Thank you, Mexico

I've seen a fair number of Thanksgivings pass in my day, almost all of them spent in Texas, with friends and family. It's by far my favorite holiday since it is truly about being thankful for family, friends, and good food. I don't take it for granted.

I spent six Thanksgivings in Mexico, an experience which, if anything, has enhanced my appreciation of this American Holiday. In 1981, I took a job playing in the Orquesta Filarmonica de la Ciudad de Mexico (Mexico City Philharmonic). It was an opportunity not to be squandered, and a chance for me and my wife, both of us French horn players, to work together in the same orchestra. And what an orchestra it was! This was a huge promotion for both of us and also the beginning of six years of a great adventure within a different culture.

The Philharmonic was an interesting cultural mix, made up of more or less equal parts Mexican, American, and European musicians. I soon made friends within the orchestra. The Americans stuck together but also intermingled with the Mexicans, Poles, Russians, Estonians, and even a Canadian timpanist.

My wife Margaret and I were still getting our bearings when Thanksgiving rolled around. Of course, it's not a Mexican holiday, so it was a work day. However, there was already a tradition in the Philharmonic of carving out a time and place for a Thanksgiving feast. The meal was a full blown pot luck, including as many of the traditional American dishes as were possible. Back then, turkeys were not readily available in the markets. You had to plan ahead, reserving a turkey from one of the larger supermarkets.

Friends gathered, a cross-cultural affair as the Americans shared “their” holiday with others in the orchestra. After all, this was, and still is, a holiday of thanksgiving. We all had newly made friendships to celebrate and then there was the job we all shared. We all knew we were extremely fortunate to be making music together in a fine and well compensated orchestra. Of course, being paid a salary on the level of the Chicago Symphony couldn't last forever. A series of currency devaluations dosed us all with a painful fiscal reality.

Salary became a roller coaster, but the orchestra continued to play at a very high level. Such things sustain musicians. Another Thanksgiving came, and we again gave thanks. In fact, there was plenty to be thankful for each of the years I lived and worked in Mexico. It all was made even better by the friendly, the Mexicans might say amable, Mexican people. Most of us felt truly welcome in our host country.

Thanks to a generous nation

I had known of the Polish violinist Henryk Szeryng before I moved to Mexico. He was an international star and I had opportunity to not only hear him in recital (he was one of Sol Hurok's roster of artists) but also to play with him when I was in the San Antonio Symphony and Maestro Szeryng would come as a featured soloist with the orchestra. He was deeply committed to his music-making, but just as much devoted to his role as a teacher. I recall that he would wade into the orchestra, showing the players how he wanted the bowing and phrasing. We all admired him.

What I didn't know was how revered he was in Mexico. That reverence was two way. During the Second World War, Szeryng found himself a man in exile as the Nazi's overran Poland and so much of the rest of Europe. He found a temporary base in England, where he helped form a Polish government in exile. Szeryng's next big challenge was to find home for the thousands of Poles who were fleeing ahead of the destruction in their country.

Poland's exile government sought help throughout the free world. They were turned down by the United States, unwilling or unable to bear an influx of Polish refugees. In 1941, Szeryng accompanied General Wladyslaw Sikorski, the Premier of the Polish government in exile, to Mexico in search of a home for 4000 Polish refugees. The positive reception that the delegation received from the Mexican government, and Mexico's willingness to allow the refugees to shelter in Mexico, so moved Szeryng that he decided to become a naturalized Mexican citizen. In 1945, Szeryng accepted an offer made to him in 1943 to head the string department of the Natonal University of Mexico.

For the next 43 years Henryk Szeryng kept a home in Mexico in addition to his home in London. He continued to bestow upon Mexico his eternal thanksgiving for the generosity the country showed displaced Polish refugees in their time of need. I had the opportunity to appreciate the skill of numerous Mexican string players who had been taught by Szeryng, including violinist Manuel Suarez. I remember performing in Mexico City and Toluca with Szeryng who came as soloist with the Orquesta Sinfonica del Estado de Mexico, conducted by Manuel Suarez. There was always a sense of thanksgiving which one felt in the presence of Maestro Henryk Szeryng.

