Children on tattered rollerblades weave through crowds of people on the streets of South Africa's Masiphumelele township. Outside a cluster of colorfully painted shacks, young men sit hunched over a game of dominoes, and a woman has her hair braided by friends on a sidewalk. There is not one face mask or bottle of hand sanitizer in sight. Nothing, in fact, that would give away that the country is entering its fourth week of a nationwidecoronavirus lockdown.

Walk just a few miles over to neighboring suburbs, however, and you'll find yourself in a ghost town, where birdsong echoes through empty streets.

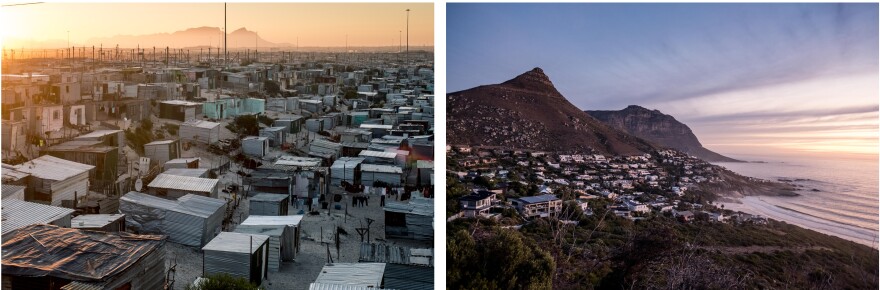

Twenty-six years after the end of apartheid, South Africa is, according to the World Bank's calculations, the most unequal country on earth. In Cape Town, the second-largest city, well-to-do suburbs sit side by side with sprawling, corrugated-zinc townships. Driving from one neighborhood to another can be a jarring experience at the best of times. But since the country went into lockdown in late March, the city's social divisions have been brought into sharper focus than ever.

Khayelitsha is the largest of Cape Town's densely populated townships, with a population in the hundreds of thousands. Residents say it has been virtually impossible to act on the government's health warnings.

"The health workers say we must wash our hands," says Zukwisa Qezo, a 47-year-old mother of two who works for a local charity. "But with what?! The city must bring us soap."

As she talks, people walk up and down the sandy alleyway outside the cramped home she shares with her family.

"They tell us we have to stay at home, but we're using communal toilets and communal taps, and the shops are far from here," says Qezo, whose organization is trying to raise awareness about infection prevention. "We'll do our best. But the virus will spread quickly."

Nearby, a group of about a dozen janitors mill around on a street corner. Their team is responsible for cleaning more than 200 toilets in the area — each used by roughly 30 or 40 people a day. But they say they have no cleaning products.

"We don't have any chemicals or sanitizer," says 36-year-old Noxolo (he only gave his first name), who lives in a one-room shack with five other people. "We don't even have face masks. All we have is these short gloves."

A few miles away in another part of the township, a queue more than 300 feet long stretches out of a supermarket and trails around the perimeter of an empty parking lot. Fridges are a rare luxury, and few can afford to buy in bulk, so trips to the shops are frequent. And with stores limiting the number of shoppers inside, huge backups are created.

"Sometimes it's an hour and half, sometimes two hours, sometimes longer," says one man waiting in line. Asked if he worries about catching the virus in this crowded environment, he replies that he is, but there isn't much he can do about it.

"At least the queue is outside," he says. "Maybe the wind will blow the disease away."

South Africa has so far registered some 3,300 cases of COVID-19. Yet in the townships, fear of the virus is outstripped by the fear of running out of money, as the lockdown has brought the economy to a grinding halt. Few Khayelitsha residents had much in the way of savings when the virus struck, and many are increasingly worried about how they'll continue to feed their families if the lockdown continues. Last week, riots erupted in the township of Mitchells Plain after rumors of a food distribution turned out to be false, and a string of shops and food trucks have been looted.

Asked what she thinks might happen if the lockdown restrictions are extended, Qezo's reply is stark: "People will die. We'll die because of hunger."

Many of those who help keep the city's hospitals and food supply functioning live in the townships. They're exempt from the government's stay-at-home order, but few have cars. To reach their workplaces, they must risk contracting the virus on one of the few buses still running.

"If I must get sick, what can I do?" says Anna Simpson, who works in a hospital kitchen in the city center, as she waited for a bus to take her back home to a community known as Lost City. "I'm lucky I still have a job."

Along the coast in the suburbs of Muizenberg, Kalk Bay and Fish Hoek, lockdown has a very different vibe. The streets are virtually empty of traffic. An eerie quiet hangs in air, and the noise of the wind and the waves seems amplified. On one usually busy road, flocks of guinea fowl have taken to wandering along the tarmac, no longer fearful of traffic.

The lockdown has affected everyone in the city in some form or another. But here in the suburbs, the problems are less urgent.It's comparatively easy for people to maintain social distance when they own a vehicle and can stock up fridges and freezers with food to limit the frequency of trips outside. The loss of work is a blow to many, but nobody here is talking about running out of food.

