It began with a ritual circumcision for a teenager in South Africa, from the Xhosa tribe. And it ended with the world's first penile transplant, completed in December and disclosed last week.

So far, it looks like a success. After the nine-hour procedure, Andre van der Merwe, the surgeon who led the transplant team at South Africa's Tygerberg Hospital, was relatively confident that his patient, then 21, would eventually have a fully functioning penis. In time. Van der Merwe reckoned that it would take a couple of years for that to happen.

But just five weeks later, the patient informed him that not only was he achieving erections, but he had also engaged in intercourse. "I was shocked. I didn't know what to say," recalls van der Merwe, adding that he also feared that the early action might lead to a blood clot.

So far, the patient — who three years ago had his penis amputated because of complications after his circumcision — is in robust health and his transplanted penis is still fully functional, the surgeon says.

The operation is the first of 10 planned in a pilot study, a joint effort between Stellenbosch University — where van der Merwe is chief of the urology division — and Tygerberg Hospital in Cape Town, in South Africa's Western Cape province. The aim is to establish a safe medical procedure that could routinely be used in the country's hospitals.

Routinely? Unfortunately, yes.

The practice of traditional, ritual circumcisions is ingrained in the culture of South Africa's more than 8 million-strong Xhosa tribe. In a rite-of-passage ritual called ukwaluka, young men around 18 years of age are circumcised by a traditional practitioner called an incibi. South Africa's late president, Nelson Mandela, went through the ritual as a teen and later described the resulting pain as akin to "fire shooting through my veins."

In some cases, pain is only part of the problem. Traditional circumcisions can go awry. Complications include sepsis, mutilation, gangrene and excessive bleeding.

Often the only remedy is amputation — that's what happened to the young man. According to Stellenbosch University, experts estimate that each year at least 250 penises are amputated in South Africa alone as a result of botched circumcision.

No one is trying to put an end to the ritual. "It's part of their culture," explains Dr. Dimitri Erasmus, Tygerberg Hospital's CEO. But the medical community is offering advice on blades and techniques and supplies such as dressings and anesthetics. They're also offering the option of inviting young men to go to a medical clinic for the circumcision, then return to their village to complete the ceremony.

Msokole Qotole, an official at the Western Cape Department of Health who works with traditional practitioners, says some of them are starting to accept the medical community's help. "They are keen to do safe circumcisions."

But Qotole is proceeding cautiously. The Eastern Cape province in 2001 enacted a law to regulate ritual circumcisions but to little effect. Qotole says he fears that laws could backfire and worsen the problem. "Do you want to drive things underground with regulations?" he asks. "No."

If van der Merwe is successful in developing a routine penile transplant procedure, it could offer hope for the young victims.

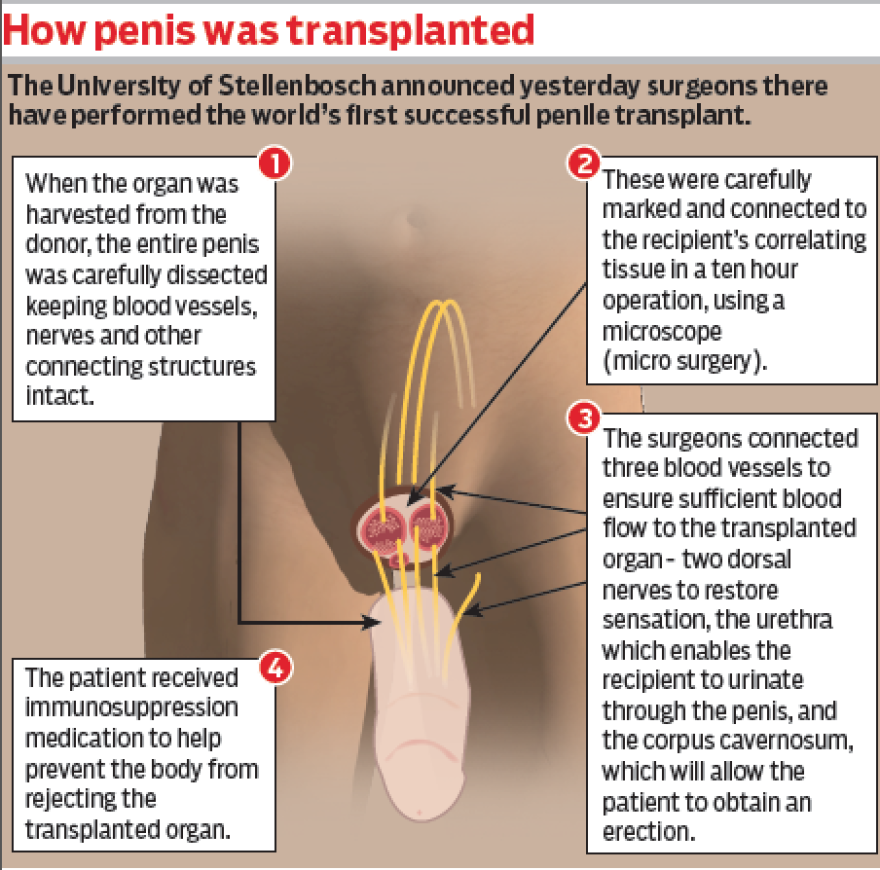

The December operation used microsurgery techniques to precisely align the blood vessels, nerves, urethra and tissues — particularly the corpus cavernosum tissue that enables erections — between the recipient's stump and the harvested penis. One issue that prolonged the surgery, van der Merwe says, was the discovery of how much scar tissue there was on the stump. To work around it, the team rerouted an abdominal artery to the organ.

One of the most time-consuming hurdles was finding a donor. Eventually, they obtained the organ from a young man dying from a brain injury but still on life support. His family donated several of his other organs, including his heart, lungs and cornea.

Van der Merwe is confident that, in part because of the positive publicity the surgery has elicited, finding future donors will be easier. But he admits that there may have to be an upper age limit on donors — just as there is for kidney transplants — and surgeons will have to be confident that donors did not suffer from erectile dysfunction.

For recipients, there is the never-ending risk that their body will reject the transplant. "It is a lifelong problem," van der Merwe says, and a recipient will always have to take immunosuppression drugs. But, he adds, in most cases, the longer a body does not reject a transplanted organ, the less likely it ultimately will.

Still the possibility of rejection is one reason why it's also part of the procedure to counsel recipients and prepare them for life with a transplanted penis.

Van der Merwe admits he worried about how well his patient would cope psychologically after the operation was over. But there was no need for concern. "My joy was, with this guy, he immediately accepted it. He was so happy to have a functioning penis again."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))