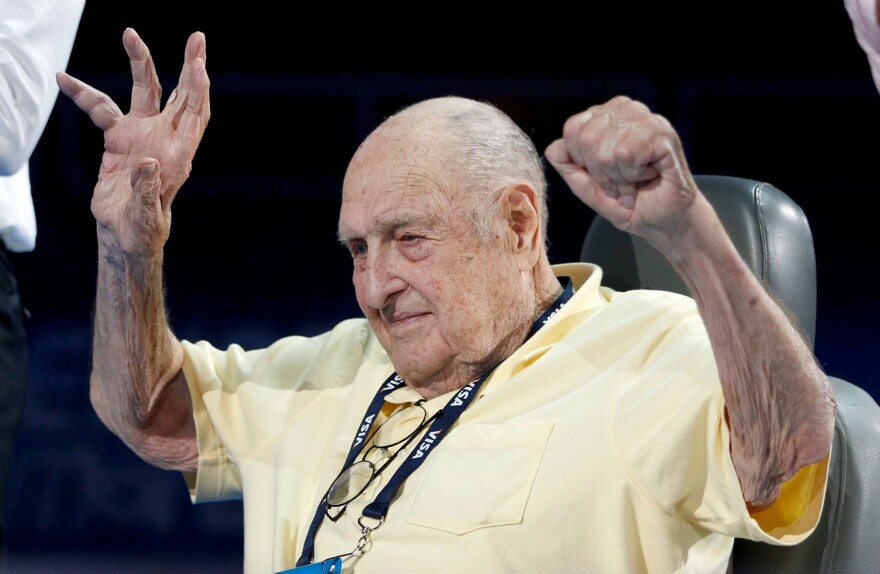

Adolph Kiefer, the 100-meter backstroke champion at the 1936 Berlin Games, died Friday at the age of 98. He was America's oldest living Olympic champion.

According to the U.S. Olympic Committee, Kiefer broke 23 records in all, including every backstroke record. But his grandson Robin Kiefer says, the swimmer considered his greatest achievement to be his work with the U.S. Navy during World War II. It was a time when many sailors were drowning after shipwrecks, and Kiefer helped develop a curriculum for teaching sailors to swim, as well as the "victory backstroke," which is credited with saving thousands of lives.

"When he woke up in the morning, he was a swimmer, and when he went to bed he was a swimmer, and he dreamed about swimming and saving lives," Robin Kiefer said.

There was some doubt though, as to whether Adolph Kiefer and the other athletes would go to the Berlin Olympics at all. In a 2014 interview with his alma mater, the University of Texas, Kiefer explained that both the United States and England were considering a boycott of the German Olympics — "the Nazi Olympics." In the end though, the U.S. team did go, and Kiefer met Hitler and shook his hand. He told the University of Texas in 2014, if he had known then what he knows now, "I would have thrown him in the pool. But how do you know?"

There were no Olympic Games held in 1940 or 1944 because of the second World War, so what might have been a longer Olympic career changed course. Kiefer went to college, and then joined the Navy, where he rose to the rank of Lieutenant. He married his wife Joyce, who would be his business partner and his partner in life for more than 73 years, until her death in 2015. His grandson says, the couple opened their backyard swimming pool in Northfield, Il, so that the neighborhood kids could learn to swim.

Together, Adolph and Joyce Kiefer built , a swimming equipment company that he is said to have joked sold "everything but the water." They developed the nylon swimsuit, and the first non-turbulent racing lane, which helped to level the playing field by making it harder for swimmers to "ride the wake" of a swimmer in another lane.

"He didn't look back. He was always looking to the next new thing," said Bruce Wigo, the president of the International Swimming Hall of Fame. Wigo says that later in life, Kiefer was focused on helping elderly people use the water for exercise.

Even after he was confined to a wheelchair due to neuropathy, Kiefer continued to swim everyday. Wigo said that Kiefer told him in the water, he felt "human" again. In 2014, at the age of 95, he was featured by the Chicago Tribune in an article and accompanying video. He told the camera, "The feeling of swimming, of being independent, the feeling of relaxing in the water, is the greatest feeling in the world. Everybody should experience it."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))