"We inhabit two worlds here," says Mark Gevisser, a prominent South African journalist who has written about the "incredible dissonance" between the experience of lockdown in the suburbs compared to the townships. "It just feels like that's in such stark relief at the moment, when I think about how I'm able to take shelter and even the pleasure I can get in my home."

Gevisser lives in an open-plan two-story home in Kalk Bay, with a wide balcony that looks onto the broad sweep of False Bay and the Kogelberg mountains beyond. He has spent the last seven years working on his latest book, about the LGBT rights movement, which will now be released into a world preoccupied with other matters. It's a painful pill to swallow, but he is acutely aware that his own worries do not compare to those of many other South Africans.

Since the lockdown began nearly three weeks ago, Gevisser has left his home only to buy food and for a stint as a volunteer driver for a local hospital, delivering medicines to residents of a nearby township.

Across the suburbs, as elsewhere in the world, many are using the lockdown as an opportunity to get around to things they haven't previously had time for. Gevisser is taking online yoga classes. Others tend to their gardens, try new hobbies, binge-watch Netflix series and exercise to online workout videos in their front yards.

Throughout South African history, the relationship between epidemics and social division has been a complex one. In the current outbreak, the city's geography of separation may have slowed the spread of the disease from the first wave of cases — brought into the country by comparatively wealthy international travelers — into the townships. Yet if and when the coronavirus does start to take hold, conditions in the townships will worsen its spread. Consequently, South African scientists predict the country's coronavirus trajectory will follow an unusual double curve, mirroring the country's divided population — one spike for the wealthy and a second for everyone else.

According to Howard Phillips, a leading historian of epidemics in South Africa, outbreaks of disease can not only highlight the fault lines in society, they can also play a role in creating those fissures. In a phone interview, Phillips points out that the first forced expulsions of black Africans from Cape Town and Johannesburg came in response to plagues in the early 20th century, when black neighborhoods in the cities were considered health risks by the white elite.

"The origins of Soweto go directly back to the pneumonic plague of 1904," he explains, referring to the massive township on the edge of Johannesburg. "After the epidemic, the Indians were allowed to come back, but the Africans weren't."

And when the Spanish flu hit the country in 1918, some of the satellite settlements created during the earlier outbreaks were replaced by others even farther from the urban centers.

Phillips, whose research explores how epidemics provide opportunities or triggers for governments to take actions not possible in ordinary times, sees a similar phenomenon unfolding in the current outbreak. Refugees have been forcibly removed from buildings in the city center where they'd been squatting. The government has said it will use phone data to trace coronavirus contacts, though it insists this practice will not outlive the epidemic. It has evicted families from long-standing informal settlements on city-owned land, prompting an outcry from families who now find themselves without shelter in the midst of a pandemic.

And it has moved more than a thousand of the city's homeless into fenced-in enclosures patrolled by security guards in the south of the city, a move the government describes as a measure to control the spread of the virus.

Among them is George Baraina Dos Santos, who had been living on the streets of the upscale neighborhood of Green Point before being brought by the government to a camp set up on empty sports fields in the suburb of Strandfontein in the south of Cape Town.

"Just look how we're sleeping," says Dos Santos, indicating a large white tent behind him where men and women lie on thin mats, packed side by side on the floor. "And they only gave us one blanket. Most of us had more than that on the streets."

Dos Santos says he feels trapped. He does not see how hundreds of people in a cramped space will be able to practice social distance. And it concerns him that none of the people he arrived with were tested for the coronavirus before being admitted to the camp.

The charity Doctors Without Borders has already called for the camps to be phased out.

Since Dos Santos arrived, there have been protests, a minor riot and an alleged rape. One morning, he woke up to find the man next to him had died in the night. Fights are an everyday occurrence, he says.

As if on cue, shouts erupt from the direction of the toilet block behind the sleeping tent as a brawl breaks out.

"They brought us here and told us this was a safe place," says Dos Santos. "But they don't seem to have a plan."

City authorities point out that the camp was built in a hurry and say they are addressing the problem of overcrowding by erecting more tents. It is, they say, a work in progress.

On Monday, the president said that the lockdown had exposed "a very sad fault line in our society that reveals how grinding poverty, inequality and unemployment is tearing the fabric of our communities apart."

The current lockdown period is due to end on May 1, leaving the government with an impossible decision: to lift the lockdown at the risk of exacerbating the spread of COVID-19 or to extend it again, at a time when millions of the poorest South Africans are becoming increasingly desperate.

Tommy Trenchard is an independent photojournalist based in Cape Town, South Africa. He has previously contributed photos and stories to NPR on the Mozambique cyclone of 2019, the Ebola outbreak and Indonesian death rituals.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.