Ariel Sharon and Yasser Arafat. It's hard to speak of one and not mention the other. They were inextricably linked by the Israel-Palestinian conflict, symbolizing a feud so enduring it's now outlasted two of its most prominent protagonists.

Neither would appreciate being compared to the other. But you could track the conflict from its earliest days to its present state by charting the lives of Sharon, who died Saturday, and Arafat, who was recently in the news following the latest inquiries into the still-fuzzy cause of his 2004 death.

Sharon, born in 1928, had his first brush with the conflict at age 1 during a bout of unrest sparked by the timeless feud over Jerusalem's most disputed religious shrine. Women and children in Sharon's farming village were herded into a barn for safety, while the men fought off Arab raiders. Sharon was unharmed, but the Jerusalem holy site — the Temple Mount to Jews, the Noble Sanctuary to Muslims – would loom large in Sharon's future.

Arafat, a man who was hard to pin down on any issue, was born that year (1929) near the turmoil in Jerusalem — according to Arafat — or in Cairo, according to his birth certificate.

Both men came of age in the first major Arab-Israeli war of Israel's independence in 1948. Sharon was a young soldier who was badly injured and nearly lost sight in one eye, while the teenage Arafat ferried weapons and took part in combat in the Gaza Strip.

They both made their names and became controversial figures in subsequent battles. Sharon's loyal supporters call him one of Israel's greatest war heroes, a natural leader in times of crisis. His fierce critics described him as headstrong and reckless, a bull of a man who embroiled Israel in wars and political battles and was repeatedly linked to the killing of Arab civilians.

Arafat, in turn, emerged as the dominant Palestinian figure in the 1960s, a position he would retain throughout his life, serving as the leading voice for Palestinian statehood among his own people, and branded an arch-terrorist by Israelis and many in the West.

One of Sharon's greatest triumphs came in the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, when he commanded Israeli forces in a daring maneuver across the Suez Canal that reversed the tide of the war with Egypt.

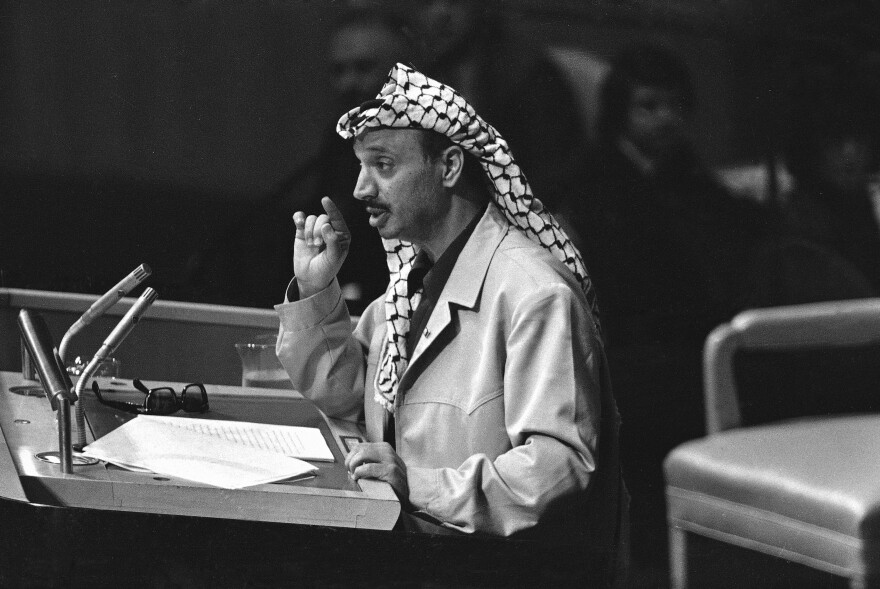

The following year, Arafat propelled the Palestinian cause to the international stage when he spoke at the United Nations, delivering perhaps his most famous remarks: "I have come bearing an olive branch and a freedom fighter's gun. Do not let the olive branch fall from my hand."

Showdown In Beirut

One of their most memorable confrontations took place in 1982, when Sharon, as Israel's defense minister, spearheaded Israel's invasion of Lebanon.

The operation was supposed to be limited to driving Arafat's Palestine Liberation Organization away from Israel's northern border. But Sharon pushed all the way to Beirut. Ultimately, Arafat and the PLO sailed out of Beirut and off to a more distant exile in Tunisia.

The Lebanon war also produced the darkest chapter of Sharon's career and became a quagmire for Israel that lasted nearly two decades.

A Lebanese Christian militia, allied with Israel, massacred Palestinian civilians in refugee camps outside Beirut, leaving hundreds dead. An Israeli commission found Sharon indirectly responsible for not preventing the slaughter, and he lost his job, effectively going into political exile for more than a decade.