Thanks to the Latin Grammys

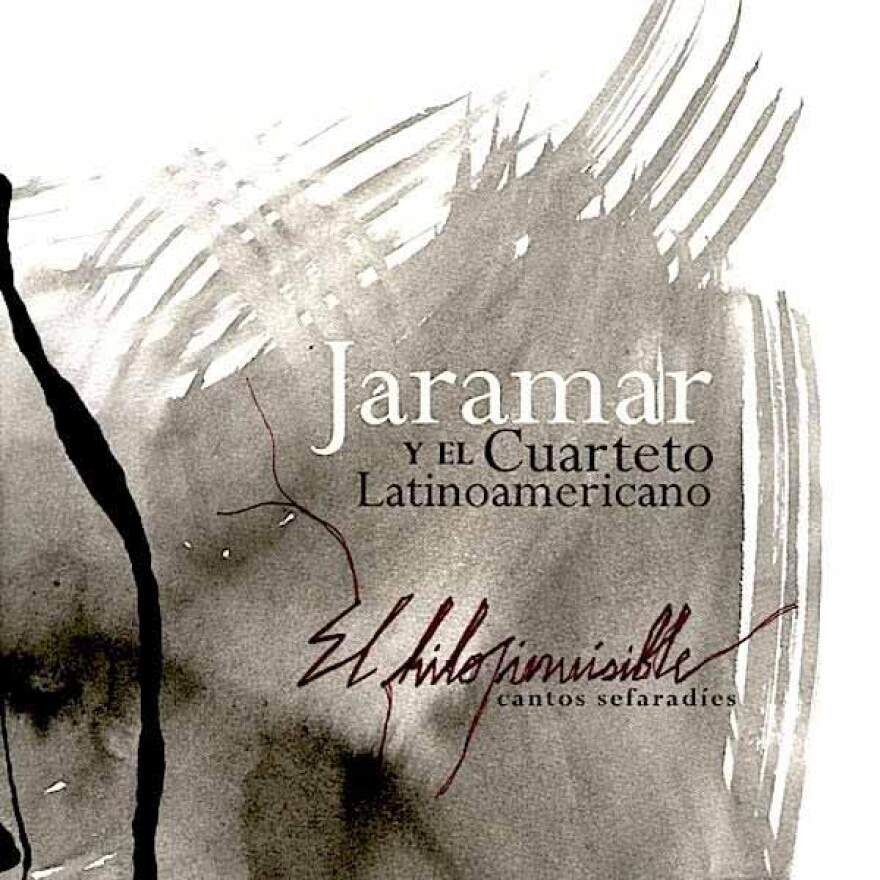

The Cuarteto Latinoamericano has much to be thankful for in 2016 for they recently received their second Latin Grammy, dominating the Best Classical Album category with their collaboration with the singer Jaramar Soto. The album, a collection of Sephardic songs, is called “El Hilo Invisible (The Invisible Thread).”

With the issuance of the Alhambra Decree in 1492 which ordered all practicing Jews to leave the Kingdoms of Castille and Aragon, many were left with nowhere to turn. The choice was between renouncing their Jewish faith and embracing Catholicism, or fleeing Spain and Portugal. The beginning of European exploration of the newly discovered Americas opened up one other avenue, but one which was very risky. Nevertheless, the desperation of the situation led some to enlist as sailors and laborers on ships sailing to the New World. It is even believed that some of the crews aboard the ships of the explorer Christopher Columbus included Jews who were fleeing the Iberian Peninsula.

Those who chose this solution left the Old World with little more than the clothing on their backs plus whatever memories they could store in their minds. Among the latter possessions were traditions and music.

It is the music of the Sephardic Jews which has been recently explored in a compact disc from the Cuarteto Latinoamericano and the singer Jaramar Soto. This is music from centuries ago which has been passed on from father to son, mother to daughter, an oral tradition which has since been preserved in contemporary musical notation. I have at times wondered if any musical manuscript might have physically traveled with the Jews who crossed the treacherous seas in 1492 and later, but it seems highly unlikely. The risk would have been too great, especially considering the danger of fleeing Spain only to arrive in newly discovered territories which quickly became part of a Spanish Empire. The Jews were no more welcome in New Spain than in Old Spain. The pain of having to live and practice one's faith in secret must have been severe.

