Expectations: The Challenge of the Common Core."

Copyright 2020 American Public Media. To see more, visit American Public Media. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))