If there's one defining characteristic of political discourse in our era, it's that the truth is swamped by myth. Made-up stories saturate social, and other, media — and real journalism is falsely targeted with chants of "fake news."

So it's the perfect moment to reflect on Ernesto "Che" Guevara, the veritable embodiment of the power of myth to eclipse reality. More than 20 years ago, Jon Lee Anderson set out to disentangle the revolutionary's real history from his legend. The result was the critically acclaimed biography Che: A Revolutionary Life. Now, in partnership with award-winning political cartoonist José Hernández, Anderson has adapted Che into a 421-page illustrated biography.

Anderson takes on a particularly unwieldy subject in Guevara. Even writers who criticize the Che myth are irresistibly drawn to focus on it — to point out that the most famous image of Guevara was shot by a fashion photographer, or that so-many-thousand people have visited his mausoleum in Cuba, the country he helped Fidel Castro take from the dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959. A fixation on Guevara's epic qualities is perhaps natural given his addiction to the guerilla life. Both as a middle-class Argentine medical student and as second-in-command to the triumphant Castro, Guevara turned his back on the prosaic realities of law and routine to live as a perpetual revolutionary. At various times, Guevara trained or fought in Guatemala, Mexico, Bolivia and the Congo. His personal ideology, too, emphasized the importance of spreading revolution around the world.

Guevara's many maxims reflect both his cruelty and his idealism. Sometimes both qualities make an appearance in ironic succession, as in Che's final quote in the book, from a letter he wrote to his family: "Remember that the revolution is the most important thing, and that each one of us, alone, is worth nothing. Above all, try to be able to always feel deeply any injustice committed against any person in any part of the world." For Guevara, these two approaches to the value of individual life were harmonious. It's Anderson's triumph that he enables the reader to understand how that could be the case.

It has to be said, though, that Anderson's attitude toward contemporary readers is a bit... cranky. He decided to adapt this book, he writes in the introduction, because he thought a graphic novel might help "explain Che to youngsters who, unlike those of us who lived through the sixties and seventies, can't imagine picking up a gun to fight for their ideals." But comics isn't simply a format that happens to appeal to attention-span-challenged "youngsters" lacking the stamina for real books. It's a medium all its own, with its own powers and limitations. Here, it places an indelible stamp on Guevara's tale — one that Anderson may not have intended.

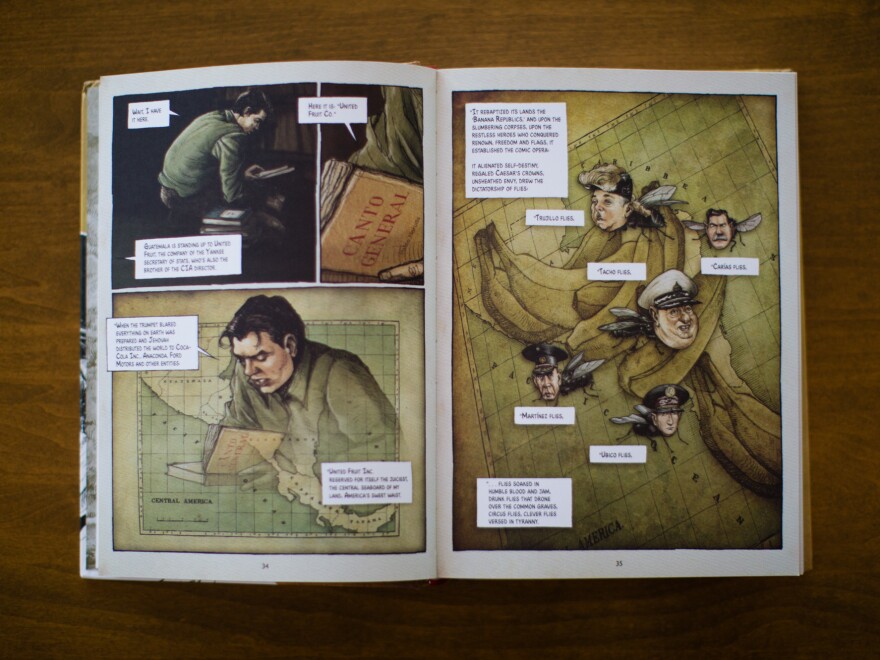

In fact, comics isn't really the ideal medium for a story aiming to puncture myths. Its signature tools, after all, are exaggeration and condensation: The artist makes a person memorable by boiling down and blowing up their features until they're identified irrevocably with one or two notable characteristics. Hernández and Anderson struggle continually to balance nuanced truth with cartoony distillation. Usually they succeed, and Anderson's well-balanced reportage is brought to life by Hernández' subtle, ever-changing faces. Hernández is a phenomenal draftsman with a cinematic eye. The mid-century time period is rendered in sepia hues perfect for a book of history, and many full-page compositions cry out to be framed. The sheer amount of artistic labor that's on view in these 421 pages is awe-inspiring in itself.

Still, the creators falter when they try to condense complex ideological questions into too few panels. The most drastic case is the book's treatment of the single most controversial episode in Che's life: his role, shortly after the revolutionaries took power in Cuba, in directing the executions of several hundred of Batista's functionaries. In the original biography, Anderson addresses a wealth of issues surrounding the executions. He discusses what evidence there was, and wasn't, against the prisoners; what specific offenses were held to justify execution; and how long the trials lasted. Here the whole episode takes up a mere three pages and lacks context.

Even with its problems, though, Che remains a remarkable accomplishment, one that belongs next to such works of graphical history as the March series and Shigeru Mizuki's Showa books. By foregrounding the tension between myth and truth, Che illuminates the present state of our politics as well as the past.

Etelka Lehoczky has written about books for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times and Salon.com. She tweets at @EtelkaL.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.