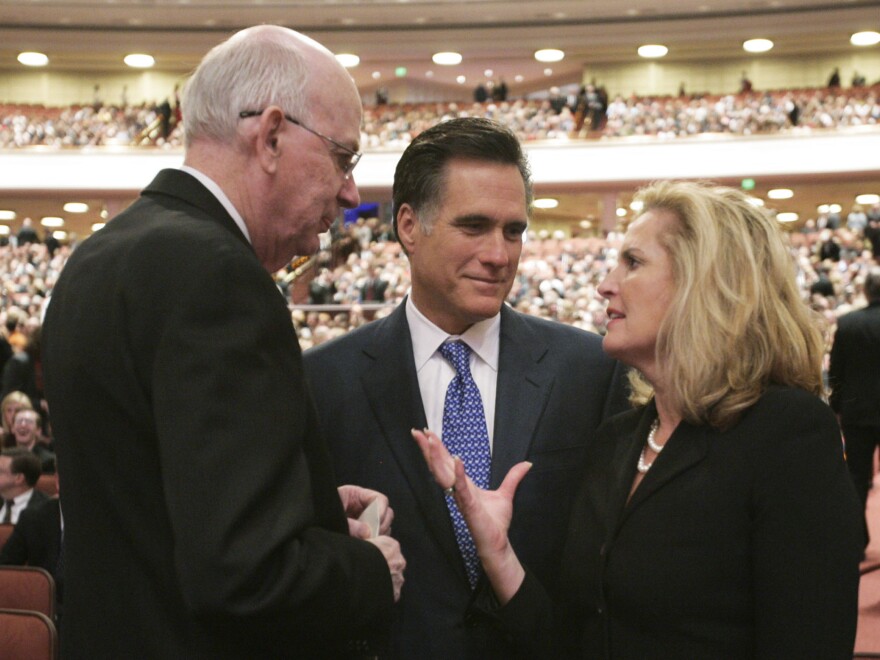

Win or lose on Election Day, Republican Mitt Romney has already made history as the first Mormon to win a major party presidential nomination.

But has his race for the White House changed Americans' perceptions and stereotypes of the small, insular but fast-growing religion, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints?

And, by extension, has Romney affected how Mormons view their place in the nation?

Two noted Mormon experts we turned to as the 2012 presidential campaign draws to a close said that they see national perceptions of the religion emerging largely unchanged by Romney's run, but that perhaps it has helped Mormonism shed a bit of its mystery.

"I think the general reader has become more educated about Mormonism, and some of its reputation for strangeness has worn off, though it retains its deserved reputation for difference," says Kathleen Flake, author of The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle.

"Certainly, more people will have heard of it," says Flake, a Vanderbilt Divinity School American religion professor. "But with few exceptions, what they have heard pro and con seems remarkably similar to what was being said in the 1970s."

Matthew Bowman, author of The Mormon People: The Making of An American Faith and an assistant religion professor at Hampden-Sydney College, says he has come to a similar conclusion.

"The main obstacle to integration for any religion in the U.S. is, simply, size," Bowman says. "Fear and antagonism toward Catholics in America declined in tandem with the growth of the Catholic population in the U.S."

"Mormons," he said, "still make up only 2 percent of the American population; they likely still have hills to climb."

A Pew Research Center survey of American Mormons released in January, well before Romney captured the GOP nomination, explored the church members' vision of themselves, and how they believe they are perceived by non-Mormons. We also asked Flake and Bowman to help us discern how the past 10 months may have affected attitudes reflected in the study.

Romney isn't the first Mormon to seek the presidency. In fact, nine others sought the nation's highest office before Romney. They include Mormon founder Joseph Smith in 1844, and Romney's father, George, in 1968. Additionally, former Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman made a brief run for the GOP nomination this year.

Here's what we wanted to know, and what Bowman and Flake had to tell us:

NPR: The church, along with its attributes of community and giving and focus on family, has also been consistently portrayed as inward looking, and with a complicated history that includes polygamy, discrimination and accumulation of wealth. Has Romney's run done anything to change that, and, if so, what and how?

Bowman: Romney, unfortunately, tends to embody some of the more benign stereotypes: wealthy, awkward and so on. What his run has done, however, is bring attention to the diversity of Mormons in the United States. The variety of Mormons who have become prominent in the media, and Romney's occasional head-butting with his co-religionist [Senate Majority Leader] Harry Reid [the Nevada Democrat], have done a fair amount to refute the great myth of Mormonism: that it's a monolith.

Flake: Probably not. More than sound bites, drive-by photo ops and editorials are needed on these complex issues and common canards. This is not to fault the press. Electioneering is not given to much more than this and most Americans have never had any patience for theology.

