On Christmas Eve 1986, a South Africa prison commander responsible for watching over Nelson Mandela casually asked the world's most famous prisoner, "Mandela, would you like to see the city?"

Mandela was completely surprised, but agreed. The prison commander, Lt. Col. Gawie Marx, promptly put Mandela in his car for a leisurely drive around Cape Town, one of the world's most scenic cities.

They traveled the stunning cliff-side road overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. They meandered around the city for several hours, watching white South Africans go shopping, walk their dogs, or just enjoy the sun.

At one point, Marx pulled into a convenience store to buy cold drinks, leaving Mandela alone in the car for several minutes.

"For the first time in 22 years, I was out in the world and unguarded," Mandela wrote in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom. "I had a vision of opening the door, jumping out and running and running until I was out of sight. Something inside was urging me to do just that."

But he didn't. And Marx soon returned with two Coca-Colas.

Mandela's 27 years in prison were dominated by tremendous hardship. There were freezing winter nights, suffocating summer days, poor food and back-breaking labor. He slept on a thin mat on a stone floor for most of his time behind bars. For many years, his wife was allowed to visit only rarely and his children not at all.

But there were also moments of high drama along the way, including aborted escape plans. And in the final years, the white government began treating Mandela almost like an honored guest in preparation for his release in 1990.

Prison officials quietly smuggled him out for secret talks with two South African presidents. He met regularly with government ministers at their private homes, and they came to visit him when he was treated at a whites-only hospital near Cape Town.

In the last of the three prisons where he was held, Mandela lived in a secluded cottage with a backyard swimming pool. He had a personal cook, a white prison official who objected to Mandela's choice of cheap, semi-sweet wines and insisted on bringing more expensive, dry whites for the frequent family, friends and political colleagues who visited Mandela for lunch.

The Early Years

Of course, it wasn't that way in the beginning when Mandela was sentenced in 1964 to life for sabotage and placed on Robben Island off Cape Town.

In the early years, Mandela and other black prisoners had to battle just to be treated on par with other non-black prisoners. For years, they demanded that black prisoners, who were given one teaspoon of sugar daily, be allowed two, the allotment for Indian and mixed-race prisoners.

Victory was achieved when prisoners of all races were given 1 1/2 teaspoons a day.

Mandela and his prison colleagues assiduously cultivated good relations with many prison guards and gradually negotiated better conditions for themselves.

They worked daily in a limestone quarry on the island for years, and repeatedly asked for the practice to end. In 1977, the prisons system agreed and abolished manual labor for inmates.

But the downside, Mandela noted, was that he began to put on weight without his daily work regimen. In response, the prison staff agreed to build a tennis court in the prison courtyard. Mandela, pushing 50 at this point, was an avid if not particularly skilled player.

"My forehand was relatively strong, my backhand regrettably weak," Mandela said in assessing his game.

During a 1979 match, he hurt his heel and had to be taken by boat to a Cape Town hospital for treatment. During this period, when prison conditions were still extremely rough, the only way off the island was for specialized medical treatment.

Several years earlier, one of Mandela's prison colleagues was sent to a dentist in Cape Town. While in the waiting room on the second floor, he noticed a window that could facilitate an escape.

When he returned to Robben Island, he shared this with Mandela and urged him to request dental treatment. A few months later, Mandela and two other prison colleagues found themselves in the same waiting room, briefly unattended and with their leg shackles removed. They looked out the window as they entertained the notion of making a run for it.

But they saw that the surrounding streets of central Cape Town were suspiciously empty for the middle of a working day. They suspected they were being set up by the white authorities, and that they might be shot if they tried to escape. So they dutifully proceeded to their checkups — and were promptly shipped back to Robben Island.

Move To Another Prison

Mandela was moved off the island in 1982 to Pollsmoor Prison in suburban Cape Town, and conditions were, in relative terms, much better. He was allowed to have "contact visits" with his family beginning in 1984.

His then-wife, Winnie, had been allowed limited visits to Robben Island, but the couple had to communicate over scratchy microphones from opposite sides of a glass partition. Now they could meet and embrace in a visitor's room.

"It had been 21 years since I had even touched my wife's hands," Mandela said.

In this new environment, family visits were more frequent, and a limited number of high-profile foreign dignitaries were now allowed to see Mandela.

In 1986, the South African government began making its first serious overtures, and Mandela was secretly driven from the prison to the home of Kobie Coetsee, the justice minister, who would meet often with Mandela in the years that followed.

