Imagine setting out to write a definitive book on someone you think is a visionary. Then your story's hero transforms into a villain in much of the public's opinion before you have finished your tome.

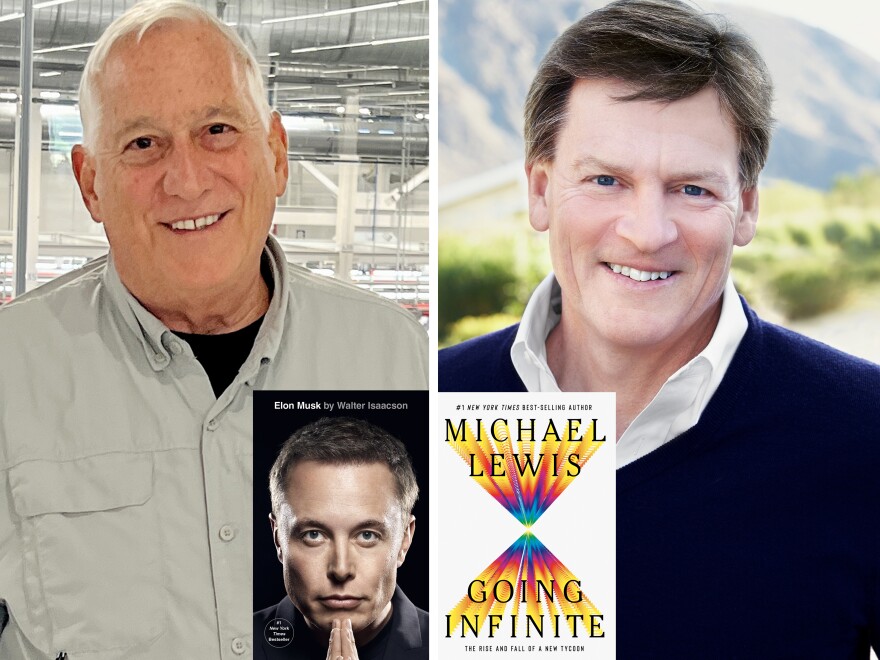

That just happened to two of the most prominent chroniclers of American life: Michael Lewis, who also wrote bestsellers Moneyball and The Big Short, and Walter Isaacson, biographer of Steve Jobs and Leonardo da Vinci.

Lewis spent two years with FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried, once considered a golden boy of cryptocurrency, for Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon. It was released this month, on the first day of Bankman-Fried's fraud trial.

Isaacson spent an equal amount of time — two years — with another tycoon, Elon Musk, as the Tesla and SpaceX CEO was turning his sights to Twitter. Musk has since bought the social media platform, fired most of its employees, used it to amplify conspiracy theories and renamed it X. Isaacson's book came out in September.

These highlights were adapted from the full interview.

On their characters' seeming indifference

Walter Isaacson: It was a bit of a surprise because I talked to [Musk] by phone and we talked about an hour and a half and I said, "I don't want to do a book based on five or 10 or 15 interviews. I don't want to do a conventional book like that. I want to be by your side for two years. And every meeting I want to be in — nothing excluded." And he went, "Oh, OK." And then I said, "But here's the other part of the deal: I don't want you to have any control over it, and I'm not going to let you read it before it's published." And he went, "Oh, OK." And I was kind of stunned.

Michael Lewis: It didn't take anything [to gain access to Bankman-Fried]. I was introduced to him by a third party who wanted me to get to know him so I could evaluate him for a business deal. So I didn't even know who he was when I met him, and I spent a couple of hours with him. At the end of it, the sort of stuff that was coming out of his mouth was so interesting to me that I just said, "Look, I don't know what I'm going to do or where you're going to go or how this is going to end. But can I just watch?" ... He was so indifferent to it. He never asked me what I was up to. He certainly didn't want to see the book or ask to see the book. He kind of left me alone. And it's odd that people do this — that Elon Musk and Sam Bankman-Fried do this. But I think in some ways their characters rhyme a bit.

On maintaining a sense of critical distance from their subjects

Isaacson: I had to keep my head around very contradictory things, which is the awesome ability to, say, connect solar roofs to power walls and the engineering that makes it so, while also holding in the fact that [Musk's] lack of emotional receptors and his dark streak that comes from "demon mode," as [former partner] Grimes calls it, from childhood allow him to promote conspiracy theories when he takes over Twitter. If you were able to cleave off both his use of Twitter and his buying of Twitter — and that's actually where I was when I first started this book — you'd have a book about a pretty darn interesting engineer. Now you've got a book in which you've got to keep two or more than two different types of people in mind.

Lewis: I've never had so little trouble keeping a feeling of distance from a character [Bankman-Fried] because the character kept a feeling of distance from me. I've never had anybody feel so little for me, so I didn't have any trouble feeling so little for him. ... I regarded him right from the beginning as walking social satire and loved his company. I still love his company. I wish I could be in his jail cell with him for a night. ... What's going on around him and his view of the world is interesting.

On Bankman-Fried's fraud trial going on now

Lewis: It might create another book, the trial. I framed this as the rise and fall of this person's peculiar ambitions to make as much money as possible to address an existential risk to humanity. And that dream ended, and that was the end of that story.

But there is this other story that if it gets much richer, it's very tempting to write. And it's a story of Sam Bankman-Fried colliding with yet another system and stress-testing it: the criminal justice system. There's a part of me that really wishes I wasn't here but was in the courtroom. And I may get there and do something long with it. I mean, the shocking outcome right now would be if he's acquitted.

On writing about an antihero in this particular moment

Isaacson: I don't know that it's harder to write about an antihero. I think it is harder in this day and age to write about somebody who's complex. ... In this day and age, we have snap judgments. People are heroes or villains. And when you have a character, as Shakespeare teaches us, that is "molded out of faults," it's harder to write about them because people want you to be outraged, one side or the other.

On criticism that Isaacson didn't come down hard enough on Musk's failures

Lewis: I'm sorry. I'm going to defend Walter because he shouldn't have to defend himself. ... I've read the book. And the critics themselves are often relying on what Walter has supplied to attack the book and attack the character. Like, they wouldn't know what they know without Walter's book. All they're supplying is moral outrage. Who wants that? That's not the writer's purpose here. And it's not a tool for enlightening anybody.

Isaacson: Well, I do think that I try to tell a story, and I love the people who say, "OK, you should have come down harder and made judgment." But the judgments are there in the stories. And I guess my goal is to tell the story as straight as I could and as honestly as I could and let the reader have some control over the reader's own moral judgments.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.