NPR: The question of whether Mormonism is a Christian religion still divides the general public and has made Romney's path to the Republican nomination even more historic. Mormons say they feel hostility from evangelical Christians, an important part of the GOP base, and they should, given Pew's findings. We're now seeing numbers that suggest [a] party highly motivated to support Romney. Politically, what have you seen happen over the past 10 months that brought this part of the Republican electorate around?

Bowman: I don't know that the electorate has, actually, changed much. Evangelicals are rather bitterly divided over Romney, but that's been true from the beginning, and I suspect most of that faction of evangelicals who make up the religious right are in the religious right because of their politics, and will swallow hard and vote for the candidate who best matches those politics. That said, there is probably some small faction who are just going to stay home.

Flake: Romney's nomination necessitated the silencing of evangelical anti-Mormonism. Other explanations, it seems to me, underestimate their antipathy — racial and religious — of the present administration and their fear of a second term .

NPR: There are still people uncomfortable with the notion of a Mormon president; some cite the Mormon belief that the Constitution, and, with it, democracy, were "divinely inspired," as Richard and Joan Ostling wrote in "Mormon in America." If Mitt Romney wins the White House, how do you see his faith informing his decisions? How is this different from John F. Kennedy becoming the first Catholic president?

Bowman: Romney is far different from Kennedy. Kennedy's election marked the culmination of a long process of Catholic integration in the U.S. Romney's run is still early in Mormonism's integration. Of course Romney's faith might inform his decisions as president, just as the faith of any believer informs the ways they live their lives and do their job. Mormon faith in American exceptionalism, though it differs in origin from that of, say, conservative Protestants in America, is not so different than that held by, for instance, Ronald Reagan or George Bush, which means it's well within the spectrum of American politics. Some might be worried, as some were worried about Kennedy, that the leader of their faith would dictate the decisions of the president. Kennedy specifically repudiated this possibility; Romney has not. But in practice it's extraordinarily unlikely that the LDS leadership would do something like it; they are well aware of these suspicions, have been since the early 20th century.

Flake: Our times and his party, not Romney's faith, would mark the difference. Whereas Kennedy could satisfy his electorate by pledging separation from religion, Romney will have to offer special status to religion, as promised in his 2007 speech on the subject. As for the extent to which Mormonism will inform his decisions, the campaign seems the best measure of that. If you can find Mormonism in his current policy decisions, you will see it in future ones.

NPR: Nearly half of the Mormons surveyed by Pew said that there is "a lot of discrimination" against Mormons. In what context do you think Mormons experience discrimination, and how might Romney's run, and potential presidency, alleviate the perception and/or the condition?

Bowman: There's a lot of residual sense of persecution within Mormonism, deriving, of course, from the church's historic experience in America, but also from the rather unending barrage of evangelical countercult organizations that target Mormonism. Regardless, I think a lot of Mormons were rather distressed at much of what came out in the past couple of years: [Former Arkansas Gov.] Mike Huckabee's comments in Romney's first run, the Book of Mormon musical, and so on. What's interesting is that while traditionally anti-Mormonism presented Mormons as a dangerous threat to America, more recently, Mormons have been presented as naive, uptight, and unbearably nice. Caricatures of Romney himself certainly fall into the latter category, and thus will probably reinforce rather than eliminate stereotype.

Flake: "Discrimination" is an inapt term for the treatment of Latter-day Saints. In America, they are simply too white and middle class to deserve its use. More accurately, they are ridiculed and stereotyped from the right and left as wrongly religious or too religious, respectively. This estimation of them as presumptively threatening or foolish will, I expect, continue to diminish as they become better known. If Romney is elected, press coverage of him may lead to greater familiarity with his religion. At least, this will be the case if the press continues to try to explain his politics in terms of his religion.

NPR: Another interesting Pew finding was that only 30 percent of Mormons said that others see Mormonism as mainstream, yet 63 percent said acceptance of Mormonism "is rising." Where do you think that Mormons find this rising acceptance, and has Romney specifically done anything the 10 months since the survey was released to make Mormonism "mainstream"?

Bowman: To many Americans the problem is that Mormons are "too" mainstream, with their white shirts, conservative haircuts, and so on. They're a poor fit in an America that increasingly prizes diversity and informality. I don't know that Romney has specifically tried to persuade Americans that Mormons are mainstream because, in fact, many Mormons "feel" mainstream, even if other Americans don't think so. Romney has almost certainly had about zero angst over whether or not his religion's particular theology might prevent him from running for president, just as Stephenie Meyer (author of the Twilight series) probably sees no conflict between writing about vampires and going to a Mormon chapel on Sundays. That, I think, may account for the discrepancy in this poll: Mormons are talking about how they perceive others perceiving them, not about themselves.

Flake: Latter-day Saints probably see improvement in the mere fact of the general public's attempt to understand them as they see themselves, not simplistically as their sectarian antagonists have caricatured them. Romney's refusal to be drawn into theological discussions has probably helped to direct the conversation away from historically internecine debates and toward understanding his church as a contemporary social phenomenon.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))