In the 1990s, both men returned to center stage. An interim peace deal brought Arafat back from Tunisia. He established the Palestinian Authority, a state-in-waiting in the West Bank and Gaza.

Sharon, a leading opponent of a Palestinian state, returned to prominent government posts. He constantly pushed for the expansion of Israeli settlements, and as foreign minister, was even required to deal with his arch-rival. But when they reached a limited deal in 1998 brokered by the U.S. at the Wye River Plantation in Maryland, Sharon refused to shake hands with Arafat for the cameras.

"Shake the hand of that dog? Never," Sharon told Uri Dan, an Israeli journalist who chronicled Sharon for decades.

Sharon's Provocative Visit

A couple years later, on Sept. 28, 2000, Sharon took the highly provocative step of visiting the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, the most sacred place in Judaism. Israeli politicians had long avoided it because of its political sensitivity — it's also one of the holiest sites in Islam.

Palestinian rioting erupted the next day, which turned into a full-scale uprising, setting the stage for another major confrontation between Sharon and Arafat.

Sharon's many critics accused him of sparking the violence. Yet Sharon's stock soared among Israeli voters and he became prime minister in February 2001 elections with a pledge to crush the Palestinian uprising, or intifada.

"It's a war going on here," Sharon said just before he was elected. "You have to take your enemy out of balance by presenting him daily with new problems. He should be defending himself rather than attacking us. I'm not speaking about the theory — I've done it."

Sharon's office in Jerusalem and Arafat's compound in Ramallah were less than 10 miles apart. Yet their communication was limited to bitter recriminations as the Israeli-Palestinian fighting entered its deadliest period ever.

In March 2002, after a wave of Palestinian suicide bombings, Sharon ordered a major military invasion of the West Bank, taking over Palestinian towns and pointedly keeping Arafat confined to his one-square-block compound in Ramallah, where he would remain until the final days of his life.

After pursuing Arafat for decades, Sharon now had him as a virtual prisoner.

Sharon Removes Jewish Settlers

Yet a year later, Sharon faced a dilemma.

His most important ally, U.S. President George W. Bush, wanted to relaunch Israeli-Palestinian peace talks in the summer of 2003.

Sharon knew he needed Bush's support and didn't want to alienate the American president. The Israeli leader also knew that most of the world favored a resumption of peace talks. Yet Sharon had no intention of negotiating with Arafat.

After stalling for a few months, Sharon came up with his own plan that stunned supporters and critics alike. He said he would withdraw all 8,000 Jewish settlers from the Gaza Strip, the very place he had encouraged them to go for decades.

This seemed wildly out of character for Sharon, the master builder of settlements, but it served several of his purposes simultaneously.

First, it greatly eased the pressure to negotiate with Arafat. In one stroke, Sharon turned the focus onto his Gaza withdrawal plan. President Bush's "road map" for peace was effectively shelved.

Arafat complained loudly that Sharon was acting unilaterally in Gaza and was refusing to negotiate, which was true. But Sharon could easily brush this aside because now the U.S., along with Europe and much of the world, supported Sharon's withdrawal plan.

Sharon didn't relish the thought of uprooting Jewish settlers, but he believed that by giving up the small Gaza settlements, which had become a huge burden for Israel's security forces, he could protect and consolidate the much larger settler population in the West Bank. The West Bank settlers today number around 350,000 – or more than 40 settlers for every one that was removed from Gaza.

The Conflict Outlasts Both Men

As Sharon prepared for the Gaza withdrawal, Arafat fell seriously ill at his Ramallah compound. Sharon permitted him to travel to a French medical hospital, where he died days later on Nov. 11, 2004.

After decades of rivalry, Sharon had outlasted Arafat.

The Israeli leader went ahead with the Gaza withdrawal in the summer of 2005. The bruising internal Israeli political battle left Sharon drained.

In December 2005, just a year after Arafat's death, Sharon suffered a mild stroke, but soon returned to work. On Jan. 4, 2006, a major stroke put him into a coma from which he never awoke.

The Arab-Israeli conflict has produced many memorable figures, and Sharon and Arafat, as much as any two men, shaped the conflict that exists today.

Arafat brought the Palestinians to the cusp of statehood, though it presently remains beyond their grasp. Sharon was a major figure in Israel's wars, the man most associated with the Israeli settlements, and he built the West Bank barrier that remains a major bone of contention.

Peace talks are once again the order of the day. Yet the conflict grinds on, having outlasted Sharon, Arafat and many others who have taken part in its countless battles over the years.

Greg Myre, the international editor of NPR.org, reported from Jerusalem from 1999 to 2007 and is the co-author of This Burning Land: Lessons From the Front Lines of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))