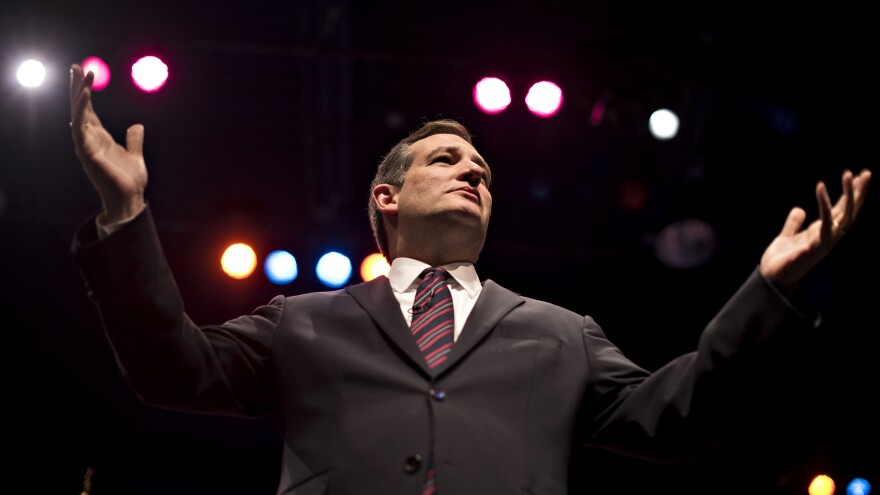

Ted Cruz has one of the most overtly religious stump speeches on the Iowa campaign trail.

In Emmetsburg, Iowa, Friday the Texas senator quoted the Bible and exhorted his supporters to pray "each and every day" until Election Day.

"He's real," said Bobbie Clark, a Cruz supporter from Algona. "There's something there. There's substance behind it. It's not just talk."

There's a big reason Cruz and others are making that kind of pitch here days before the first votes cast in this presidential campaign season — Iowa's " evangelical voters" have carved a well-worn path for past Iowa winners. Rick Santorum in 2012 and Mike Huckabee in 2008, for example, won them over and won the caucuses.

As with the fractured 2012 field, it's not at all clear who will win this year's Iowa GOP caucuses. But it seems to be a two-man race — between Cruz and Donald Trump.

In the final Des Moines Register/Bloomberg Iowa poll before the caucuses, Trump leads Cruz 28 to 23 percent overall. But Cruz leads with evangelicals, 33 to 19 percent.

That could bode well for Cruz Monday night, if those evangelical voters turn out in high numbers like in year's past. But while Cruz is ahead with those voters, he doesn't have the kind of dominant lead with the group that can ensure victory.

J. Ann Selzer, the pollster who conducted the poll, said Trump's lead shrinks to 1 point over Cruz if religious conservatives match 2012's turnout of 55 percent of the electorate.

In that sense, this year's race is looking more like 2012 than 2008. In 2012, Iowa evangelicals' support was relatively divided. Entrance polls showed Santorum with 32 percent of evangelicals' support, compared with Ron Paul's 18 percent (remarkably close to the Cruz-Trump split that this latest poll shows). Three other candidates each took 14 percent. Santorum went on to win the caucuses by just 34 votes over Mitt Romney. Paul finished a strong third.

Meanwhile, in 2008, Huckabee had a far more commanding lead with these voters. He took 46 percent to Romney's 19 percent — and they made up 60 percent of the electorate. All that added up to a solid 9-point win for Huckabee over Romney.

While all of the Republican candidates are Christians, some, like Cruz and retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson, have made their faith a more central part of their message than others. At the Cruz event in Emmetsburg, his supporters said they appreciate his faithcentric campaign.

But while faith plays a part in how many voters choose a candidate, some say they feel manipulated by blunt appeals to their Christian identity.

"I think sometimes they're just giving me lip service," said Dave Mouw before a Jeb Bush campaign event in Sioux Center, Iowa. "They're telling me what I want to hear. You can usually tell by a guy if he means it or not."

As of Friday, Mouw was torn between a few candidates — Bush, John Kasich, Rand Paul and Marco Rubio. Meanwhile, Mouw said, there's one candidate who is not winning him over.

"I don't need Donald Trump reading me a Bible verse," Mouw said.

Other voters echoed that ambivalence toward religious appeals.

"I don't give support simply by quoting the Bible. I want to see it lived out in the policy," said John Lee, a pastor in Sioux Center. "I'm not electing a pastor in chief. I'm electing a commander in chief."

Lee doesn't know whom he will vote for in Monday's caucus, but he knows whom he won't be supporting: Ted Cruz and Donald Trump. Lee said his Christian beliefs led him to oppose their hard-line immigration stances — policies that are part of what he labels "callous conservatism."

Sioux Center, where Lee and Mouw came out to see Bush speak on Friday, is in the heart of Iowa's conservative Christian northwest corner, which helped push to victory Huckabee in 2008 and Santorum in 2012.

For context on just how conservative Sioux County is — in the 2012 general election, around 47 percent of Iowans voted for Romney, but nearly 84 percent of Sioux County did.

Though Lee acknowledges he is not intimately familiar with his congregation's political views, he said his "unofficial sense" is that they are divided among several candidates, especially Rubio, Santorum, Carson and Cruz. Meanwhile, of the 600 to 700 people who attend on Sundays, he knows of only one who supports Trump.

So while candidates may make religious references and show off their family Bibles to win over Iowa's Christian vote, that approach can go only so far. Many evangelical voters simply aren't first and foremost religious voters.

Nancy Van Roekel from Hinton said her faith "definitely" plays into her decision to support Bush but that his main appeal comes from his consistency and experience.

Indeed a big ( huge, even) part of Trump's appeal stems from his "outsider" status, with his promises to drastically change Washington. In fact, many white, self-described evangelicals support Trump despite also not seeing him as very religious, as NPR's Tom Gjelten reported.

Trump's message has driven him to the top of the Iowa polls, and some are predicting it could push droves of first-time caucusgoers out the door on Monday night.

Lee is one such person. He has never caucused before — caucusing requires choosing a party, and as he put it, "I don't think God belongs to either party." But Trump has inspired him — albeit not in the way Trump might hope.

"This year I will [caucus]," Lee said, adding, "With Trump leading in the polls, I feel like it's a status confessionis time," Lee said, using a term referring to a point when the church has to take a position on an issue.

"I have to, as a pastor, say, 'This is not who we are.' Otherwise I sit them out."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))