Rising drug prices are one of the biggest challenges in health care in the United States. More people are using prescription drugs on a regular basis, and the costs of specialty drugs are rising faster than inflation.

President Donald Trump has promised over and over again to drive down drug prices.

Just last week on Twitter he wrote: "I am working on a new system where there will be competition in the Drug Industry. Pricing for the American people will come way down!"

But Trump already has a weapon he could deploy to cut the prices of at least some expensive medications.

That weapon is called "march-in rights."

Here's how it works. When the federal government — through an agency like the National Institutes of Health — pays for medical research that leads to an invention that can be patented, federal law gives the government a license to use that intellectual property.

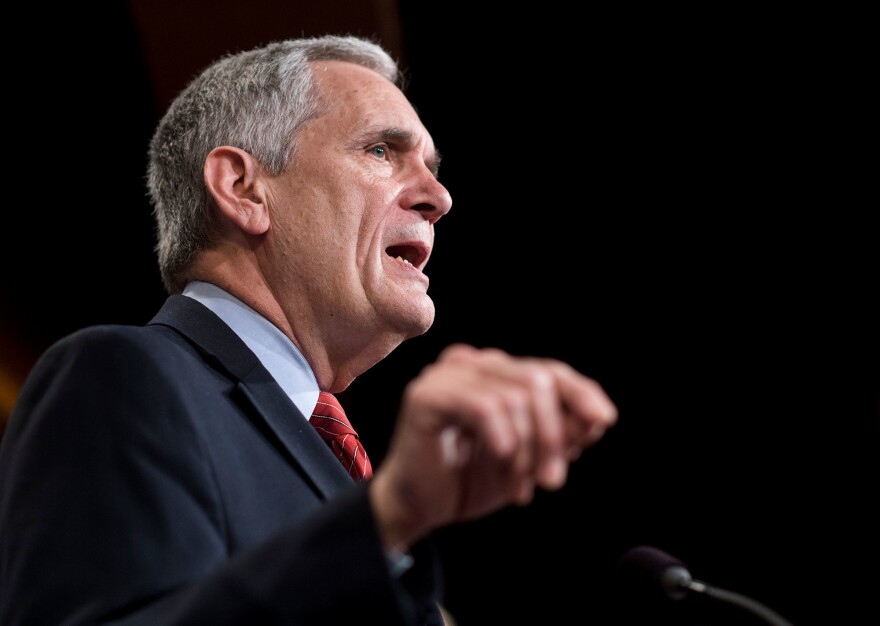

Rep. Lloyd Doggett, a Texas Democrat, wants the U.S. to exercise those rights to force down drug prices.

"I believe that when taxpayers finance research that produces a pharmaceutical, they have an interest in being able to afford that pharmaceutical, and that's not happening now," Doggett told Shots.

What is happening is that the government pays for the research and the doctors and companies market the medications. The government retains a license to the intellectual property as a check, to ensure that the medicines are available to the public on "reasonable terms."

But, Doggett said, the government has never used its march-in authority.

"Millions of dollars go out and federal research dollars; pharmaceuticals result, and then they get priced at such outrageous levels," Doggett said. "They're so high that some people cannot afford them."

Last year Doggett, along with 50 other members of Congress, backed a request by the group Knowledge Ecology International for NIH to use its march-in authority to lower the price of Xtandi , a prostate cancer drug.

At the time the medication was sold by a Japanese company for about $88 a pill, according to KEI, a nonprofit organization that advocates for social justice. Last April, KEI said, a Canadian drug company offered to sell a generic version of Xtandi to the government for just $3 per pill.

NIH declined to use its license or take that offer.

Doggett and KEI appealed to former Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell, who declined to overrule the NIH.

Doggett then asked HHS to simply hold hearings, and lay out guidelines for when it might consider exercising march-in rights in response to price gouging. Again, the agency refused.

Burwell said march-in authority is only allowed if certain criteria are met, "such as alleviating health or safety needs, or when effective steps are not being taken to achieve practical application of the inventions."

She said the agency considered, in 2004, whether high prices meet those criteria and determined they do not. In that case the agency was looking at expensive drugs to treat HIV and AIDS.

"The attitude there seems to be, 'We're not in the pricing business, we're only in the research business and we're not too interested in getting into the pricing business,' " Doggett said.

But Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School who studies intellectual property law and drug development, thinks the agency should be interested.

"When you think of the phrase 'reasonable terms' — reasonable terms inherently means, I think, the price that a drug is available for," he told Shots.

If the Trump administration decided to go that route, Kesselheim said, it could use its license to contract with a generic pharmaceutical manufacturer to make the drugs at a lower price. Or it could, potentially, take that license and buy the medications from a foreign drug maker.

A radical move like that could have an effect on drug prices across the board, said Sara Fisher Ellison, an economist at MIT.

"Definitely an unusual action like that could have spillover effects on the drug prices of other companies," she said, "because obviously they might see themselves as the next potential target, and might want to make themselves a less attractive target by lowering their prices."

But those lower prices could also make drug companies less eager to invest lots of money in new medications.

That's the trade-off the government has always had to wrestle with. But it's one Trump could very well decide is worthwhile.

"Perhaps we as a country would rather have lower drug prices and a little less innovation," Ellison said.

Doggett hopes Trump might just take that deal.

"This is something where President Trump, if he wants to fulfill a campaign promise, can take action that the last administration refused to take in order to protect consumers," Doggett said.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAwMTM1NDgzMDEyMzg2MDcwMzJjODJiYQ004))