"This is a little walk I take every morning, just to spend time with God."

Jack Hall is meandering along a path around the backyard of a modest home on the Northeast Side of San Antonio.

"The wind chimes, when the wind is blowing, these things are beautiful," Hall said, before giving them a tap to demonstrate. He gestured to the right, where there is a prayer wall holding several candles, and then wandered to the other side of the yard, where there is a thick, knotty old oak.

"This is just one strong tree, here,” Hall said. “This tree has stood the test of time, and it'll be here long after we're gone."

Hall has prostate cancer that has spread to his lymph nodes. He’s dying, and is one of the growing number of Americans who are dying with no family nearby.

"They’re spread out all over the place," Hall said. "They’re in Raleigh, North Carolina, down in Rockport. My ex-wife and my daughter are up in Bentonville, Arkansas, and I’ve got some friends that actually live in this neighborhood, but I couldn’t depend on them. I can’t force myself on them."

As the largest generation of the last century ages into retirement and some of the oldest baby boomers reach the end of their lives, it's becoming clear that a crisis is brewing in end-of-life care. More than a few are like Hall, and lack what social scientists call social capital, which is essentially a support system nearby.

According to research completed for the U.S. Senate Joint Economic Committee's Social Capital Project, 25 years ago, 68% of retirement-age adults lived within 10 miles of their children. By 2014, that figure fell to 55%. In that same time period, retirement-age adults with any relative in their neighborhood fell by 12%, and those with a good friend nearby fell by 10%.

So, what happens to these aging adults without support systems and often with no place to go when they get a terminal prognosis?

In San Antonio, some of them go to a place called Abode Contemplative Care for the Dying.

Martha Jo Atkins is Abode's Executive Director.

"Abode is a non-profit, end-of-life home where we care for people who don’t have a place to live or don’t have someone to care for them, and typically these folks are in the last three-ish months of life," Atkins said.

It’s a non-medical home, meaning staffed by a managing director, who is a registered nurse, several staffers called End-of-Life Navigators, who help care for the dying, and volunteers.

"There’s no nurse, no doctor, no IVs… this is really genuinely, truly a home,” Atkins said. “Anybody can go in the kitchen and cook. We don’t have rules. People don’t have to eat at a certain time or be anywhere. We don’t wake everybody up and roll them out into the day room. That’s not what happens here."

People are referred to Abode by their Hospice social workers. There are three private rooms there. Hall has one that he often shares with the household dog, Sadie. He shows off his private space with pride and something like awe.

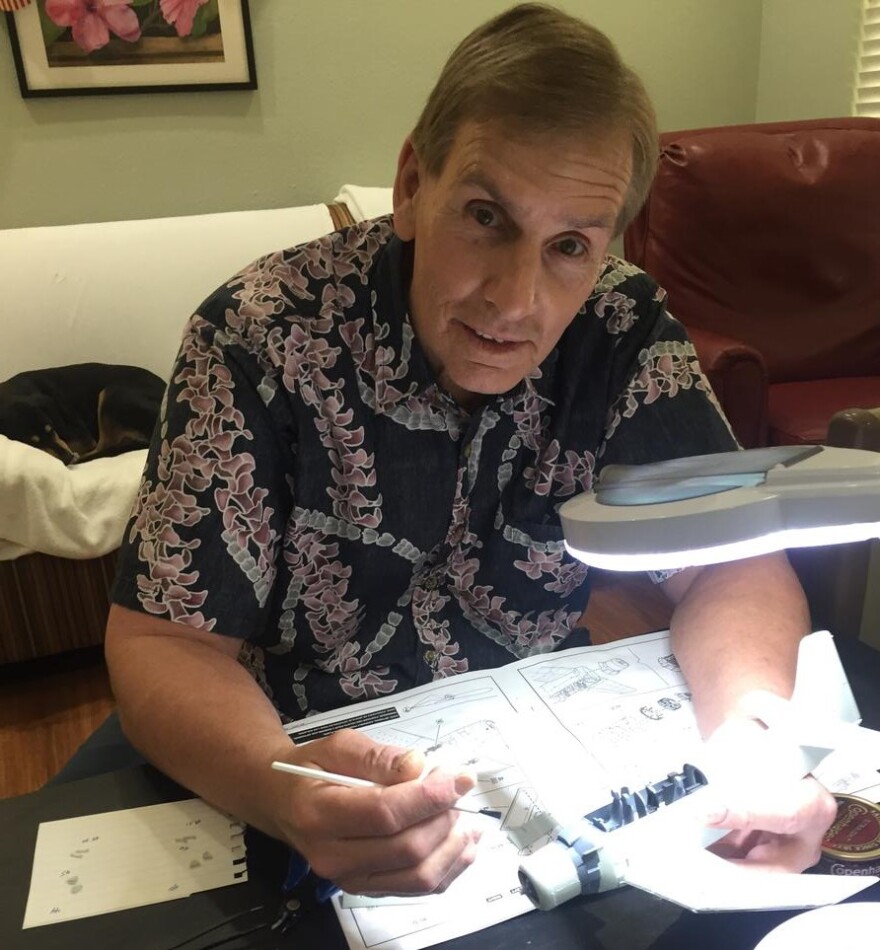

"This is my old work table where I build my planes and do my bible studies,” Hall said. “My Chrome book where I do a lot of writing. My classical music. Sadie’s bed, she comes in and gets cold at night."

Hall is dying, but in many ways he feels like he's finally living. Atkins said that's what they're trying to do there. She spoke directly to Hall when describing how she sees their role in what she calls his “journey.”

"When he dies, we’re going to be sad, and we’re going to miss you,” Atkins said. “I think it’s important to say that out loud, because you’re important to us and you’re our family now."

This is the only non-medical end-of-life home in San Antonio. It is part of the Omega Home Network, which includes 26 other community homes for dying people across the country.

"They need more of them because some people aren’t financially able to have a place to pass away,” Hall said. “Unless you want to go to the San Antonio bridge and die under one of those. I don’t plan on doing that."

Atkins said they expect the need for places like Abode to surge over the next decade.

"People assume they’re going to be able to die in the hospital, and sometimes that’s true,” Atkins said, “And there are people who die under the bridges here.”

But Atkins added, “And three people at any given time in San Antonio have a place to lay their head and be surrounded by love and die with dignity."

According to the SCP, by 2060, more than 21 million Americans over the age of 50 will be without a living partner or child.

Bonnie Petrie can be reached at Bonnie@TPR.org and on Twitter at @kbonniepetrie.