Sign up for TPR Today, Texas Public Radio's newsletter that brings our top stories to your inbox each morning.

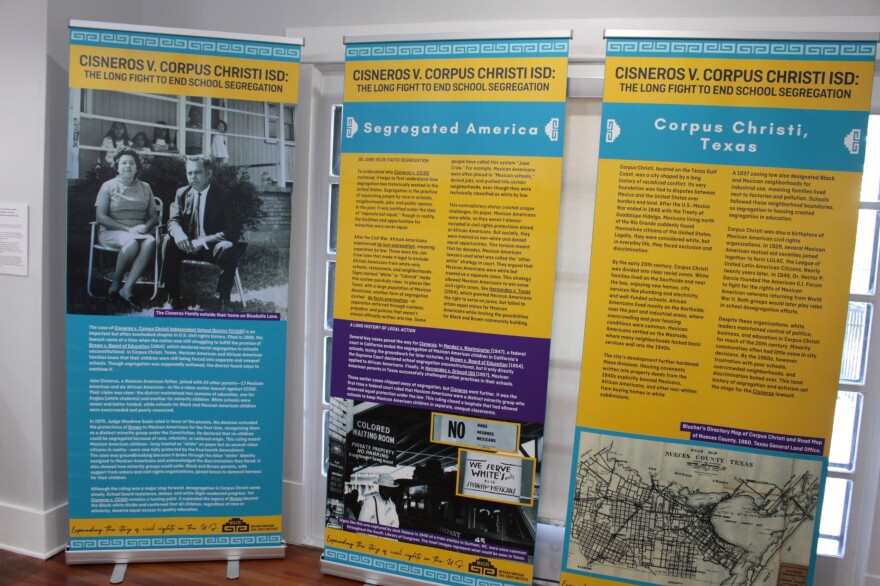

The Mexican American Civil Rights Institute (MACRI) recently opened their latest travelling exhibit: "Cisneros v. Corpus Christi ISD: The Long Fight to End School Segregation." It will be at MACRI until November 26, 2025.

Although the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education court case desegregated schools in the United States, schools found a loophole to continue segregation. Legally, Mexican Americans were considered white. This allowed school districts to put Mexican American and African American students in separate facilities from their white peers. The lawsuit claimed that the white schools had better resources, facilities, and activities.

The Cisneros v. Corpus Christi ISD court case revolves around a group of about two dozen parents —17 Mexican American and six African American — who sued Corpus Christi ISD in 1968 for not integrating their children. It is marked as one of the first times that a coalition of African American and Mexican American parents came together for a civil rights cause.

The case is named after José Cisneros, the parent who led the case. Architectural historian Steph McDougal found Cisneros’ 1970s home nearly untouched in Corpus Christi and thought it would be a great national register nomination. The National Register of Historic Places is a federal program that recognizes sites of historic importance in the United States. Less than 2% of National Registers are related to U.S. Latino history. McDougal and MACRI’s Executive Director Sarah Zenaida Gould collaborated to pursue the national registration nomination. They added an exhibit component as well. Isabel Araiza, a sociologist from Corpus Christi Del Mar College, joined in to help research Cisneros’ impact.

The exhibit is made up of eight panels that can be easily transported to other locations for exhibition. The first panel begins with an image of Cisneros’ house on Blue Bell Lane in Corpus Christi, since the home is what led MACRI to the court case. Before jumping into the case, Gould said they wanted to provide some historical context on segregated America. They explain "de jure" (what is established by law) versus "de facto" (what exists in practice) segregation. The exhibit also breaks down previous court cases that address Mexican American segregation such as Hernandez v. Driscoll, which was fought by James DeAnda, the same lawyer who defended Cisneros. Gould said providing information on previous segregation cases is important because they helped build the Cisneros v. Corpus Christi ISD lawsuit.

The third panel of the exhibit has a map that shows the race relations of Corpus Christi. Gould explains the layout of the coastal city.

“It is a city that was very much segregated —Mexican Americans on the west side, African Americans on the northern side, and then whites along the water and sort of the southern side of the city,” Gould said. “So very much a segregated city and followed some of the patterns of labor in the city. But it was something that if you grew up there in that era, you would have known sort of what part of town you are supposed to be in.”

The exhibit explains that despite the visible segregation, there was an active movement in Corpus Christi regarding the rights of Latinos. The oldest extant Latino civil rights organization in the country, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), was founded there in 1929, as was the American GI Forum (AGIF), founded by Hector P. Garcia, who actually consulted in the Cisneros court case. AGIF formed after World War II to help Mexican Americans access their GI Bill, along with other resources that they had a right to but were being deprived of because of discrimination.

The following panel discusses the African Americans' civil rights movement hitting its peak in the late '60s. The passing of the voting rights act and the civil rights act created momentum for the Chicano movement.

The parents involved in the case were members of the Steel Workers Union, which gave rights to the workers of the port in Corpus. The parents asked the union for support in the court case and the union provided the money to file the lawsuit. They also created a coalition with MALDEF, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, and the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. There’s a photo in the exhibit of the families involved in the case; a group of Mexican Americans and Black people in suits and ties coming together to fight for their children's rights.

From there, the exhibit leads into a panel titled “the legal question.” which declares that the heart of the court case was the question of if Mexican American children were being denied equal protection under the constitution. This section examines whether the segregation was intentional.

Judge Woodrow Seal determined that Brown v. Board of Education already determined that education must be available to all students on equal terms and concluded that Brown applies to Mexican American students in public schools.

The process of desegregation did not come without controversy. Some white parents simply did not want their children to go to integrated schools. Because of this, there was a lot of white flight, meaning white families left inner-city Corpus Christi and moved to the Suburbs where schools lean majority white because that is who lived out in the suburbs. Mexican American parents worried about how this reality would impact their children’s commute to school, since integration meant they would have to go to a school halfway across town. They also worried about potential bullying and isolation.

“I will just say, I think when you look at the whole history of integration of schools, very few communities had an easy time with the integration process, both because of white flight and because of concerns from parents of color about the safety of their kids," said Gould. "And yet, I think we understood it was not right that students were being forcibly segregated.”

The final panel of the exhibit is titled “Legacy,” which discusses the impact of the case on the Corpus Christi community. The main takeaway was that, for the first time, Mexican Americans were recognized by the courts as a protected minority, becoming an important precedent for future cases involving the desegregation of schools in the south. It also demonstrated that Mexican Americans and African Americans can work together to take on segregation and discrimination, and that coalitions that had never worked together before could do so and succeed.

The exhibit will be on display at the MACRI visitor center until November 26. Soon after, it will travel to Corpus Christi.