A recent interview with Saul Bitran, one of the members of the Cuarteto Latinoamericano, sheds some light on the quartet's project which resulted in the album “El Hilo Invisible,” work which was recently recognized with a Latin Grammy as Best Classical Album.

About 5 weeks ago I phoned my friend Saul Bitran, a member of the Cuarteto Latinoamericano and an old colleague of mine – the Cuarteto and I worked together for several years in Eduardo Mata's ensemble Solistas de Mexico. I like to check in with Saul now and then to catch up on the Latin American Quartet's activities. They have been very active concert presenters since the quartet formed in 1982. I try without success to keep up with their recording activities but they always seem several steps ahead of me. Their discography must surely be at least a mile, maybe a mile and a half, long.

J.B. “How many recordings have you made?”

S.B. “Well, if you lost track, I also lost track with what we did. I haven't counted them recently, probably within 60 or 70, but I may be wrong.”

J.B. “Saul, tell me about the new recording, El Hilo Invisible.”

S.B. “Yes. This is a recording that we did, if I'm not mistaken, in March or February of this year and it consists of Sephardic songs arranged for voice and string quartet and the singer is a Mexican singer called Jaramar, a woman who specializes in folk music but she has also been very active singing Sephardic songs. She reached out to us in part knowing that the three Bitran brothers, we have Sephardic heritage and we grew up listening to these songs. My grandmother used to sing them all the time to me. So, she found some funds from the Mexico national funds for culture to commission arrangements and they came out beautifully and we recorded them and yes, we just got a Latin Grammy nomination for this album. We are very excited.”

J.B. “Is the title a reference to the difficult compromises the Sephardic Jews had to make in their transit as hidden, or invisible, refugees coming to the New World, or is it more complicated still?”

S.B. “Well, the title is very poetic and it gives free range for a lot of images, one of them certainly what you mention, the other one is this thread that has not been broken from 1492 when Sephardic Jews were expelled from Spain until today these songs have survived. Their language is endangered but it is still surviving. In Israel there are still newspapers in Ladino. Let me tell you a story. My grandmother used to tell me about a friend she had who came, as her, [from the Old World], and this friend of her still had the key to their house in Toledo from the 15th century that had been passed from generation to generation. So yes, it's invisible but it's a very powerful thread that unites each generation of Sephardic Jews.”

J.B. “'El Hilo Invisible' is nominated for a Latin Grammy. This isn't new territory for the Latin American Quartet. I think you've already won several, haven't you?”

S.B. “We have won only one Grammy. This is our sixth nomination but we won actually only one Latin Grammy in 2012. So I would hope this is going to be the second.”

J.B. “Thanks, Saul, and best of luck at the Latin Grammys.”

The Cuarteto Latinoamericano and Jaramar's Latin Grammy speaks volumes about the quality of “El Hilo Invisible.” The songs are by nature songs of exile, of people searching for home, wherever they might find it. This resonates with our own troubled times. Yet the songs on the album also offer hope for the world's displaced, that they too may one day give thanks for the generosity of humankind, for shelter where before there was only despair.

The songs of “El Hilo Invisible” are also about love:

“The first time I saw your eyes I fell in love with you.” And understated humor: “I fell in love during night, the moon deceived me If it were day, I would not have found love. If I fall in love ever again, I'll do it in daylight.”

There is a soulful mood about “El Hilo Invisible” which evokes within me a nostalgia for other times, other places. I am reminded of a night in a Spanish garden, in Seville, making music of Copland and Falla with the Cuarteto Latinoamericano. As the music resonated from the ensemble Solistas de Mexico, we were all musical friends, the moon rose over the walls of the garden, flooding the space with an indescribable mysticism. I give my own thanks for an experience which I will never forget. Thank you, Mexico, for bringing us all together through the voice of music.

Watch the official video of "La Rosa Enflorece" from the album "El Hilo Invisible" below.