At the same time, the prison officials began taking him for semi-regular excursions around Cape Town to show Mandela what the modern South Africa looked like, and to help prepare him for a possible release.

The outings became so routine that junior prison officials did the driving, taking Mandela for walks on the beach and tea in cafes. One young officer took Mandela to his apartment and introduced him to his wife and kids.

"At such places I often tried to see if people recognized me, but no one ever did," Mandela wrote.

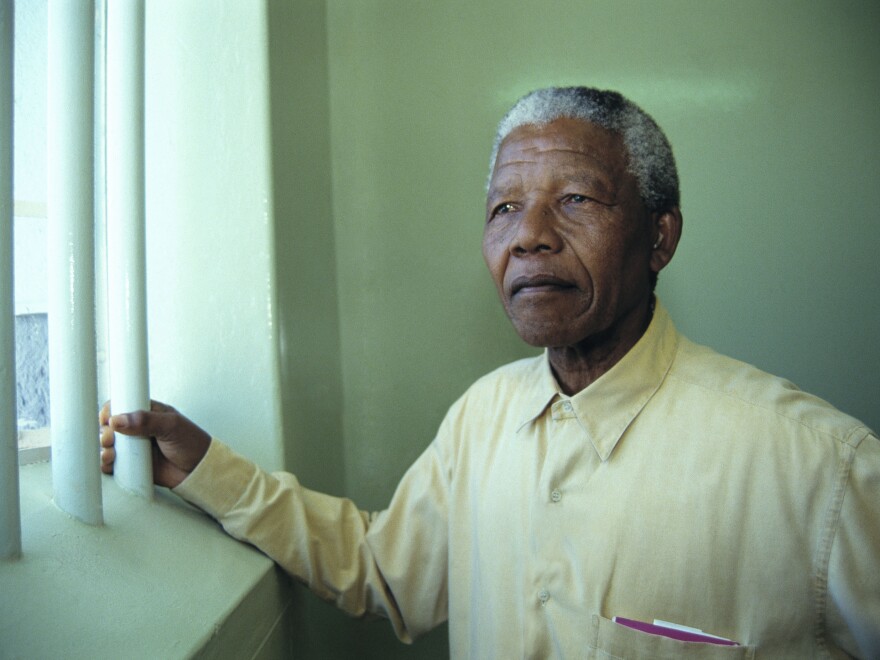

How is that possible? The white government did not allow photos of Mandela to be published while he was in prison, and therefore the public had no idea of what the elderly Mandela looked like.

A Serious Illness

Mandela came down with tuberculosis in 1988 and spent six weeks recuperating at a hospital and the whites-only Constantiaberg Clinic outside Cape Town.

The damp conditions at Pollsmoor Prison were believed to have contributed to his illness, so upon his release from the hospital Mandela was moved to Victor Verster Prison, also outside Cape Town, where he had a secluded cottage with the pool. When he arrived, he was greeted by Coetsee, the justice minister, bearing a case of wine.

"The cottage did in fact give me the illusion of freedom," Mandela wrote. "I could go to sleep and wake up as I pleased, swim whenever I wanted, eat when I was hungry."

Mandela and his cook, Warrant Officer Jack Swart, became good friends, though they occasionally quarreled when it came to doing the dishes. After a particularly savory meal, Mandela would volunteer to do them. Swart would always refuse, only to relent when Mandela kept insisting.

"It was altogether pleasant, but I never forgot that it was a gilded cage," Mandela said of his final prison.

Meeting The President

After three years of increasingly frequent meetings with government officials, Mandela was offered a secret meeting with President P.W. Botha on July 5, 1989.

Prison officials realized they couldn't send Mandela to the talks in his prison garb, so they called in a tailor to fashion a bespoke suit. But when the big day arrived, Mandela, who hadn't put on a tie in decades, was unable to knot it properly.

The prison commander immediately took it upon himself to remove Mandela's tie, stand behind him and tie a perfect double Windsor knot.

When Mandela arrived at the president's office, one of the country's top security officials, Dr. Niel Barnard, noticed that Mandela's new shoes were not tied, a skill that had also lapsed after so many years of wearing slip-on prison shoes. Barnard promptly took a knee and tied them for the prisoner.

A few moments later, his wardrobe smartly in place, Mandela entered the president's office looking like, well, a future president.

Seven months later, Mandela would be a free man. And a few years after that, the president's office would indeed belong to Mandela.

Greg Myre, the international editor for NPR.org, covered South Africa from 1987 to 1993 for The Associated Press.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))